Surveillance modes and technologies inform how we see ourselves, how we behave, and how we see others. Its ubiquity has penetrated the making of contemporary society, with these methods making us visible and visualised subjects. With this emphasis on rendering people visible, there is also resistance and manipulation of these methods in an attempt to reclaim a sense of anonymity and autonomy. The show How To Disappear , currently showing at Goodman Gallery thinks through the concealed and overt practices that inform surveillance and forms of resistance related to this.

Nolan Dennis Oswald, Aporia II (2016)

The show considers the layered categories of surveillance that are at play- often all at once. From racial profiling, to aerial surveillance, to the strategic accumulation of digital data based on our online activities. The write up for the show mentions the term ‘surveillance capitalism’ coined by author Shoshana Zuboff; a descriptor for the mutant form of capitalism we are experiencing that uses algorithmic data mining from the online services we use, allowing for data versions of ourselves to be created and become part of the advanced manufacturing process of behavioural prediction.

Kahlil Joseph, BLKNWS (2018)

Curator for the show, Amy Watson, explains that the title for the show emerged while contemplating the variety of works that constitute the exhibition. The speculative work Incognito (2018) by Ewa Nowak, falls into a form of resistance by presenting a device to be used to protect individuals from facial recognition software used for security cameras. This sculptural mask is presented as a potential form of commonly worn jewellery for the future. mounir fatmi’s Black Screen – The Rectangle (2004 – 2020) connects to Nowak’s work in that it is made of VHS tapes; the obsolete plastic archives of camera surveillance.

“This disappearing medium and the thought that the material recorded might be inaccessible signals the impossibility of containing evidence. The fact that this analogue material is subject to degradation and decay, which adds to this inaccessibility, is important in terms of thinking through some of the central tenants of the exhibition. The surveillance footage taken of citizens remains largely inaccessible; the very subjects of the footage hardly ever see themselves from the vantage point of the surveillance camera,” Watson explains.

Ewa Nowak, Icognito (2018)

Watson also shares that the painter Mary Wafer shared a book with her that “was formative for her [Mary] while growing up titled How To Be A Spy. Thinking about this book in relation to the exhibition, the idea of a manual — a how to guide of the present — felt deeply resonant.” Wafer’s research-based paintings depict the deteriorated facade of John Vorster Square (now Johannesburg Central Police Station), with her painting method obscuring the building, pointing to the systemic and institutionalised violence and intimidation still at play in South Africa. Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS (2018 – ongoing) speaks to the lived experience of Black people, and directs one’s attention to ideas around new forms of “new forms of restoration, retreat and resistance”. While informed by the US context, it is an important work to show in South Africa with parallel silencing, violence and profiling present in South Africa, making link between Joseph and Wafer’s work. This form of threading together considerations of surveillance and hyper-visibility globally, while still making reference to specific local contexts is present throughout the show. Ja’Tovia Gary’s An Ecstatic Experience (2015), similar to BLKNWS, points to the experiences of Black American people, highlighting the shared experiences of past and ongoing violence and triumphs that can also be seen reflected in South Africa. Nolan Oswald Dennis‘s work Aporia (2016), pillars of light wrapped in grey utility blankets offer his thinking on the interim state experienced during cycles of political contestation – moments of pause, liminality and sometimes attempts at concealment.

Jeremy Wafer, Nhlube (left) Spitzkop (right)

The show also presents share ideas and technology of surveillance over time, and their connection to socio-political circumstances. Reflecting on this, Watson draws on the spatiotemporal map at present through curatorial intervention in the show:

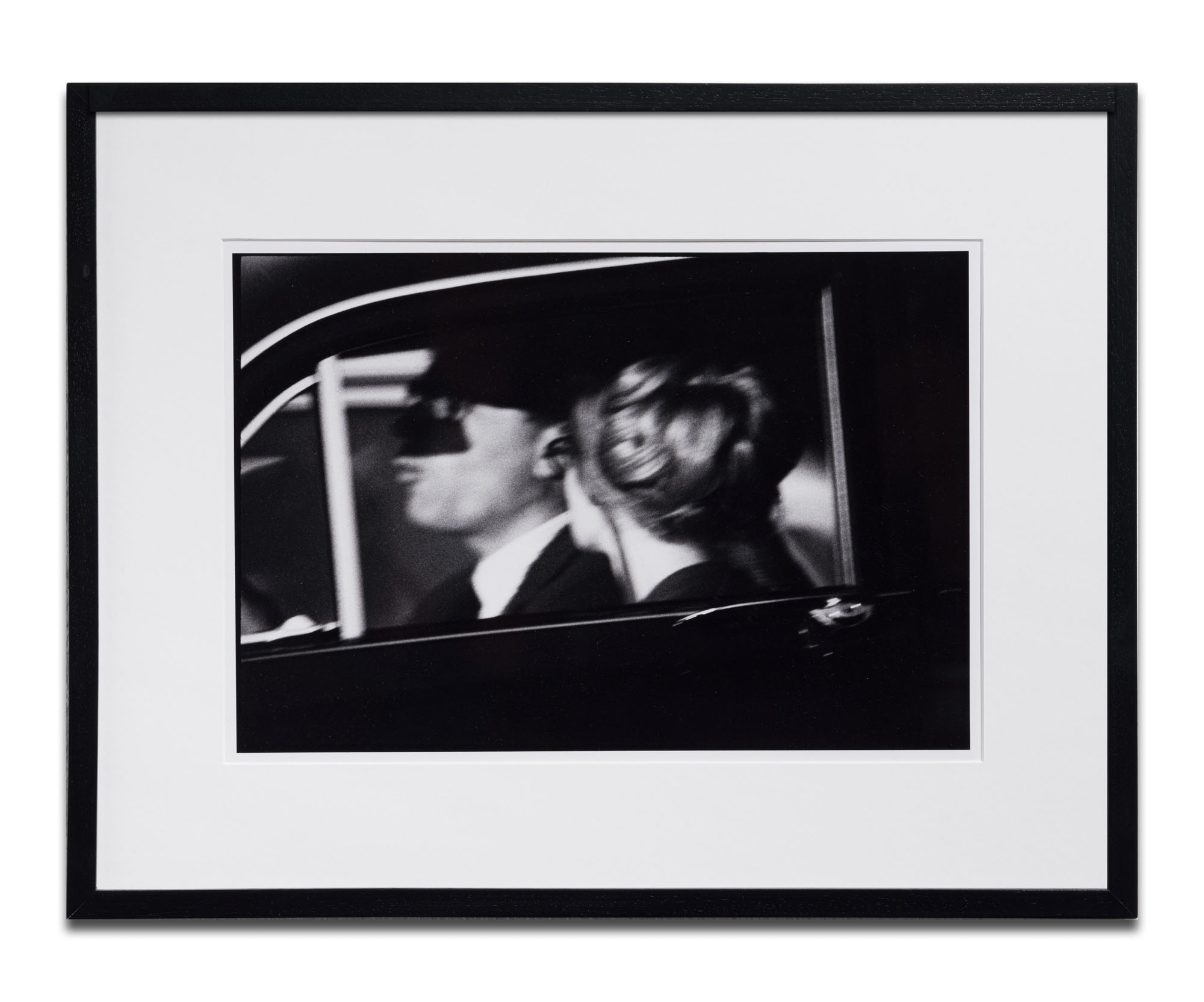

Jeremy Wafer’s ongoing use of aerial photography felt like an important inclusion: a remote, distanced looking that might be mistaken as a neutral eye. Aerial surveillance footage wasn’t always as accessible as it is today. Wafer’s images were ordered from the survey office and were initially taken on analogue medium format camera. Wafer selected the images, ‘Nhlube’, a deeply familiar space to the artist who grew up on farming land in KwaZulu-Nataland ‘Spitzkop’, a site he has never visited. These works consider how these seemingly rational languages used to map and describe place inevitably connects to the affective, to lived experience, to history and geography and one’s connection to these. David Goldblatt’s little know series ‘While In Traffic, Johannesburg’ sees a very different modality of image making for Goldblatt, one that is far more improvised and cinematic. These grainy voyeuristic 35 mm photographs capture subjects in private moments of transit where they are unaware of being imaged and of the photographer’s presence. What might have prompted Goldblatt to produce this series? A cursory online search of the year they were taken, 1967, provides some interesting context: John Vorster was the prime minister; The African National Congress and the Zimbabwe African People’s Union formed an alliance for armed struggle against South Africa and Rhodesia; The Terrorism Act, 1967 is passed; military conscription becomes compulsory for all white men in South Africa over the age of 16; the South African Police officially disclose that SAP counter-insurgency units are deployed in Rhodesia to counter Umkhonto we Sizwe and Professor Christiaan Barnard carries out the world’s first heart transplant at Groote Schuur Hospital.

David Goldblatt, While in traffic. Johannesburg (1967)

Goldblatt’s ‘While In Traffic, Johannesburg’ is exhibited opposite Broomberg and Chanarin’s ‘Spirit is a Bone’, an installation of disembodied facial renderings of Moscow citizens realised by technology employed in public security and border control surveillance. The portraits are best best described as digital life masks and are taken by a machine, and subsequently stitched together to create a likeness of a subject. As Broomberg and Chanarin succinctly state: “the success of these images is determined by how precisely this machine can identify its subject: the characteristics of the nose, the eyes, the chin, and how these intersect. Nevertheless they cannot help being portraits of individuals, struggling and often failing to negotiate a civil contract with state power.” Broomberg and Chanarin have printed these images onto a luminous reflective photographic substrate and embedded onto apertures of clear glass on the reverse of highly reflective black glass. The result is one in which audiences see their own faces reflected and cant help but negotiate their own features while negotiating the images. By contrast, mounir fatmi’s ‘Black Screens – Rectangular’ absorbs light and the obsolete 529 VHS tapes used in the work refuse viewers through the white ocular inserts of the reel cogs.

There is a tension in the idea of disappearance of course. On the one hand it refers to evading surveillance and the forms of resistance to surveillance. On the other hand, surveillant regimes have the power to ‘disappear’ people: to effectively eliminate people from the public sphere through means such as house arrest and extrajudicial executions – all of which are part of our past in South Africa and are practices which continue in authoritarian countries to this day.