The exhibition “A House is not a Home…” at the KZNSA Gallery which closes on 14 July, delves into the multifaceted concept of home through the works of over 30 exhibiting artists. This Q&A feature engages with six of the artists—Sphephelo Mnguni, Londiwe Mtshali, Siviwe Jali, Jess Bothma, Rachel Baasch and Lusanda Ndita—to explore their interpretations of home as expressed through their art, their processes to creating and choice of medium and materials.

Each artist provides unique insights into how their personal experiences, cultural contexts, and creative practices shape their work. From Sphe Mnguni’s use of oil on canvas to Londiwe Mtshali’s printmaking, Siviwe Jali’s furniture designs, Jess Bothma’s vibrant drawings and trojan horse sculptures, to Rachel Baasch’s monoprints layered in political activism and Lusanda Ndita’s screenprints contemplating intimate family journeys, this dialogue reveals the diverse ways in which the notion of home can be represented and reimagined in contemporary art.

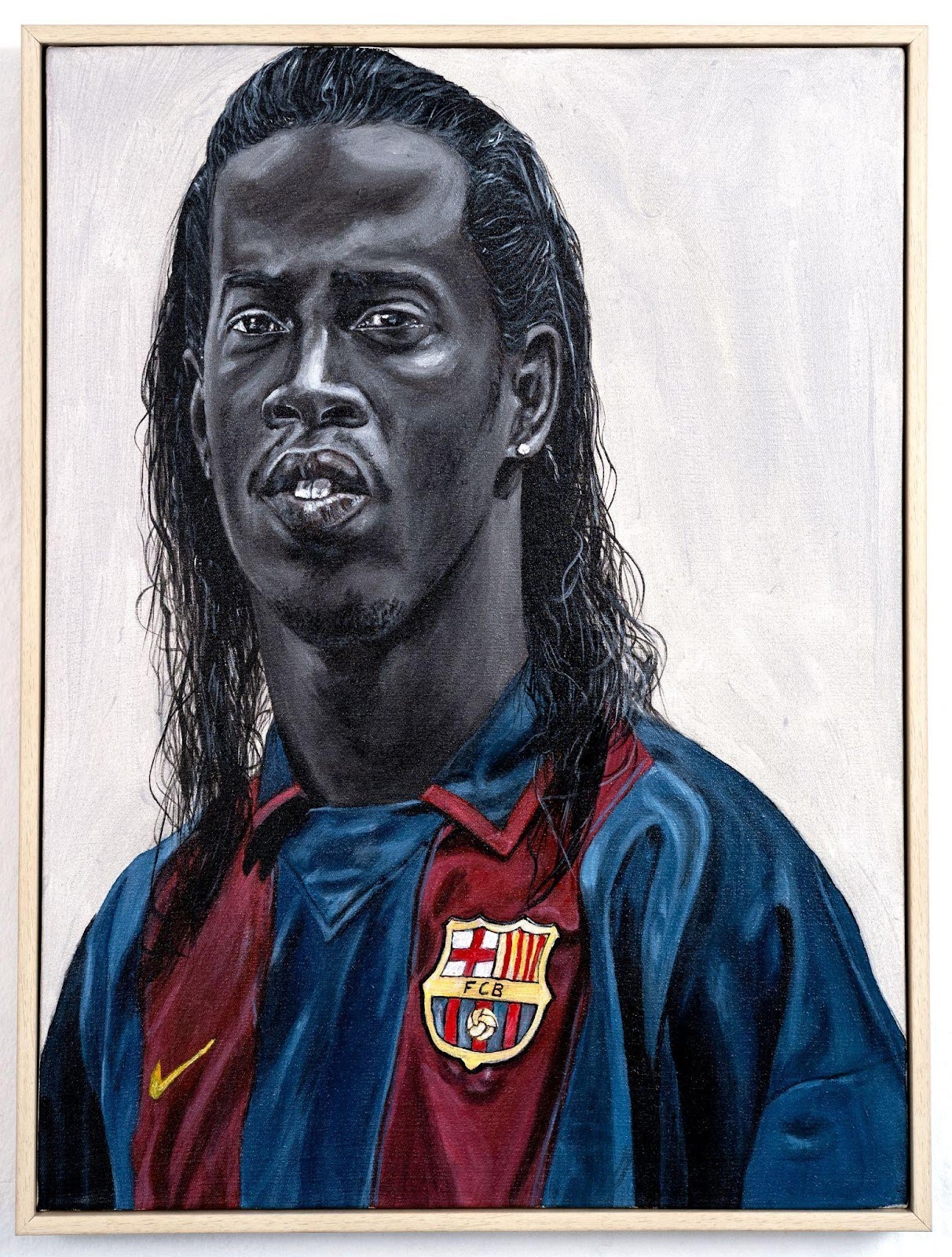

Sphephelo Mnguni (SP)

How does your work in ‘A House is not a Home…’ relate to notions of home?

SP: Reflecting on the title of the show evokes feelings of nostalgia for a time when my family was united in the face of challenges. Coming of age in a bustling household characterised by parental dedication to ensuring a high quality of life through industrious efforts, my siblings and I were expected to excel academically in alignment with this familial ethos. Our evenings were meticulously scheduled with various tasks aimed at readiness for the subsequent day, followed by an early bedtime to ensure adequate rest for the demands of the following day. This demanding routine left little room for familial bonding and recreational activities.

Nevertheless, instances of profound joy and unity emerged, fostering close bonds among us during weekends and holidays. These occasions provided respite from the demands of school and work, allowing us to relax and savour the present moment. Our shared passion for soccer served as a unifying force like no other. Recollections of gathering around the small screen at my grandmother’s house to cheer on our beloved team fill me with fond memories. In those instances, we set aside our concerns and adversities to revel in the simple delight of the sport, embodying a sense of unity and solidarity.

Sphephelo Mnguni, A Beautiful Reflection, 2024, acrylic on canvas

Sphephelo Mnguni, A Beautiful Reflection, 2024, acrylic on canvas

Looking back on those soccer matches engenders a sense of happiness from my childhood, delineating the strong familial bond that persevered through trying circumstances. Despite the scarcity of time and resources, our family was enriched by love and cohesiveness. These reminiscences will forever hold a cherished place in my heart, evoking a smile whenever they come to mind.

In the show, you use oil on canvas, is there a reason you work with this medium?

SP: Acrylic painting possesses a distinctive quality characterised by vibrant colours and expedited drying times – incomparable to oil – enabling the artist to incorporate multiple layers into the composition. I actively engage in the utilisation of numerous layers within my artistic practice, not only to enhance the depth of the artwork but also to symbolise the complexities of life. Similar to the process of painting, life may present challenges and setbacks, however, through perseverance and continued effort, additional layers can be added, resulting in a refined and exquisite final piece that mirrors the evolution and maturation experienced throughout the journey.

As a Durban-based artist who has shows across the country and internationally, how can local artists connect outside of this home?

Art holds a profound value for me due to its role in enabling immediate connections among individuals regardless of their physical proximity. Witnessing individuals engage in discussions about their interpretations and emotional responses to a particular artwork is a uniquely enriching experience, particularly when observing the debates and connections that arise within online spaces through comments. The current online landscape serves as a connection hub for artistic engagement, allowing art enthusiasts to interact with artists and present their perspectives to a broader audience beyond physical exhibitions. Notably, many art shows and artist collaborations stem from online interactions, highlighting the accessibility and reach of online platforms in fostering artistic dialogue and appreciation without the limitations of physical presence.

Londiwe Mtshali (LM)

How does your work relate to notions of home?

LM: I’m currently working through the idea of home as a site of memory, a site of healing and most especially homeownership by black women in my master’s research so these works were created as a consequence of that research. Paths to Home is a work that was made as a meditation on the journeys that different generations of women in my family have taken in order to own a home. To ruminate about the ways those very hardships are often covered by the furnishings of the home itself. Lace Front is about the memories of home and the fragility of family life. In particular, as a celebration of kinds of objects and furnishing in the homes I grew up in.

In the show, you printed on screen prints with particular colours, is there a reason you work with this medium and colour palette?

LM: I like printmaking, it’s a medium that I have used since undergrad so I feel like there is something about it that I have come to understand quite well. Most importantly there is something about printmaking that lends itself quite nicely to the overall language around homes, buildings and mapping especially if you think of cyanotypes as blueprints. The colour palette used in these works is similar to my overall practice and is very close to my earlier works that explored links to spirituality in my family, specifically garments like amabhayi and clerical regalia, these colours became symbolic and for me felt like another layer to add to my practice. If you look at any work I’ve produced in the past four years you’ll see a lot of warm hues and pale yellows and as I make more work I have been getting into earthy colours that mimic landscapes.

Londiwe Mtshali, Lace Front, 2024, Silkscreen

Londiwe Mtshali, Lace Front, 2024, Silkscreen

What is your approach and process to artmaking?

LM: My approach usually depends on what the work I’m making is for and whether the work is informed by a particular idea or is a result of experimentation. I usually start with storyboarding if I’m making video work; sketching or collaging for print works. If I’m making a textile work I will explore my favourite fabric shops’ inventory to get a clear understanding of texture and colour. After all of that, I workshop ideas and edit until the final project emerges.

Siviwe Jali (SJ):

How do your furniture pieces in the show try to elevate design?

SJ: My pieces elevate design in several ways. Firstly, by using materials such as mild steel, which is the most common and cheapest form of steel. By using inexpensive materials, I aim to show that it’s the design, not the materials, that adds value. Good design can elevate even the simplest materials.

What is the inspiration behind the design pieces?

SJ: My inspiration is multilayered, drawn from my interests and experiences. Aesthetically, I’m inspired by brutalist architecture. On another level, industrial processes influence how I design and construct objects. The way things are made is a significant inspiration. Additionally, I’m driven by an emotional direction, reflecting on how it feels to be alive in the present time and conveying that feeling through my designs. Design should evoke emotions as well as be functional and aesthetically pleasing.

Installation view featuring Siviwe Jali’s chair, carpet and server Mild Steel designs. Photograph by Paulo Menezes

Installation view featuring Siviwe Jali’s chair, carpet and server Mild Steel designs. Photograph by Paulo Menezes

In the show, your designs have particular colours (red, black, and white). Is there a reason you work with this colour palette?

SJ: I was inspired by my Zulu background and izimbadada – a sandal made from up-cycled tyres, which traditionally uses red, black, and white. Despite using modern design, I wanted to reflect my Zulu heritage in the aesthetic. This combination aligns with my preference for modernist and minimalist design. Showcasing that design and African aesthetic references blend seamlessly into each other.

Does mass production democratise or dilute design? How do you navigate this as a designer?

SJ: Mass production can do both, depending on the strength of the design. For instance, no one complains about the dilution of design with iPhones, even though millions own them. I believe in democratising objects through mass production and don’t see it as diluting design unless the design wasn’t fully considered for that scale. Everyone is entitled to have access to beautiful objects, not just the top 10% of the population.

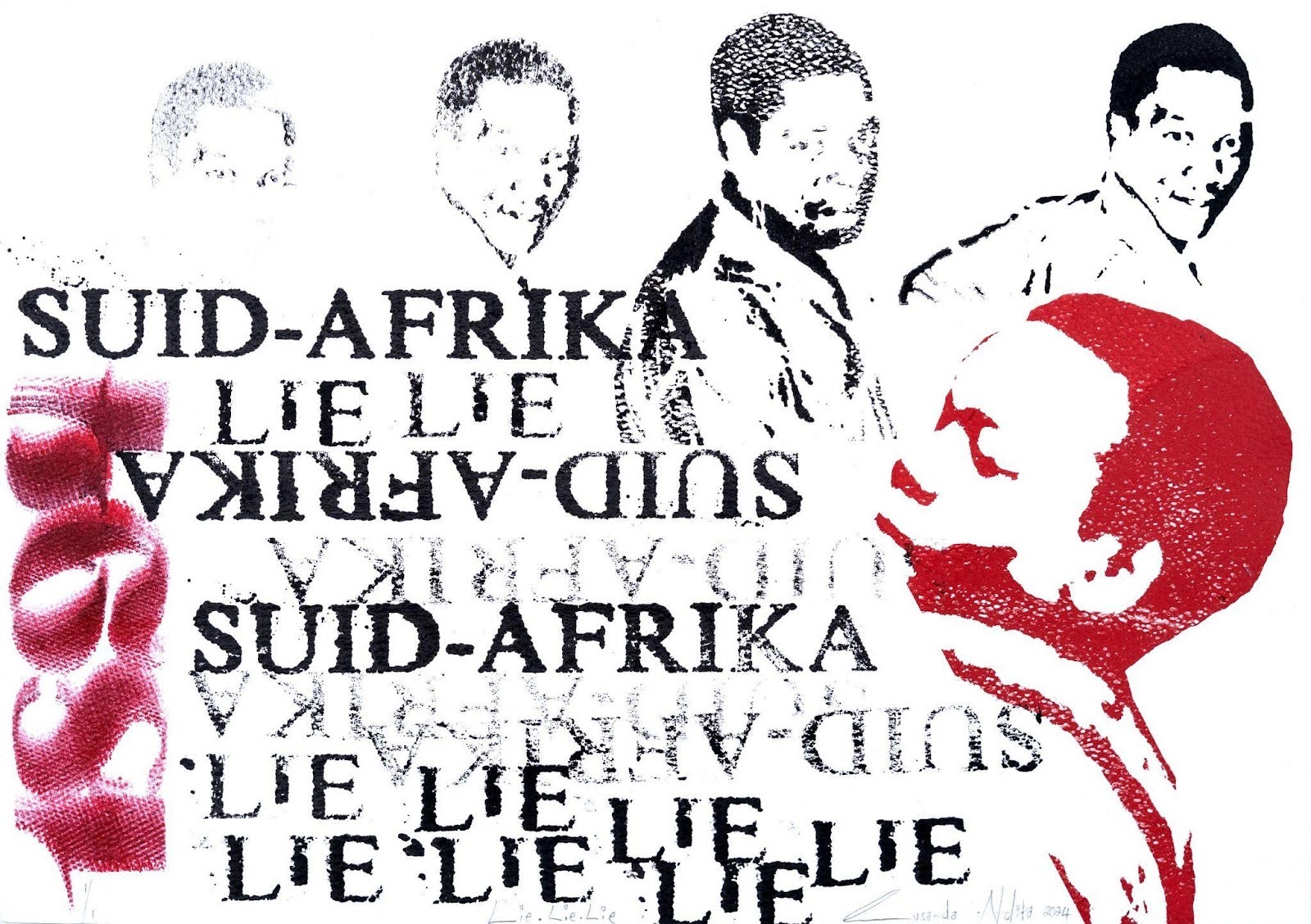

Lusanda Ndita (LN)

How does your work relate to notions of home as an artist?

LN: I investigate the notion of belonging in my work through the lens of my family’s stories, especially my grandfather’s, who lived in the Transkei homeland, which was the first Bantustan; he was considered a ‘Transkeian’ citizen. He was contracted as a migrant worker to work in the Cape (an area that didn’t consider him a citizen). I am interested in the disjuncture of belonging, where home is neither physical nor bodily, but where the psychological and spiritual are at balance.

Lusanda Ndita, Lie, Lie, Lie, 2024, Silkscreen print

In the show, you printed on screen prints with particular colours, is there a reason you work with this medium and colour palette?

LN: Red is a metaphor for the Xhosa process of ‘becoming’ and transitioning from a state of boyhood to manhood. As a rite of passage, a boy goes to entabeni and has imbola (red soil) applied on his body for a period of time before ascending to manhood. I work with screen print because of the role it played during the apartheid resistance movement in the making of posters and t-shirts.

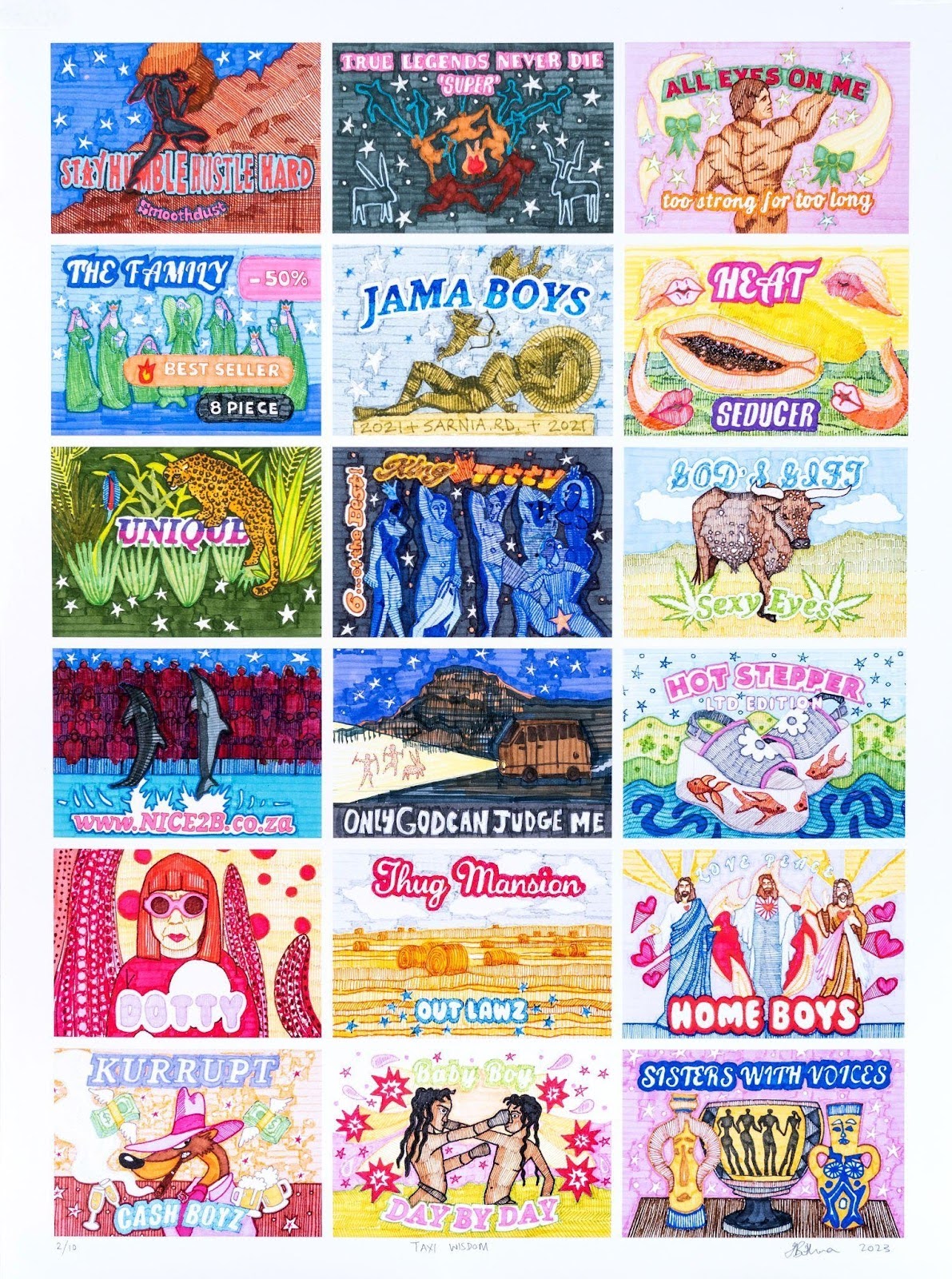

Jess Bothma (JB)

How does your work relate to notions of home as an artist?

JB:I think my work is always unpacking ideas of home; I am influenced by the spaces that I occupy and what I see around me. I think this is probably the case for most artists, we are processing our surroundings all the time and making sense of things. Much of my work is also exploring belonging and un-belonging within the context of South Africa. We have an incredibly problematic past and a precarious future. The idea of home or having a home and sense of location seems to me, to be a fluid thing. Some people belong more than others in different times and contexts. Much of my work looks at how we assert our identities and sense of belonging, un-belonging, security and insecurity. I think this can be seen in both ‘taxi wisdom’ and ’empathy’.

In the show, you have sculptures and smaller prints that use koki pens, is there a reason you work with these mediums and colour palette?

JB: I am mostly a 3-Dimensional maker, but I do love the immediate joy of working in 2-Dimension. My drawings and koki pen works really started as a form of planning and from making colourful personalised birthday cards. I started the ‘taxi wisdom’ series as a fun way to kind of hold onto some of the things I had seen on taxis on a daily basis.

South Africa has its own dynamic and fluid energy and identity, and there is a seemingly site-specific phenomenon of texts on taxis that I have been recording while travelling into and out of Durban along the M4. The texts really appeal to me, sometimes the font and, the abstraction or the prophetic nature plastered across a moving vehicle. I have tried to contextualise them into drawings, imagining what these words meant to me, sometimes in the context that I see them, the place or road as well as my own associations. It feels like an authentic perspective and way to engage as an observer, through drawings with joy and lightness which in contrast is quite oppositional to the turbulent nature of the taxi industry. The drawings have become a way for me to engage with my city, to feel connected and part of this busy, dislocated, chaotic and completely charming place, my home.

Jess Bothma, Taxi Wisdom, 2024

’empathy’ was made to try to explore what the fabric of a South African heart is made from. I’m quite sure most South Africans are empathetic and thus traumatised. We come from a people who could feel the earth, trees and animals in their own bodies, yet here we are, anxious, and so much is changing all the time. Our hearts are on fire, because whether we harm or help or watch we are heart broken. We have so much, this great capacity to love and share and be profound, but we have fences to survive and dogs to protect and guns and bullets to defend and destroy. Our South African hearts are full of bold colour and joy but always a broken heartbeat away from danger.

Colour for me is also a central tool for my practice across mediums. I feel it captures moods, it highlights and it has a kind of association and poetry of its own.

As an arts educator, what type of environment do you think is good for art students?

JB: A safe one. Despite that seeming like a simple answer it is a very difficult thing to achieve. In the traditional sense, students should have access to a safe environment to work and learn in. I think their creativity needs to be held in a safe environment, this environment should not be too indulgent or sensitive, mindful perhaps but also have some rigour to help students figure out for themselves what they are trying to do. I think artworks can always get better, but your sensibility is marked by the point at which you stop. Unfortunately, I think we are beginning to foster a sense of mediocrity, for a number of reasons, that come from not being able to have difficult conversations. I try to create a safe space for students; I am always available and will tolerate any questions, I try to help them but I also try to say the difficult things, like when they haven’t pushed enough or when they get distracted. It is a fine balance to try to create a shared sense of vision with someone where there is a power dynamic, trust is essential.

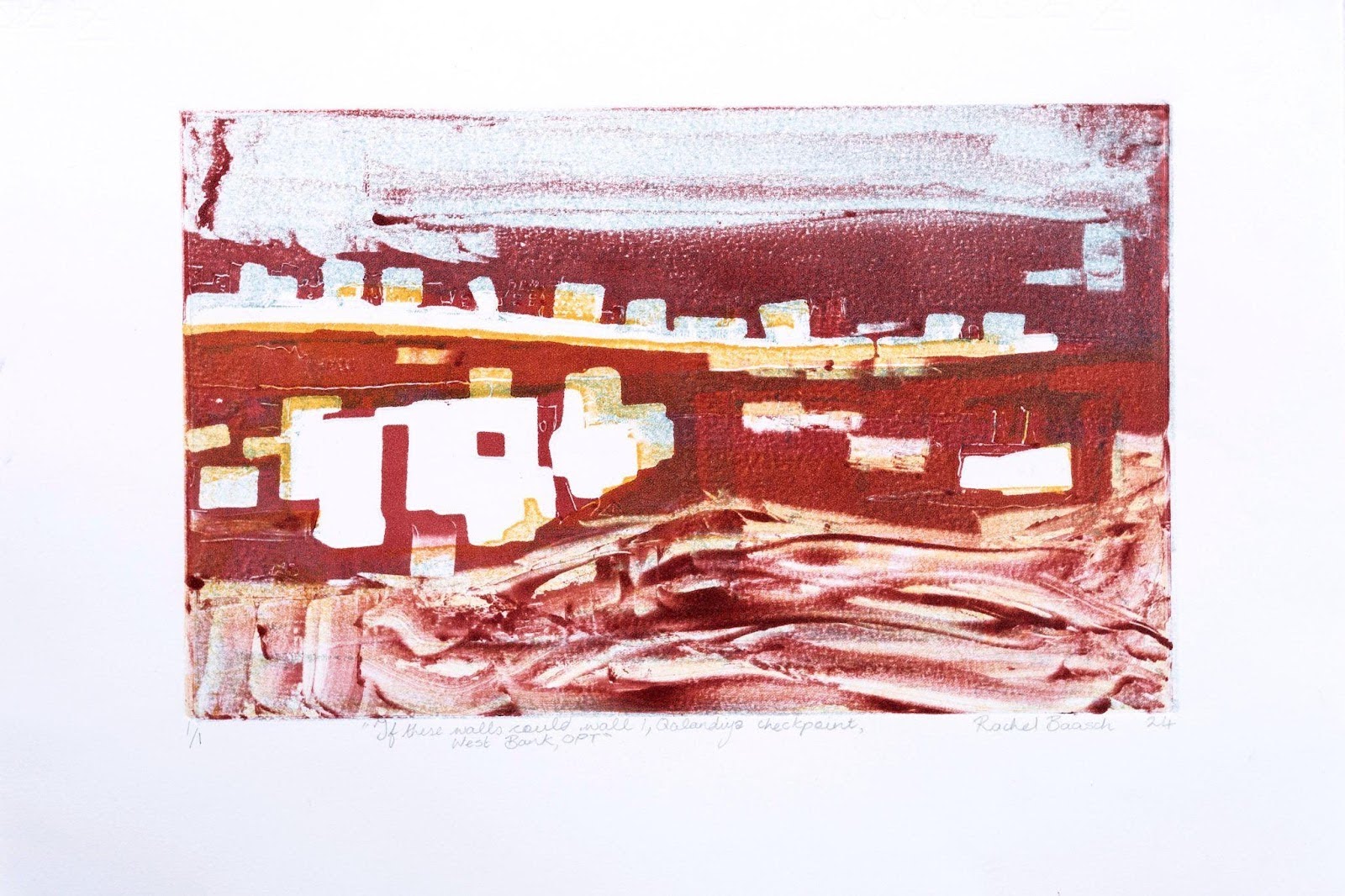

Rachel Baasch (RB)

How does your work relate to notions of home as an artist?

RB: My work is focused on physical, ideological and psychological barriers, borders and structures of division. This series of works look at the growing phenomenon of ‘hard borders’ in relation to the Israeli apartheid wall in the Occupied Palestinian West Bank Territory and ‘Fortress Europe’ in the cities of Ceuta and Melilla. These hard borders articulate an ‘inside’ and an ‘outside’ that define the lines of exclusion and inclusion in these locations. This geo-political phenomenon results in forced displacement, violent immigration policies and the dispossession of land. This has both a direct and indirect impact on the individual experience of home and the way in which the individual conceptualises themselves in relation to the nation-state as a home. My work also explores the notion of home in terms of securitization and the fear-based politics that result in the construction and maintenance of these ‘hard borders’.

Rachel Baasch, If these walls could fall I, Qalandiya Checkpoint, West Bank OPT, 2024, Monoprint on Fabriano

In the show, you have monoprints, is there a reason you work with this medium?

RB: While working on my art history research, I started to document these hard borders and sites of division through photography. I recently began exploring the medium of printmaking because I am interested in developing a visual language that engages with the way in which one sees or fails to see violent mechanisms of division and socio-political exclusion. I found that the method of monoprinting that I have learnt under the mentorship of John Roome has an ephemerality and haunting quality that allows you to imagine that these seemingly fixed, immovable borders could be removed, wiped away. The monoprint technique that I use allows me to play with presence and absence through a process of reduction and layering.

The exhibition is curated by the KZNSA exhibition sub-committee, as an effort to fundraise for the gallery. Consider donating here and/or purchasing an artwork from our online catalogue.