We have all seen the social media posts of celebrities draped in designer clothing from head to toe while simply running their daily errands, in awe of the sheer opulence of it all.

We have dreamt about owning and experiencing garments and grails that serve their purpose not only through their prime function – as a piece of clothing or accessory – but also arguably playing an even more significant role of visually showcasing a level of status and wealth.

We have all seen an acquaintance celebrate finally winning that sneaker raffle and getting a chance to purchase those Jordan 1’s they haven’t been able to shut up about since Shelflife and Lemkus posted details on Instagram.

We have also all seen the blonde bombshell styled like she’s straight from the set of Euphoria – clutching her Louis Vuitton bag in dingy bars where the bathrooms look like you could pick up an infection just from being in there for too long.

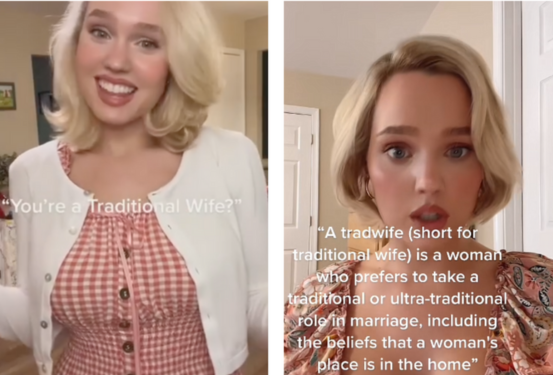

A constant barrage of fashion shows, lookbooks and influencers establishing new trends and throwing away last season’s to the wayside, has undoubtedly made us far more brand conscious than before. “Bieber is the new face of Balenciaga”, plastered all over our timelines thousands of times simply has to have some psychological effect on us.

There’s this specific type of envy and desire that accompanies the sheer amount of branded material we are exposed to online, this sense of high capitalist consumerism controlling our spending habits through masterful, albeit ethically questionable, marketing ploys. A sense that your self worth and social status is solely determined by the things you own.

So what do we do? We go online and look to buy these items, not necessarily because we need them but because we convince ourselves that things would be better if we did. Unfortunately for most of us, that is where reality sets in; when we realise the aforementioned Balenciaga is asking $450 (approximately R6 750) for a plain white tee with their name printed on and $615 (approximately R9 200) for a boxy pre-distressed tee.

Now of course there aren’t many people able and willing to pay that kind of money on clothes, let alone a single t-shirt. So as consumers, we basically have two options: either don’t purchase the item because we can’t afford it, or the most likely option of looking for alternatives online (whether they are counterfeits or ethical).

I think most, if not all, of us have at some point in our lives indulged in counterfeit or pirated goods, whether it be a flimsy pair of Ray-Bans from the hawker at a busy robot, fake pairs of Yeezy’s bought for a semblance of clout, or that little LV bag that looks great in pictures but is basically falling apart at the seams.

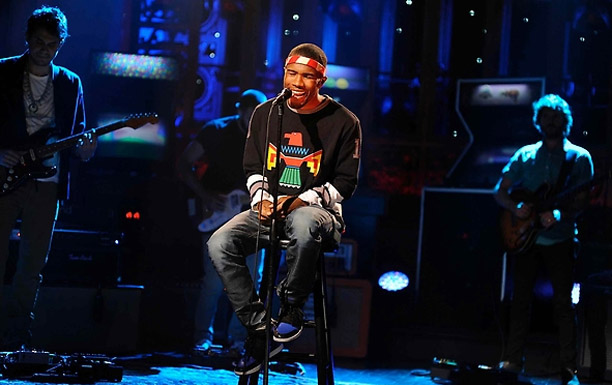

In my case, it was the height of Supreme mania (we all make questionable decisions), and I had recently rewatched Frank Ocean’s SNL live performances and desperately needed that Supreme Thunderbird Hockey Jersey he wore on the show. I scoured the net, trying to find anywhere I could get a hold of it, just to be hit with a cool $1 000 price tag on Grailed (there is also currently a single listing for $4 500 if anyone is interested).

As a very broke university student, I did what I had to do and found a knockoff on some ridiculously dodgy Chinese website. In all fairness, the item which arrived had way better quality than what I had expected but still only lasted four months before it was in absolute tatters.

Now I want to state that I actually don’t have that much sympathy for these giant corporations and the manner in which the counterfeit market affects their profits, as despite an endless amount of fake Louis Vuitton being produced, the LMVH group still managed to turn a net profit of €12.7 billion in 2021 – which was up significantly from their pre-pandemic figures. Let’s be realistic, most people on a continent as impoverished as Africa can’t even afford branded items such as Nike and Adidas, let alone luxury designer brands.

Still, a lack of funds doesn’t necessarily curb the sheer demand for these goods, and there is undoubtedly so much to be said about where these counterfeit goods are manufactured and how ethical these conditions are. More so, there is also a lot to be said about the environmental impact of fashion as a whole – which is further exacerbated by the fast fashion industry.

In truth, South Africa is an ideal location for counterfeit goods to land. It has a rapidly growing middle class that is looking to cement their newfound economic status; it provides easy access due to its multitude of ports and can serve as somewhat of a distribution centre to get these counterfeit products into the rest of the continent.

Let’s not beat around the bush – there’s a lot of counterfeit goods in South Africa. Just last year, Johannesburg police confiscated and destroyed R24.5 million worth of fake goods within a single raid. And still, the rate at which counterfeit goods are entering SA is far too high as of 2011, over a decade ago, the counterfeit market in South Africa alone was estimated to be worth upwards of R360 billion. I mean counterfeit goods made up 3.3% of all trading globally in 2019, and it’s only increasing.

Now as I mentioned above, I don’t blame people for buying counterfeit items, because in some way, this may be the only means for them to experience these products, even if they aren’t authentic.

I also don’t blame consumers for supporting fast fashion brands like Zara – who have rooted their whole business model in nabbing ideas and trends from designers and repackaging them as a more affordable product (although Zara is still overpriced in my opinion).

Similarly, we’ve seen the likes of Mr Price do the same in recent years, bringing out budget versions of Balenciaga’s polarising and popular Triple S sneaker, a recent take on a boot by Bottega Veneta and most notably, due to the sheer amount of memes online, their own Yeezy slide.

I do however have massive concerns with how the local counterfeit market has the potential to impact and exploit not only South Africa’s small fashion market but also its consumers.

For example, the issue of fake sneaker resellers on Instagram is so bad that Shelflife even run a whole Fake Friday segment – exposing a bunch of these pages and their immoral business practices. Unfortunately, the exploitation of customers isn’t limited to just fake sneakers, as we’ve all probably come across a multitude of online thrift stores which follow suit.

Now fortunately, items from luxury brands such as Balenciaga aren’t the hardest to authenticate, and yes, buyers should be doing their homework, but surely there is an ethical responsibility as the seller to make sure what you are selling the real thing, or alternatively pricing it down as a knockoff piece.

I respect that people are just trying to secure the bag, but if that comes at someone else’s expense, that is exploitative, simple as that.

My other gripe isn’t necessarily with the counterfeit market but rather the liberties big corporations take in nabbing ideas from smaller businesses. Famously South African designer Laduma Ngxokolo, the man behind the MaXhosa brand, took Zara to court after they snatched one of his sock designs.

Unfortunately, this is an all too regular occurrence within the fashion industry, as international retailers such as Woolworths have also been accused of this on multiple occasions.

However, I think the one that stands out to me most in a contemporary context is Mr Price taking some very direct inspiration from Cape Town-based jewellery brand Pina’s now-iconic daisy hoop earrings.

Over the past few years, these earrings have become almost synonymous with Cape Town and its small but thriving fashion scene. And for our local industry to sustainably grow, local retailers should be celebrating the achievements of smaller South African businesses, rather than snatching their ideas when they become popular.