George Foreman came to Africa with a German Shepard. In 1974, Foreman had been promised a record sum of 5 million USD to fight veteran boxer Muhammed Ali. The fight was being called ‘The Rumble in the Jungle’ and the venue chosen was the grand Stade du 20 in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. It was common opinion that Foreman was going to win the fight. He was younger and stronger than Ali, who was coming up on the end of his career. Foreman was the critics bet, but he wasn’t the people’s favourite. It was widely reported that he didn’t speak to locals, didn’t shake hands with people and never left his villa. His only constant companion was Levy, the German Shepard: a breed of dog used during imperialism to keep Congolese people in line.

Ali was the peoples champion. He’d been a member of the Nation of Islam and a confidante of Malcolm X. X and the Nation had long ministered the Garvey-esque idea that the black man’s real place was in Africa. Even after his fallout with X, Ali held onto this idea. He spent the 55 days leading up to the fight enjoying Kinshasa, living in a smaller hotel closer to the locals, allowing the public to watch him train. He did not bring a German Shepard. Ali even visited the Palais de la Nation to visit Mobutu Sese Seko (who was reaching the height of his military dictatorship at the time). When reporters caught Ali outside, he famously exclaimed “all my life I’ve been hearing about the white house…today I saw the black house!”. Ali, like many black American’s during the Civil Rights Era, was searching for a truth outside of US borders. The 60s had brought some victories, but many disappointments. For many, Africa existed as a land of complicated feelings. Caught somewhere between a romanticised black paradise and a jungle land doused in anti-black stereotypes and self-hatred. Still, in the diasporic mind, Africa was a place where at the very least: a black person could attain a slice of freedom.

When Nina Simone accepted a request to come to Liberia, she was chasing the same dream Africa as Muhammed Ali. Miriam Makeba was on the bill to perform at the Foreman x Ali fight of 1974. She and Simone had become acquainted through the Civil Rights Movement and anti-Apartheid struggle. Their social circles intertwined as people moved between New York, the Caribbean and the Continent. Makeba, who was at the time living in Conakry with her husband Stokely Carmichael, invited Simone to come for a visit. Struggling with America-fatigue and dealing with financial troubles, Simone packed up her daughter and other belongings and boarded a plane to Monrovia.

In an essay for The Atlantic, Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote “Simone was in possession of nearly every feature that we denigrated as children. And yet somehow she willed herself into a goddess.” In the essay, Coates touches on how much of Simone’s legacy lies in her physicality. To quote Simone’s own lyrics, her skin was black, her arms long, her hair woolly and her back strong enough to take the pain (inflicted again, and again). It was simultaneously the thing that held her back from the opportunities she wanted most and the thing that elevated her to a most high status in her era. Her physicality is also a thing that most closely connected her to Africa. 1960s America had little place for black people, much less a hot-tempered, opinionated, intelligent, successful dark-skinned black woman. Navigating the relentless minefield of disappointment and heartache borne of misogynoir and racism weighed heavy on Simone’s soul. She knew she could never be happy in America. So, she set out for places where people looked like her. Where, she imagined, these features would at least be accepted if not celebrated. In one of her diary entries she wrote “it’s bad enough to be born black in America, but to be burdened down with the problems within it is too much.”

Simone wasn’t the first of her comrades to make the pilgrimage to Africa and try to settle here. Malcolm X had seen Egypt, Nigeria and Ghana. Stokely Carmichael had married Miriam Makeba and settled in Guinea. Maya Angelou fell in love with Vusumzi Make, a freedom fighter, and moved to Egypt with him before becoming a faculty member at the University of Ghana. In fact, when Simone arrived in Liberia she joined a community not only of expatriates but of Americo-Liberians who had been living a life of privilege on African soil for generations. From the outset, Liberia presented itself as the black dream world. In the glory of the 1970s, the glaring inequality between Americo-Liberians and the indigenous Africans upon which they resettled fell to the wayside in favour of black self-discovery, repatriation and the nightlife. During her time in Liberia, Simone dated the cities elite bachelors, played for private parties and indulged in the nightlife. A local recounted to Guernica Magazine a time when Simone, flanked by the who’s who of Liberia, got into a club, undressed herself and played piano for everyone at the party. Her years in Liberia were a journey of finding herself, in a space where for once, she felt she could be at least a version of her authentic self. It was the place in which, it seems, Simone felt she could access something pure. In a radio interview from What Happened, Miss Simone, she said “I have seen lightning in Africa, it electrifies you into speechlessness… I have seen God”.

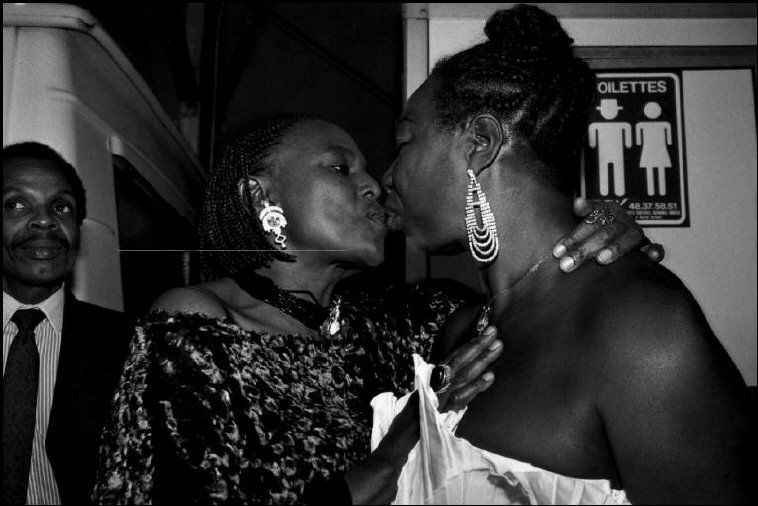

Her musical career stagnated while in Africa, as she focused on shedding the celebrity and celebrating the personal. Stagnated but did not die. During her time, she played for many private parties. One of her lesser known gems is a song called “Thulasizwe” with Miriam Makeba. The song is part Bob Dylan cover, part apartheid struggle anthem. “Thulasizwe ungabokhala/ You, Jehova wakho uzokunqobela” both women coo over the pitter patter of piano keys. Years later, in an interview with the BBC, Makeba would say, “It’s an interesting version, where I felt that we were bringing two worlds together – South Africa and the United States – both music and artists, in that Nina Simone was also singing it with me.” Makeba elaborated: “Thulasizwe is like saying, “It’s alright,” to the nation – no matter how we are struggling, God will be with us and we will make it.” In many ways, “Thulasizwe” is an anthem about a nation state. But in this case, the ever-roaming Simone is the nation state: singing to herself and to those that look like her that things will be alright. That’s the peace that she was searching for.

It’s a well-known tale that Nina Simone had no ambitions to be a jazz musician. As a child learning to play classical piano, she dreamed of playing Bach at Carnegie Hall, not the ‘race music’ for which she would become most popular. But her wooly hair and black skin kept her locked out of music school classrooms. For many reasons, many of them outside of her control, America had been unpleasant. Once she left, she never returned. Liberia, for many years, was Simone’s chosen paradise. It was on African soil that she engaged on a different plane and saw different opportunities for being black on this planet. She was able to live out the life she had dreamed in the 60s.

Unfortunately, Africa isn’t a dream. It’s a place. And as with most places, the reality never quite matches the imagined. Two years after Nina Simone left Liberia for Switzerland, political instability reared its head. Rebel groups sought revenge for decades of injustice perpetuated by Americo-Liberians. President Tolbert was murdered in a coup and 10 former ministers (including a former boyfriend of Simone’s) were publicly executed. The country has yet to fully recover. Simone’s 1970s Liberian paradise was lost, and she was unable to live out her fantasy fully. Conjointly, Apartheid only ended in 1994 and both black Americans and South Africans continue to exist at the disadvantage of structural racism and police brutality.

Legacy lives through and past people, and the story of Nina Simone in Africa stretches past Liberia and outsizes her own life. The nature of popular music is to constantly morph and re-work itself, with works of art living implicitly through everything. Simone’s music does this. When people in Monrovia are asked to recount their youths, they often speak of her. When our parents think of the songs that remind them of good times: she is there. You can hear her in Hugh Masekela, in Abdullah Ibrahim, in Yvonne Chaka Chaka and in Makeba herself. You hear her in the Orbit on Juta Street. You see her in the “young, gifted and black” tattoos that pop up on brown skin every so often. Maybe the true African paradise is that she exists freely in this space, forever.