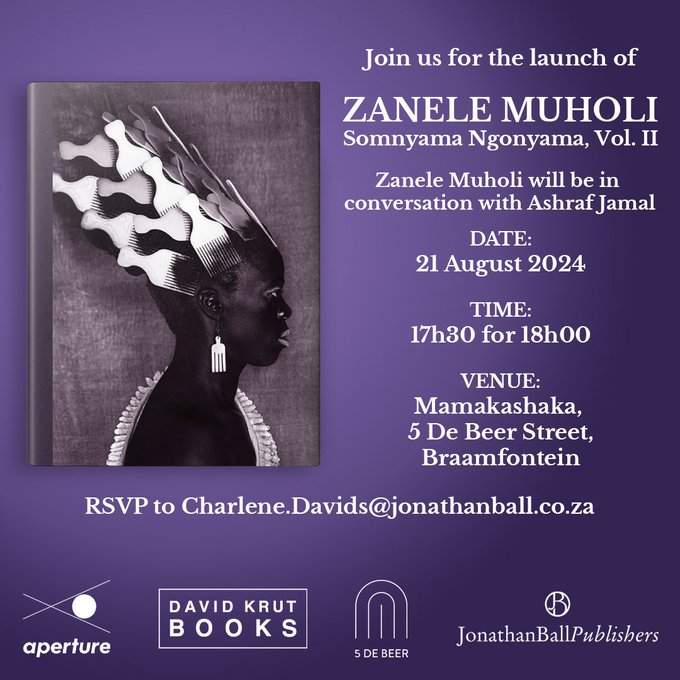

Thanks to the support of Southern Guild, David Krut Bookshop, and Jonathan Ball Publishers the event, which took place on August 21, 2024, at Mamakashaka, Braamfontein included a conversation between the famous photographer Zanele Muholi and cultural theorist Ashraf Jamal. The occasion was to launch Muholi’s Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, Volume II, which delves into Black queer identity through striking portraits and poetry, continuing to challenge perceptions and expand on themes of personhood and resistance.

As the discussion began, Jamal jumped to a question on the relationship between courage and fear. I found this an intriguing place to start as Muholi has perceivably been conquering the global art world for many years now. Their portraits have been celebrated globally, including with solos at institutions like Tate Modern and The Brooklyn Museum. But as he went on, I began to grasp what Jamal meant with his curious question. He remarked, “One can be brave, but one must also be vulnerable,” suggesting that this was a central element in Muholi’s practice.

Muholi responded, “Yeah, so when I started working on these projects, having previously photographed other people and attended various protests, prides, and other spaces, I was always excited to see Black people in those environments. I remember my first experience co-founding an organization and how striking the people I photographed were back then, and how they have evolved since. Looking at myself from then and now, I realize that the body changes over time. The face of that once-beautiful, plump lady has changed too. Between fear and vulnerability, one always contemplates the future, reflecting on how things once were. When people share their images on social media, it’s a reminder of how they have changed over time.”

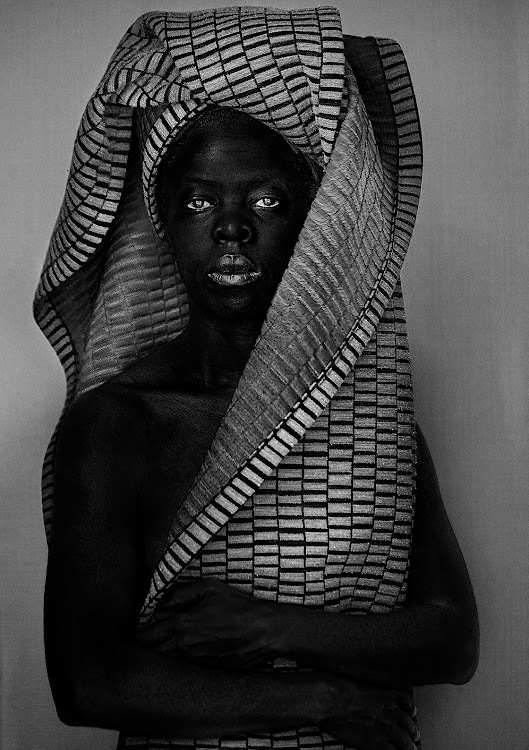

Jamal praised Muholi’s contribution to the field. If one didn’t catch it from his numerous writings, then one could tell from this interaction that he is a fan. While Muholi is a politically engaged activist, Jamal was interested in how it deviates from conventional imagery. “Muholi’s work is absolutely unique,” he declared. “While South African photography often focuses on documentary realism defined by ideology and politics, Muholi’s expression diverges from this conventional repertoire. […] The images track you down. You cannot stop looking at them because they draw you into a state of anxiety, stress, love, and passion. […] The artist has such an incredible grasp of their personal drama.”

Throughout the conversation, it was as if Jamal was trying to connect us to a more contextual reading of these famous photographs. “It’s about how the artist inhabits all these personas,” he said. What’s really important to me is that, after over 500 years of colonization and the negation of Black life—its soul, agency, and self-control—what emerges is not a classic plea for recognition. Instead, it’s a performance of complex identities that offer a deeper understanding of African life, Black experience, and the African diaspora.

“We have a beautiful visual history in South Africa,” Muholi responded modestly. We have people like you who theorize the work, but in my view, theory cannot survive or exist on its own without a visual component. […] We can theorize as much as we like, but if we […] need these visuals to articulate ourselves in new ways. By insisting on self-portraiture, we preserve a moment of self as we navigate different spaces. […] So I’m really fascinated by Blackness in many ways. I understand how uneasy it can be for others who may not like to be photographed, but for me, so far, so good. Hence, I aim to produce up to five volumes. In the second volume, more than 100 images have been edited to create this final document. I’m busy working on the third. I see this as an eternal journey.”

Thrillingly, eventually both Jamal and Muholi pointed towards the performative nature of this kind of photography. Jamal asserts, “Muholi’s work turns its transgressive and transactional value into substance.” Though I was in no mood that night to raise my hand, wait my turn and tightly try to retain my question until it was my turn to speak, I wanted to say “Mapplethorpe! Sherman!” In art, we’re blessed with so many examples of moments when artists turn the camera on themselves and perform different subjectivities.

Muholi’s photographic practice challenges traditional narratives, affirms Black queer resilience, and this conversation between the artist and the ever eloquent Ashraf Jamal was an easy reminder of that fact. Queer Africans navigate subjectivity in a myriad of ways and with varying constraints and results. But it has never been clearer that visual arts and digital media are vital tools in these endeavors. Muholi’s Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, Volume II epitomizes this process and redefines Black queer experiences through simultaneously familiar and bizarre self-portraits.

Buy the book here.