Black Brazilian singers and artists are “finally” talking about love and affection in their music and work — in addition to stereotypes, masculinity, patriarchy, racism and censorship.

With the continuous breaking down of barriers, combined with recent access to power and the market, and above all, narratives of protagonists and valorisation, more people can be proud of their collective trajectories and achievements.

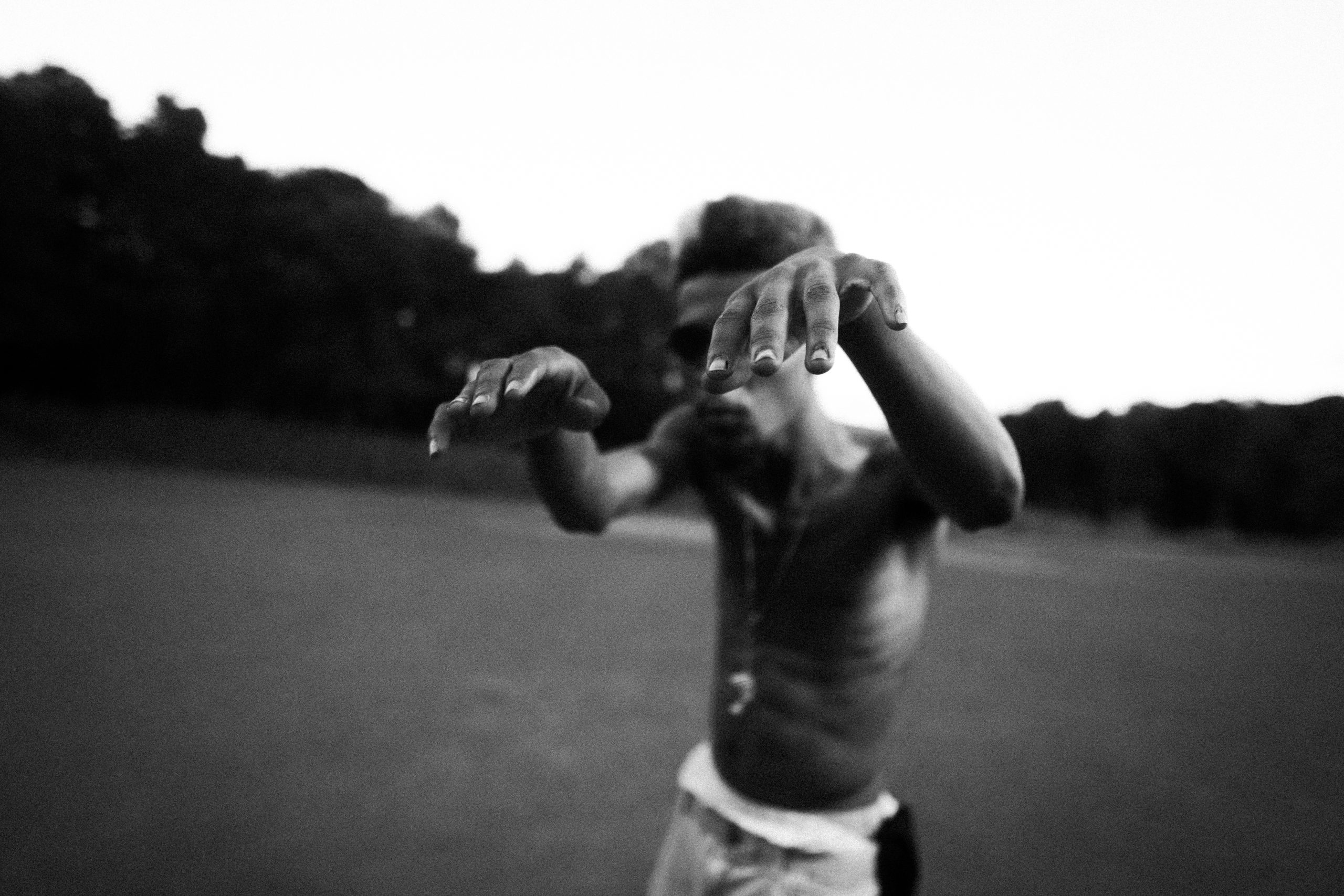

We inaugurate a moment in which artists can navigate through a diversity of themes, with autonomy and tranquillity. Today they sing, dance and paint with love and affection, along with exploring themes of racism, violence and death, all matters of urgency.

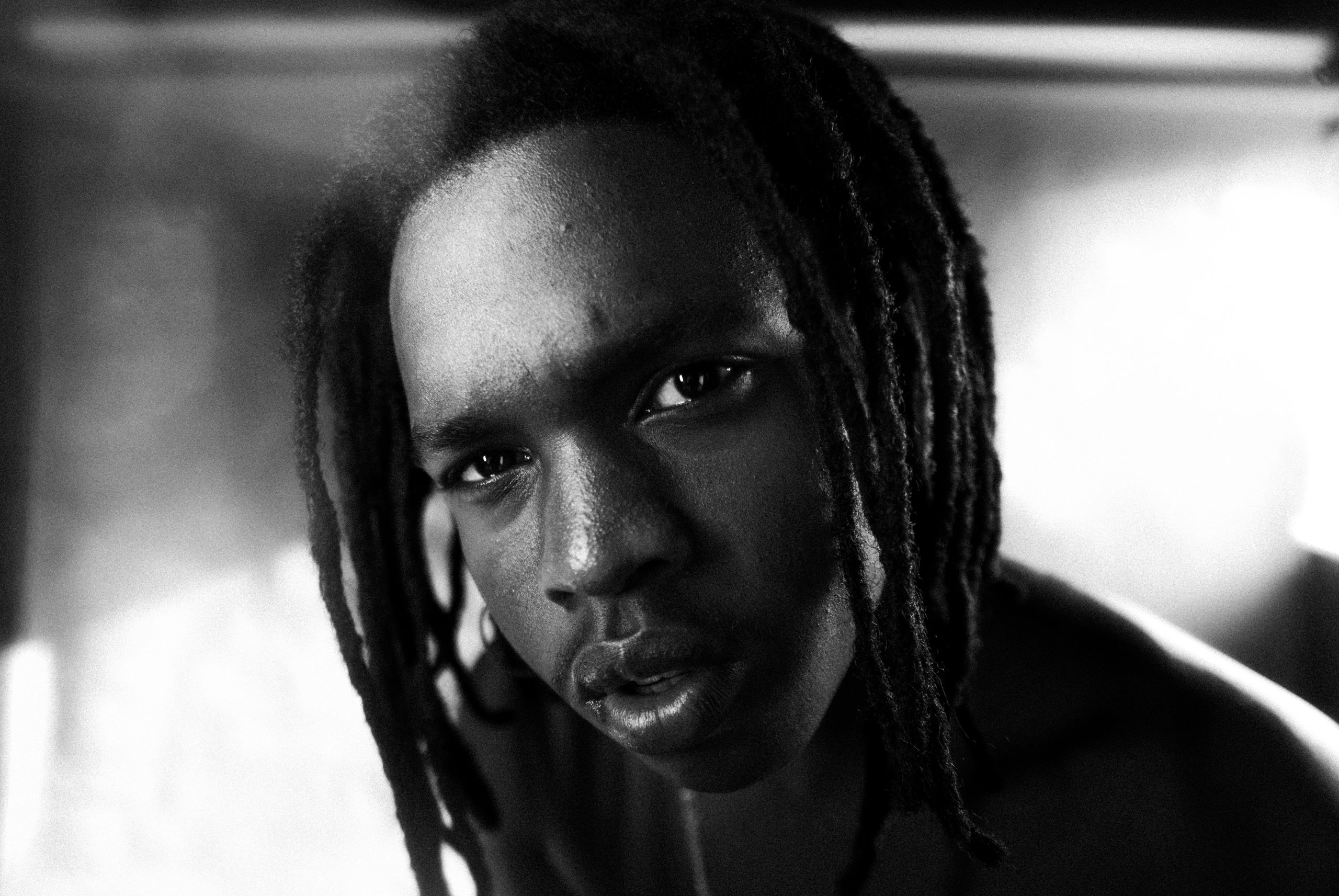

Singers like Baco Exu do Blues and Larissa Luz — as well as Bivolt, N.I.N.A, Ludmilla, Tasha & Tracie, Emicida, Criolo, Marabu, Kae Guajajara — embrace boundless love.

Alongside artists such as Bernardo Conceição, Caio Rosa, Larissa Souza, Heloisa Hariadne, Yedda Affini, Fernanda Souza, Silvana Mendes, Helen Salomão and Wendy Andrade, who dedicate themselves to rebuilding narratives and possibilities for Black communities and their relationships with affection and love.

These artists use vulnerability to free themselves from limiting and racist stereotypes and associations such as “angry” and “violent” — intimately linked to the way in which the responses of these bodies are read by colonial structures and logic.

bell hooks teaches us in the text On the uses of anger that, “women responding to racism means women responding to anger; anger at the exclusion of unquestioned privilege, racial distortions, silence, abuse, stereotyping, defensiveness, misnames, betrayal and co-optation.”

The feminist intellectual and scholar also states that “as long as Black anger continues to be represented only as malignant and destructive, we will not have the vision of militancy necessary for transformative revolutionary action”. Therefore, hooks suggests, and places anger, as a tool for positivity, confrontation and emancipation.

This expansion and conquest of freedom and autonomy is only possible if we evaluate the trajectory of rap and funk in Brazil and its impact today. The starting point for this movement begins with Racionais MCs, on the album Raio X Brasil, from 1993, followed by the classic Sobrevivendo no Inferno, from 1997 — considered by many to be the most important album in Brazilian rap.

These records inaugurated, for a large audience, hip hop as a music of denunciation and criticism — in this case, especially aimed at the periphery of São Paulo. His tracks are still Brazilian rap anthems and, because they are so powerful, they have become an essential part of most Brazilian youth’s first contact with political formations.

Racionais MCs were the target of a lot of criticism, censorship and violence, and this still occurs, especially in manifestations such as spaces of funk and dance — spaces established with the intention of coexistence and multiplicity in a contemporary context.

These are movements that coined a concept of pride and recognition, as the researcher Tiarajú Pablo D’Andrea states in The formation of peripheral subjects: culture and politics in the periphery of São Paulo, his doctoral thesis at the University of São Paulo. The sociologist explains that “periphery has come to designate not only poverty and violence, but also culture and power.”

And if Brazilian hip hop is taking off in several directions today, it is necessary to recognise the weight of recent names in the scene, such as Jup do Bairro, Enme Paixão and Sodomita. Women who identify as part of the acronym, while rejecting the label of an LGBTQIA+ song. The songs and their lyrics are social thermometers, and the current expansion of themes and perspectives is a reflection of a response to the demand and struggle for space and freedom.

Whorehouse, for example, was dominated by men talking about women’s bodies and today, through a sense of humour and good doses of real-life feminism, femmes occupy the space and complex mission of building a narrative of their own for objectified bodies and socially abused.

At first, “sexual themes seemed the only possible way for these women to be heard within a patriarchal market structure, blurring the line between patriarchal objectification and the freedom of sexual self-expression,” as music researcher GG Albuquerque, founder of the portal O Volume Morto, in the article Carol and the borogodó: sexuality as a vital force, writes.

He goes on to say that today these bodies are not silent and communicate their desires and subjectivities “bringing to themselves the pulsating desire as a detonator of norms and structures of submission, finding in themselves, in their own bodies, the renewing source of chaos.”

In art, it is worth mentioning movements of rupture and transformation carried out by independent Black artists, creatives and curators, without great support and who are moving the structures of Brazilian art from their projects and connections such as Carollina and Jaime Lauriano, Amanda Carneiro, Hélio Menezes, Diane Lima, Nathalia Grilo, Ode.

As well as HOA Art, by gallerist and multi-artist Igi Ayedun, the first Black woman to found a gallery in Brazil and is now also in London and on the global circuit representing young, Black and Latin American artists. As Igi says, “reality is a gap in dreams”, and through the circulation and appreciation of these narratives, she builds fragments and projects of freedom.

Beatriz Nascimento, a Brazilian historian and writer, describes quilombos as “African institutions in Brazil” and “alternative systems of organising Black people and other dissident bodies”. Thus, Black culture is not just a matter of influence, it is the origin and basis of the most reproduced and consumed musical genres, expressions, rhythms and aesthetics in the world.

They work like the new contemporary quilombos of today, by creating new systems of belonging and dialogue for these bodies.

In addition to establishing affection as a centre and radical project against the constant presence of death, they also engage technologies, constructions and languages that expand to generate comfort, freedom, and celebration. To understand who creates narratives in the present, is to understand what is planted for the future.