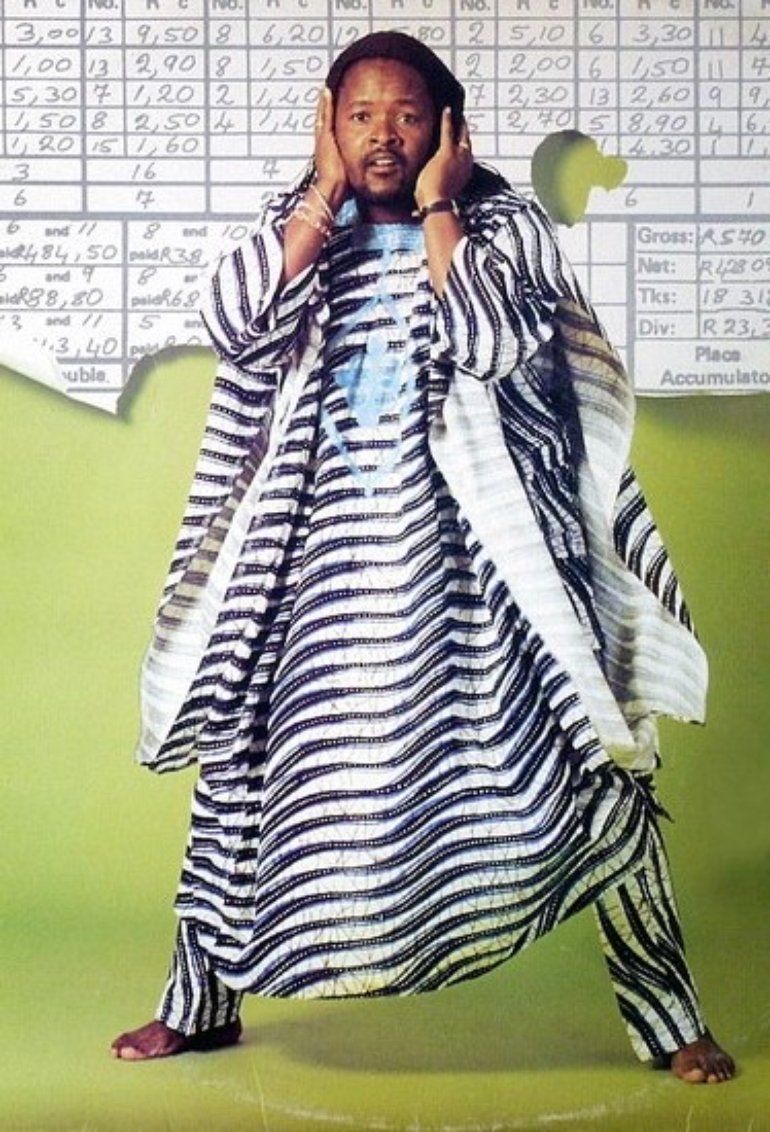

While Condry Ziqubu’s rise as a star of South Africa’s ‘bubblegum’ disco era may have appeared rapid, before his big break as a solo artist in 1983, Ziqubu had already been working professionally in the music industry for 15 years. A regular on the local soul scene since the late 1960s in groups such as The Flaming Souls, The Anchors and The Flaming Ghettoes, by the mid 80s Condry Ziqubu had qualified as a sangoma, recorded with Harari—the biggest group in the country at the time—fronted his own group Lumumba and travelled the world as part of Caiphus Semenya and Letta Mbulu’s band. Now, while the names of Mbulu and Semenya still live widely in contemporary conversations about genealogies of South African music, and while their songs such as “There is Music in the Air”, “Not Yet Uhuru”, “Ziph’inkomo” and “Nomalanga” to name but a few, still reverberate through radio stations and playlists alike—the name of Condry Ziqubu is heard far less than those of his contemporaries. This even though the artist also contributed to the country’s ‘bubblegum’ disco era in his own distinct and immeasurable way:

Born on 28 July 1951, [Condry Ziqubu] cut his teeth with two seminal bands of South Africa’s nascent soul scene in the cultural hub of Alexandra in northern Johannesburg – performing regularly and getting his first taste of recording. By 1969, aged 18, he was sharing songwriting credits on most of the songs of The Flaming Souls’ album ‘Alex Soul Menu’, also playing rhythm guitar on The Anchors’ Soul Upstairs.

For some of us—perhaps even many of us Black children of the so called post-apartheid/post-TRC generation—the textures and notes of this particular sound and the stories woven into its melodies are firmly anchored in memories our growing up years. Memories of loud, happy gatherings in the form of Sunday braais; parents talking things past and dreaming up those to come in riddles the children can’t comprehend, skin shrivelled course from too much time spent playing in the pool, chakalaka and newly free(er) Black middle class aspirations meeting Black Joy under sweet jacaranda clouds, spying from the corner of your little eye malume so and so stumbling during his solo dance in the lounge somewhere in-between Abdullah Ibrahim’s “Mannenberg Revisited” and Bra Hugh Masekela’s “Chileshe”.

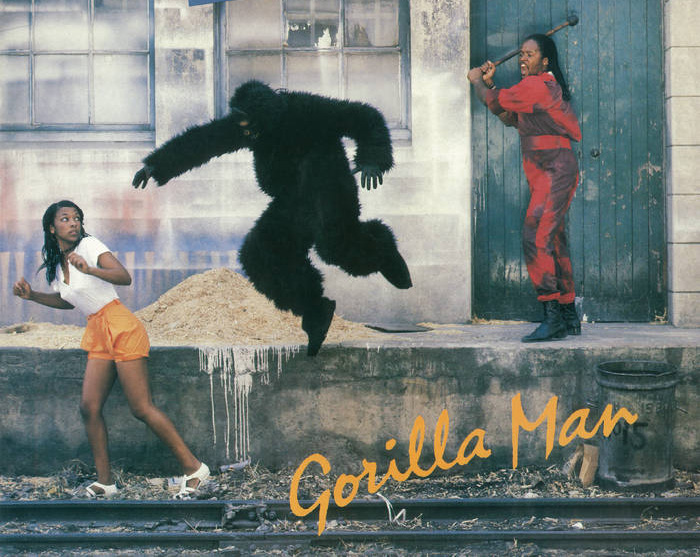

In February of this year, Afrosynth a record label who also have a retail shop specialising in kwaito and bubblegum pop music on vinyl, will be serving up a four track offering by Condry Ziqubu comprised of material originally released between 1986 and 1989. “Gorilla Man”—which was Ziqubu’s first solo hit—makes up part of the sonic anthology. The song opens with an audacious 20 second intro, telling the story of a man who preys on women in downtown Joburg and highlights Condry’s swimming formula of lyrics that touched on daily issues and places, without being preoccupied with apartheid censorship. Also included on this new anthology is another song, the politically charged “Confusion (Ma Afrika)”, as well as “Phola Baby” from his 1988 album; Pick Six which addresses gender-based violence. “Everybody Party” from 1989’s Magic Man, a through and through get-down song with no political or social intimations—other than as a brief escape from the harsh reality of the time—also finds its way into the music anthology. Although not all of Ziqubu’s discography focuses explicitly on the socio-political and economic conditions of his time, as a working and mobile artist within the apartheid state of South Africa, he could not escape the clutches of surveillance and racial oppression. As one of the few local musicians who travelled frequently and returned home to the country—Condry’s movements came under close scrutiny from apartheid officials. Scrutiny which including having his passport confiscated and persistent interrogations and harassment from the police who were convinced that his travels in Africa were as an agent of the then banned African National Congress (ANC) rather than as an artist:

It was difficult, because when we came back [into SA], we had problems. For example, police came to my house, they’d been monitoring my [movement] in and out of the country. They thought I was working underground for the ANC, so I was arrested… We used to travel at night, most of the shows we were doing at night. You’d meet South African police on the road. White police would stop you. ‘Hey, where you going?’ They’d just harass you for nothing, for sweet nothing.

Despite the cultural boycott placed on South Africa and the numerous other obstacles preventing South African artists from succeeding on the world stage, his earlier experiences with Harari, Belafonte, Semenya and Mbulu had taught him not to lose hope. This article alone is not enough to quantify or speak to the lasting and overarching cultural and sonic influence Condry Ziqubu has had not only in South Africa but the world over, despite him not being as popular as his contemporaries in the mainstream. The tributaries of his influence flow still into our music, culture and memories.

Gorilla Man will be released on vinyl and digitally in February 2021 on Johannesburg-based Afrosynth Records, distributed worldwide by Rush Hour in Amsterdam.

Pre-order link: https://www.rushhour.nl/