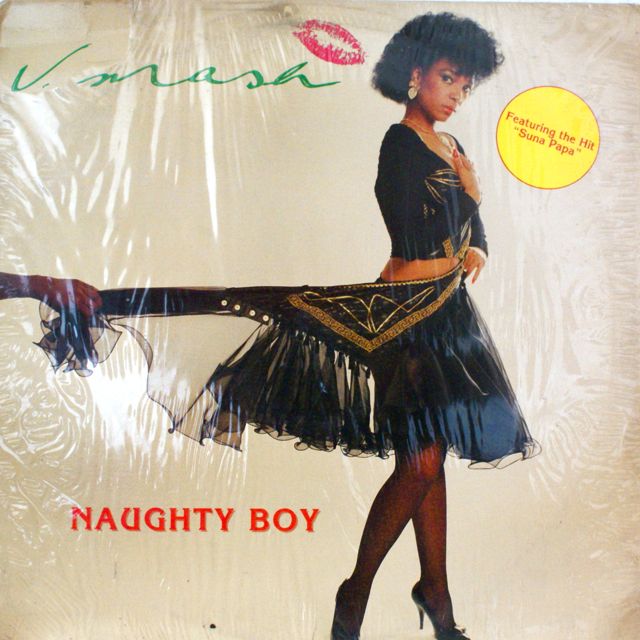

The text that is to follow is an exercise of sorts between writer Kneo Mokgopa and myself. An attempt at writing together from afar and from places of familiar difference, of Vinolia Mashego, who was affectionally known as V Mash to us and the rest of the nation.

To write of her in remembrance and lament, with our words, with our opaque childhood memories and with our unbridled youthful joy that couldn’t comprehend then, the full spectrum of what she represented and would continue to symbolise, as we shouted “obviooooousssss” necks stretched in excited anticipation towards our respective television sets, in our different childhood daydreams.

The italicised parts are the thoughts and words of Kneo, and those which are not are mine, woven in a ritual of affectionate and critical remembrance next to theirs.

…

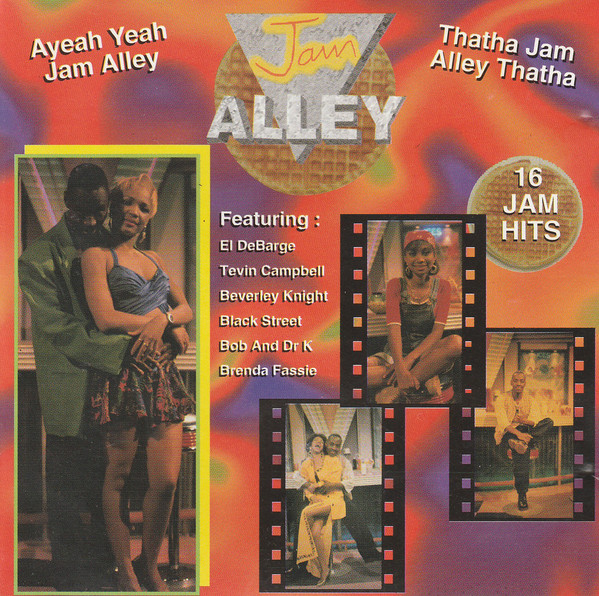

Jam Alley was a family ritual in my home. We lived in Credi, Katlehong, and all huddled around the round bulb-screen television set to watch ordinary people [who] looked like us, guess music trivia to win money, writes Kneo.

There is an interesting provocation introduced by Kneo’s placing of the words Jam Alley and ritual alongside each other in thought and articulation, especially when taking into account the socio-political tapestry and temporal moment the entertainment variety show was being produced and watched within at the height of its popularity- this being from the early 90s around 1994, to the early 2000s, let’s say round 2001.

Politically, 1994 was defined by the African National Congress winning the first so-called-democratic elections held in the country, Nelson Mandela becoming president and the continuing ruling presence of the Government of National Unity (GNU), which the apartheid National Party was also a part of.

The GNU was proposed by the ANC, as one amongst many measures conceived as a means of “ensuring inclusivity” during the transitional period from apartheid to democracy, it also established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Both the TRC and the GNU are contested and complicated parts of the history of South Africa’s transitional period and occurred at a temporal moment in tandem with the CODESA talks aka the talks that solidified the pitfalls of a complete Black liberation; political, economic, social and ontological.

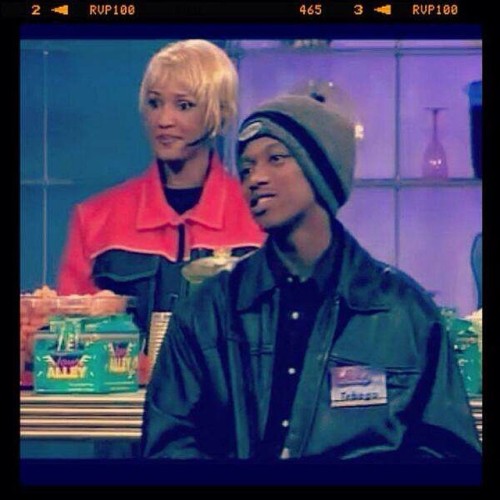

At the time, there was nothing remarkable about Jam Alley, nothing to write home about. Looking back now, that was the brilliance. It was a show with Black people, hosted by Black people, playing, laughing, taking chances, being silly. I watched it and it watched me back, wrapped me in simple joy and laughter as I screamed “middle centre!”.It was radical.

A ritual of witnessing in communal and collective joy, ushered in during evening light with the title sequences’ “Jam Alley ooooh yeahhh”, its beloved presenters and its radical Black aesthetic and cultural production, which touched us on our inside parts and called us by our names; amidst hope, chaos, violence, trauma, lies and promises.

It was in that context, that V-Mash called us “bangane” and guided us through rituals of joy. Here, there was no sacred sacrifice and holy punishment afforded Black people, we were human.

It could not have occurred to me at the time, but people that looked like us were navigating a promise of a better world while living in a nightmare. On the third of January, 1998, six policemen from the North East Rand Dog Unit set their dogs on three suspected illegal immigrants, allowing the animals to savage the three men while the officers hurled racial insults.

On the 10th of October, 1997, a combined version of Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika and Die Stem van Suid-Afrika became the National Anthem. The promise of a country where Black people could practice unbridled joy was being eroded and compromised; cynicism was beginning to settle as many became jaded with the world being offered to us as new.

The body remembers and mine still tightens at this memory of Black flesh being ripped and torn apart. The brutal footage was only released some 2 years after the actual incident via news reports, by then I lived with my parents in the leafy suburbs of Observatory on Frederick street, and a house with 2 German Shepards I would need to pass by on my daily walk to the Catholic school I attended, became a manifestation of a waking life nightmare.

There is a scene in the tv adaptation of the book Little Fires Everywhere, where the mother is talking to her child about the impossibility of being seen from a point of whiteness, how all it knows how to do is to see what you can do for it.

I think of this country’s relationship with V Mash and what she represented in the varying stages of her career in the same vain. In our collective adoration of and affinity towards Vinolia Mashego, her platinum blonde hair, care-free-Black-girl-manjiek-fashion-forward aesthetic, way ahead of its time and how she existed so completely for and in herself; a spirit of dangerous and impolite femme boldness permeating from the screen.

V Mash’s radical Black aesthetic production, was not one of respectability or palatability, and perhaps that coupled with the fungibility of blackness is also what transformed her into a literal site and symbolic sight upon which we could hurl our self-righteous and patronising new Black middle class and suburban frustrations at.

When we needed her to be that post-apartheid sweetheart that represented an aesthetic of Black life rooted in the social and cultural ecology of being from ekasi, that is what we made her, when we needed someone to become an example for how a particular kind of Black femme expression can be deemed “rude” or “hostile” and thus punishable by condemned exclusion – that is what she became and most recently, when we needed a moment of escape and some sense of national “closeness” while in isolation, in death she was resurrected once again as the country’s original “It girl” who paved the way for the many who came after her.

The outpour of love and condolences for her after her death, was both heart warming and simultaneously triggering given how she was forgotten both by her industry and us as a nation when she was at her most financially and emotionally vulnerable.

This is by no means a romanticisation of Vinolia Mashego, nor is it an attempt to deify her through perfection in death, for only those who truly knew her personally can account for her character but it is a critique of our so called love for those Black femme cultural icons we seem to only care about in death. Vinolia V Mash deserved so much more than us.

She recognised [our] humanity and broadcast it into our living rooms for all of our families to practice in. V-Mash loved Black people and gave us permission to unconditionally love ourselves too without having to earn university degrees, without having to get married, have children, buy houses in the suburbs, but love here, in the places and spaces we were, in this moment, with these bones. V-Mash went on into other spaces in the lives of Black people and did the same. That is her legacy, her unconditional love for the unbridled joy of Black people, and that is how I will remember her.