I believe that art has two incredible capacities—that of stagnation and that of giving movement. I could argue more about it, give explanations through sculpture or compare Renaissance art to expressionist or abstract art. That would, in essence support the theory of my opening thoughts. It turns out that when talking about contemporary art, these concepts get a little cloudy. It’s hard to talk about it without thinking about a move backward. Today’s art has a much greater connection with the artist. They become part of the work and often the work becomes autobiographical, perhaps, even static at first sight because of the means of manifestation through painting or drawing—the movement behind the works; in history and in construction, marked with definitive clarity. When seeing a photograph or a painting let’s say, it is difficult to detangle it from the moment in which it was creatively drawn, planned, or even the fruit of spontaneity which may have led to its creation. Hence, the so-called artistic vision. However, I feel that there is another element to artistic creation that isn’t really taught at art schools or academies; that of the sensitive gaze. The ability of an artist to capture sensitively, intimately and transform that into composition or portrait. This characteristic of tender affective beauty, spreads through manifestations in literature, poetry, painting and music. Perhaps, beauty is not what is portrayed, but the capacity to portray beauty is. In detail, in layers, in a thousandth of a second in a photograph or in a set of notes in a song.

We all keep it in a certain way and express it in another, the incredible ability to see not through the eyes but through the senses. When you see Pegge‘s work, it’s clear how art doesn’t just pass through the eyes but can also pass like a soft breeze or unruly storm through various senses directing us to places known or unknown. ”Child prodigy raised without [a] father” forms part of Pegge’s Instagram bio, only this is a very short biography for the whole story that the artist carries, a complicated one of loss—at a very young age—of his father. Of battling through an illness that caused him to lose his sight and have to learn to see again, not only as a sense but also as a way reviewing the facts of the world. “If you can look, see. If you can see, notice”, as José Saramago, portrayed in The Essay on Blindness, the difference between the words see and look, fits very well into the artist’s autobiographical work exposing a vision far beyond the superficial. When I started the interview I asked Pegge who he was, how old he was and why he started drawing. He told me that his name is Pedro and that he turned 23 that year, “and that’s what it’s about!” He answered when I revealed my own age.

Having only completed primary schools, Pegge has done a bit of everything, to working as a waiter, in a bakery and even playing music in the street. In 2017, he took part in a Graffiti workshop in his neighbourhood in the east zone of São Paulo which is when he realised that he could really live off of art. In 2018, he decided to start painting. All he had was an old canvas (already painted), his sister’s make-up brush, and school gouache paint and using all this, he did. Pegge began to draw people’s attention creating contacts and in his first year, he already held his first solo exhibition. In 2019 he held another solo show called EPHEMERAL at Galeria A7MA, in São Paulo, and it was there that he really placed his feet solidly in the world of art, creating contact with his audience beyond the social media. In a conversation with me for Bubblegum Club, the artist answered some questions about his visual and musical artistic work, beyond his way of seeing the world and representing Brazilian youth.

What you portray in your works has a great power with regards to the daily existence of young Brazilians relegated to the periphery of society. I would say, in a more elaborate way, that your artistic form and production go beyond and arrives at a portrait of an extensive class of contemporary Brazilian society. Where does this inspiration come from that is so faithful and trustworthy?

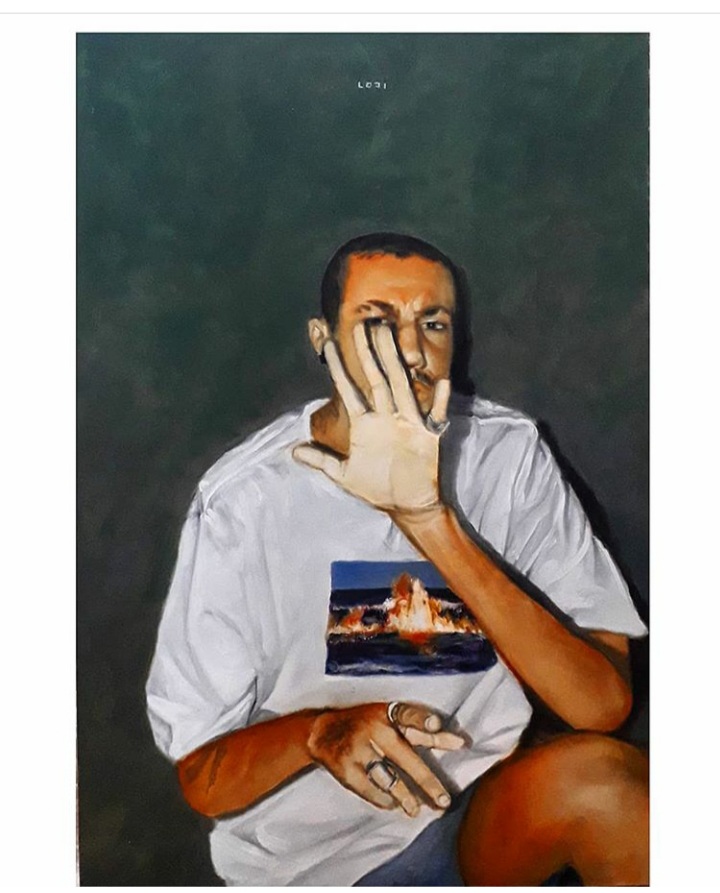

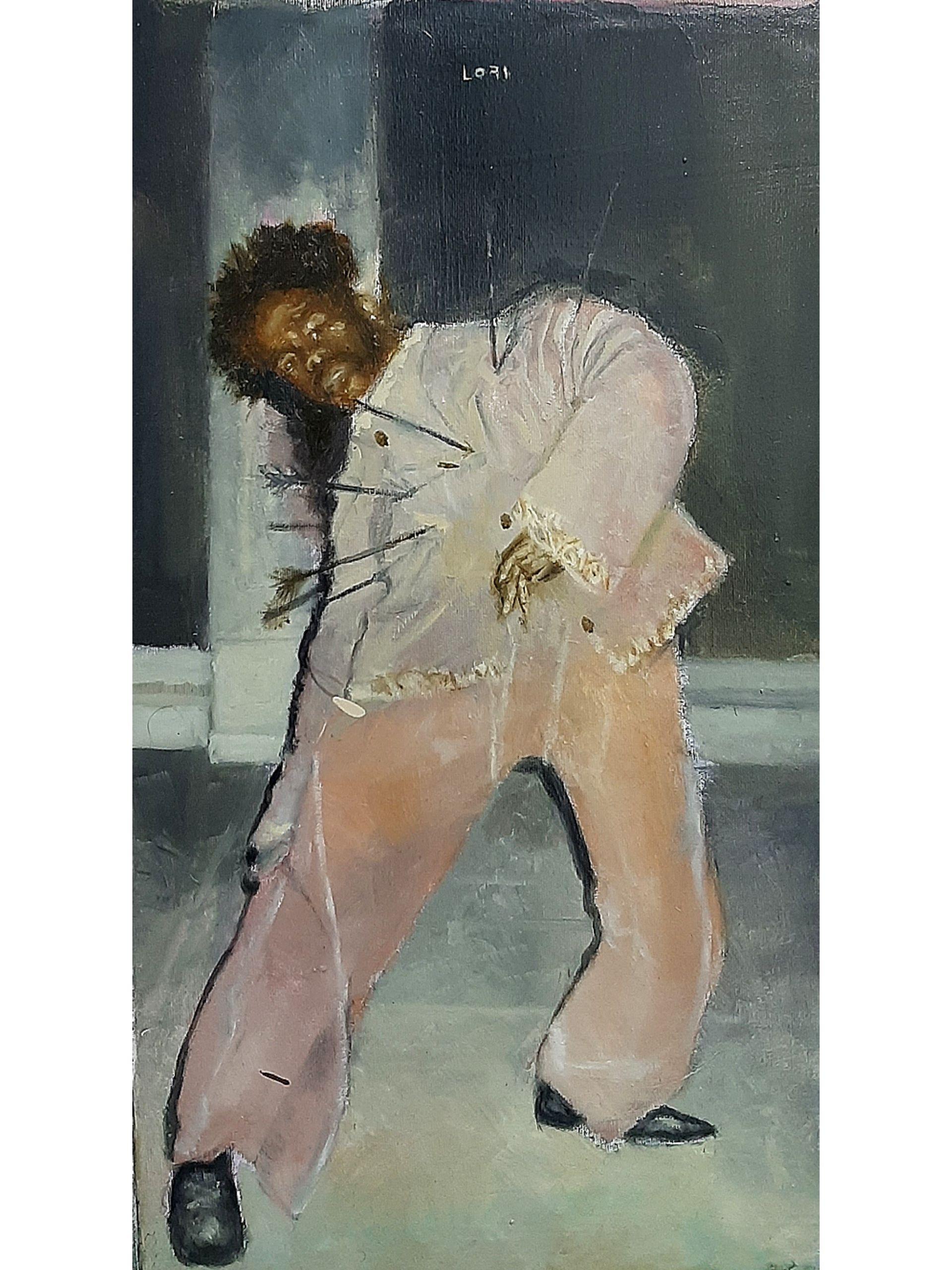

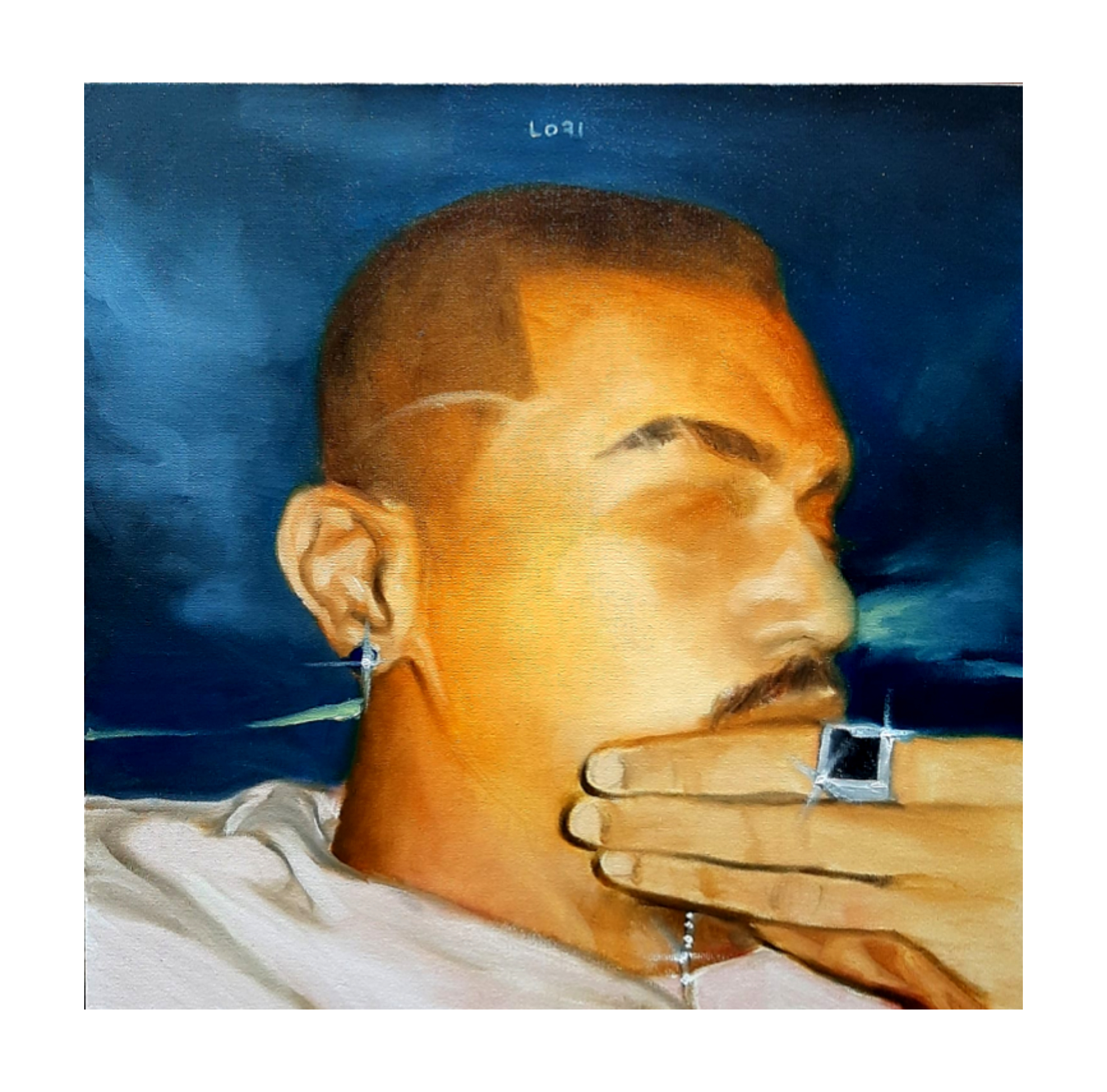

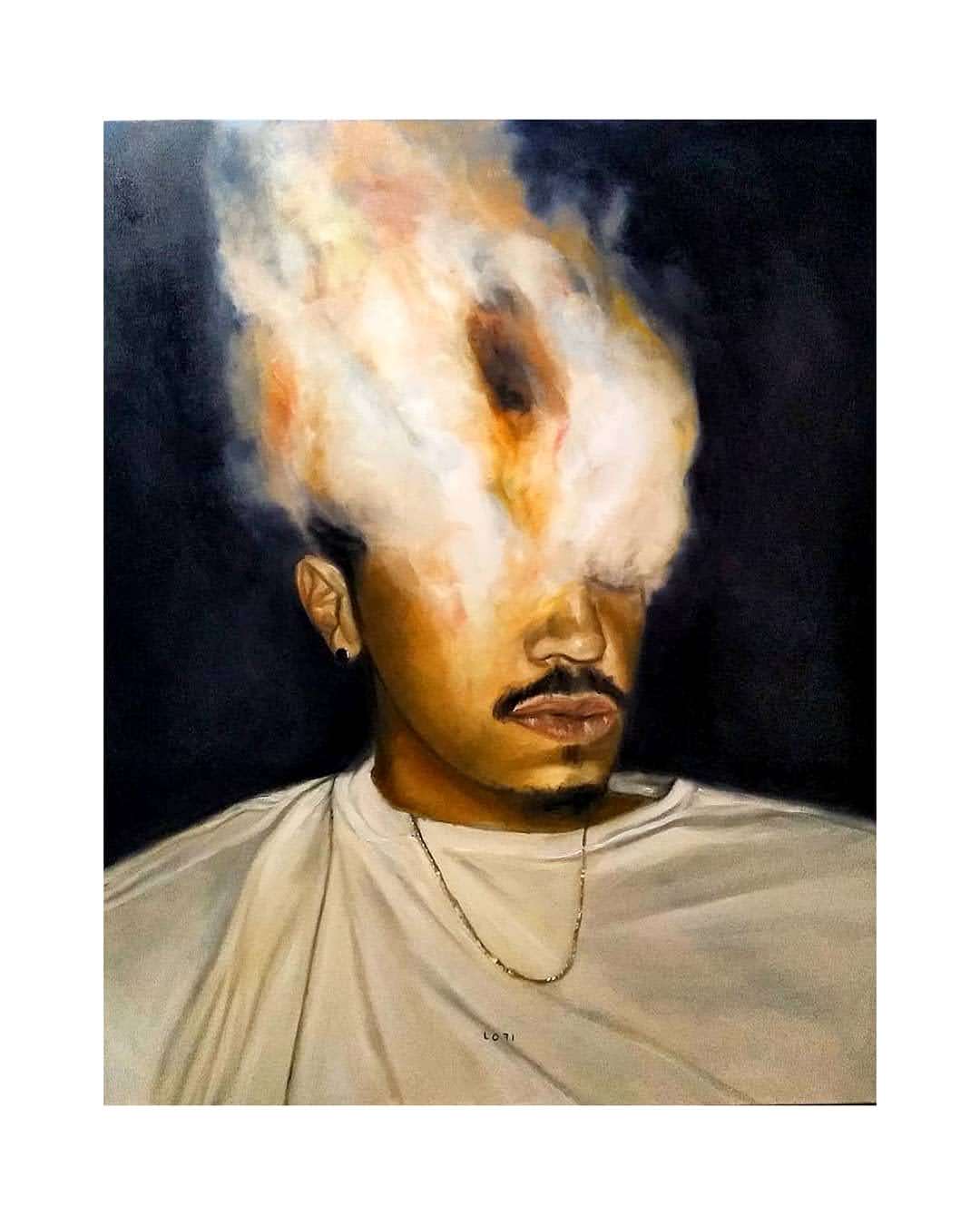

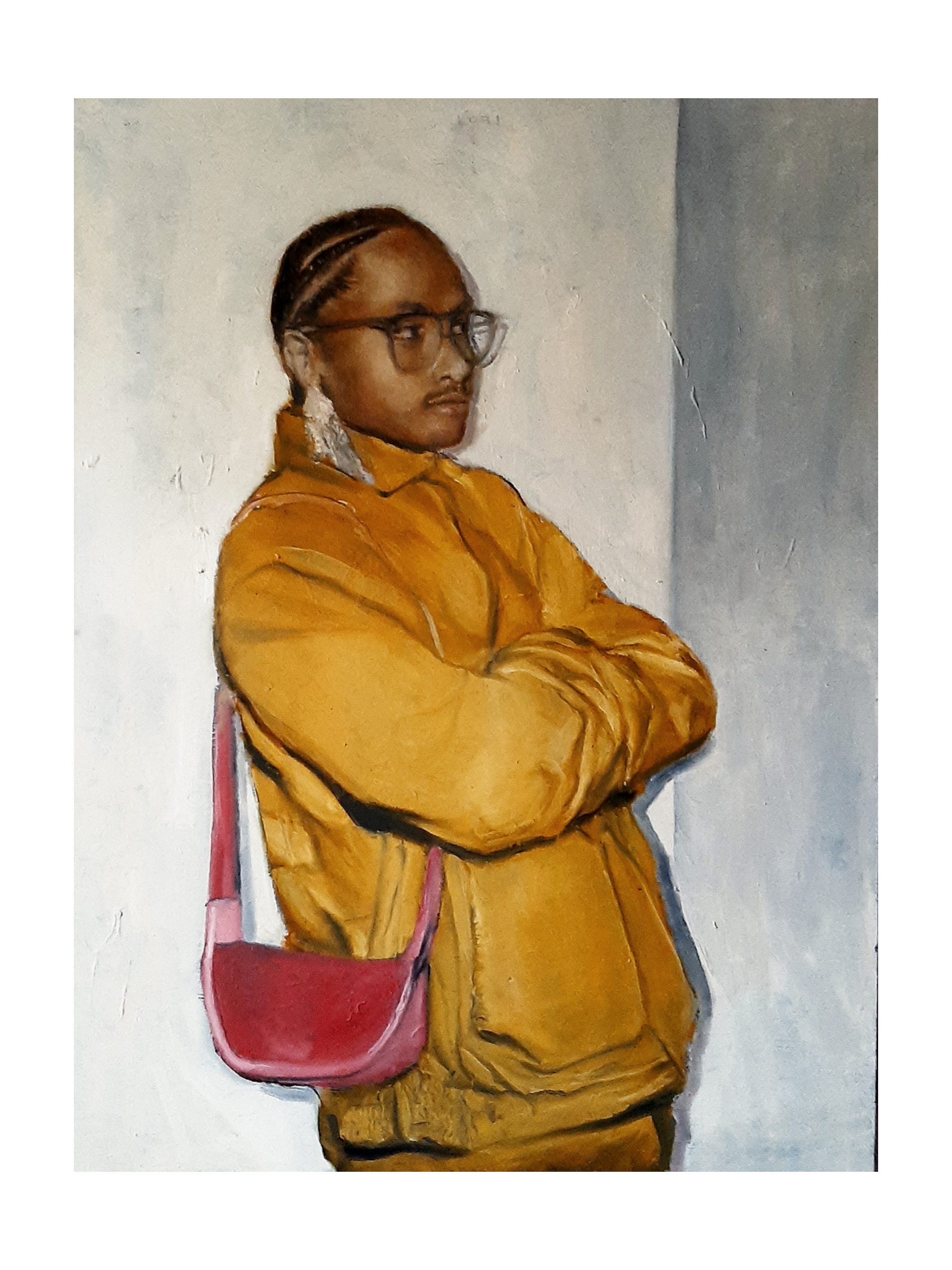

It is a totally autobiographical work. I can’t paint anything that I don’t already feel or have felt. So, there is a big question of self-portrait. I see myself in someone else and that person sees himself in me. I am a channel, I see all this work as a channel of communication. When you discover this weight—that other people read what you put on, that they see the screen and get emotional—you see the importance of this and then you make yourself ready to be that channel. You make yourself ready to talk about the feeling of being a young black man. That is never spoken, on the internet you can speak and nobody knows who is speaking, but at least someone is reading.This importance moves, to have a means of communication with those who need it.

The titles of their works—together with the works themselves—have a very strong leaning towards realism. The use of light and shadow is used as a flash. Works like Quando você vê o bb no baile or Tá pensando nela não né?, bring a load of knowledge and dialogue about the daily life of these young people. In the first layer, their work is visual and their titles bring a second layer, probing even deeper. Where does the connection between the work and the title come from?

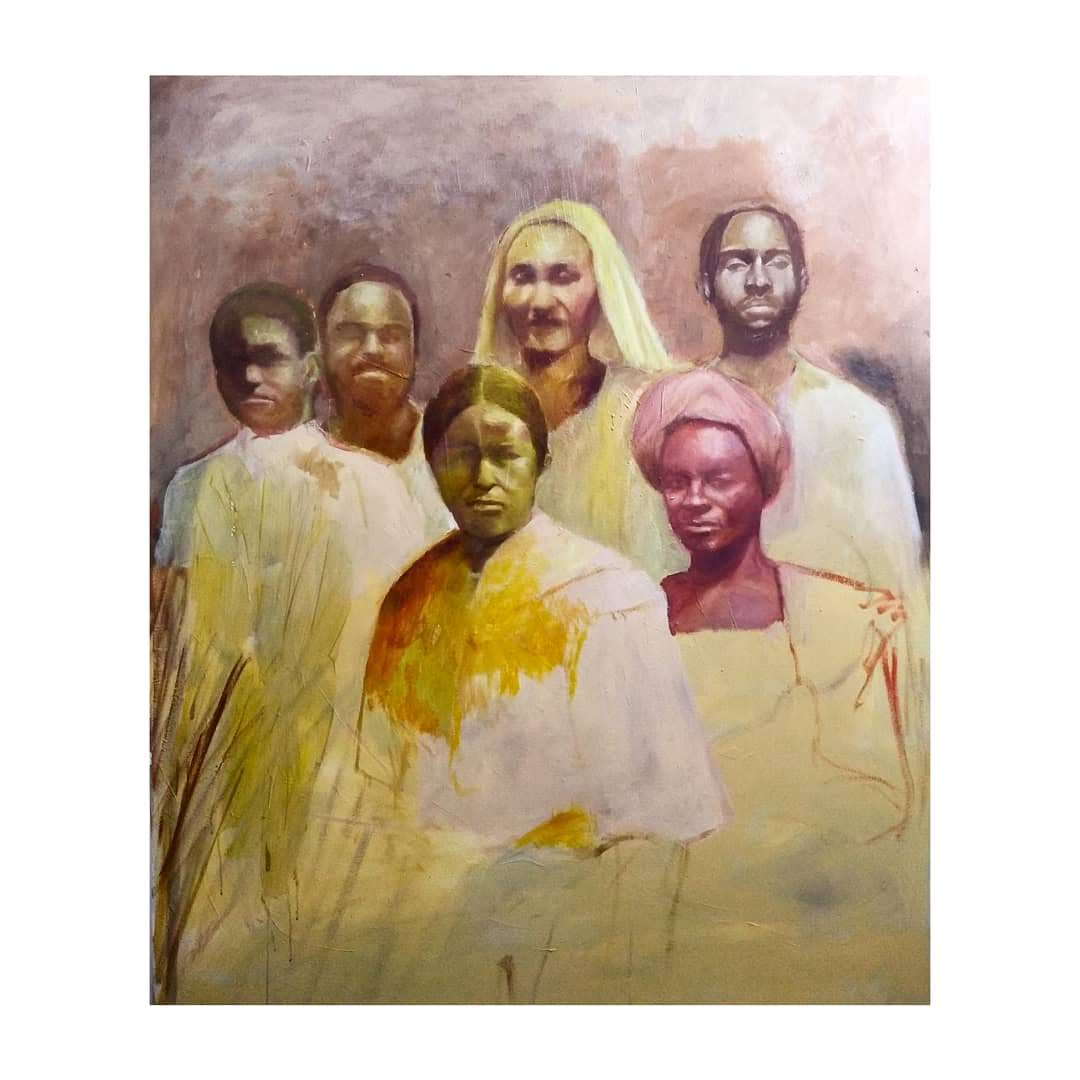

I think a lot about titles! It’s very important, it’s the doorway to the work. In the case of Instagram, you see the work first and then you see the title, but it has to be something that makes you read the rest. I have this work for SP Arte, which had originally been made in 2019, is still not finished and never will be even though it is on Instagram. On Instagram, she has no title, because I didn’t even know what to call her, however, to exhibit it I needed to give it a name and I thought of several things. The work [engages with] the black genocide, which happened in the past and is still happening. I saw how it affected me in various ways. So, it is composed as if it were of a jury with only black people. Bringing up the question that if this was a jury that a racist person was going to be tried by, would he or she be afraid of being recognised as racist [in front of this all black jury]? Because today I they [wouldn’t be]. Thinking of a name for it was very intense, until I arrived at White Skin, Red Hands, what kills gets red hands and so the trial. I think that was the most striking title I could have given and today I understand much more about the importance of thinking more and more about it. Tiles can be like a second doorway to another thought that will take you someplace else—I want to pave a way for interpretation.

Do you play instruments? Are you a musician too?

I play! Yes, I do. My first instrument was a cavaquinho, I got it from a family friend and it was huge for me! When I was 13, I wanted to learn to play the guitar, a friend lent me his and I took some lessons but I didn’t like it. I really like to learn by myself and when there are methods I find it a bit boring. In time I learned and then I went back to the cavaquinho because it’s almost the same metric and so it was with the keyboard, bass, and drums. The most recent [instrument] I’ve learned is trumpet, maybe before the end of the year I will release an album too. I already have about four songs, all instrumental. Music has always been part of it. I think I like music more than painting—sometimes I contradict myself—but I think music is the most complete art. You put memories in the music, moments; it holds sensations. Art and canvas are very private, you have to have the internet to see my work. One thing I’ve been questioning a lot in my work is how to make it public.