Goodman Gallery prides itself on its unmatched stable of international artists. Recently, the leading gallery boasted Light Blue Violet, a solo exhibition by ruby onyinyechi amanze, an artist who divides her time between Philadelphia and Brooklyn, USA, considering multiple locations as home. The Johannesburg show was typically well attended. As visitors stepped into the space in irregular intervals, I was afforded the opportunity to speak with some of the Goodman staff, including Christa Dee, former BubblegumClub editor, as well as the artist herself.

The increasingly popular ruby onyinyechi amanze (b. 1982, Port Harcourt, Nigeria) is an artist of African heritage and British upbringing. amanze earned her B.F.A. summa cum laude from Tyler School of Art at Temple University and her M.F.A. from Cranbrook Academy of Art. Her work is inspired by photography, textiles, architecture, and printmaking, focusing on how to preserve the weightlessness of paper in her large-scale, multi-dimensional drawings, emphasising spatial negotiations within dance, architecture, and design.

amanze was a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, from 2012 to 2013. Her 2022 exhibition DUETS in London was a pivotal moment, as it translated her drawings into a three-dimensional format. Recently, she completed two-year residencies at the Queens Museum and the Drawing Center’s Open Sessions Program in New York. amanze has exhibited her work internationally in cities like Lagos, London, Johannesburg, and Paris, as well as at the California African American Museum and the Studio Museum of Harlem.

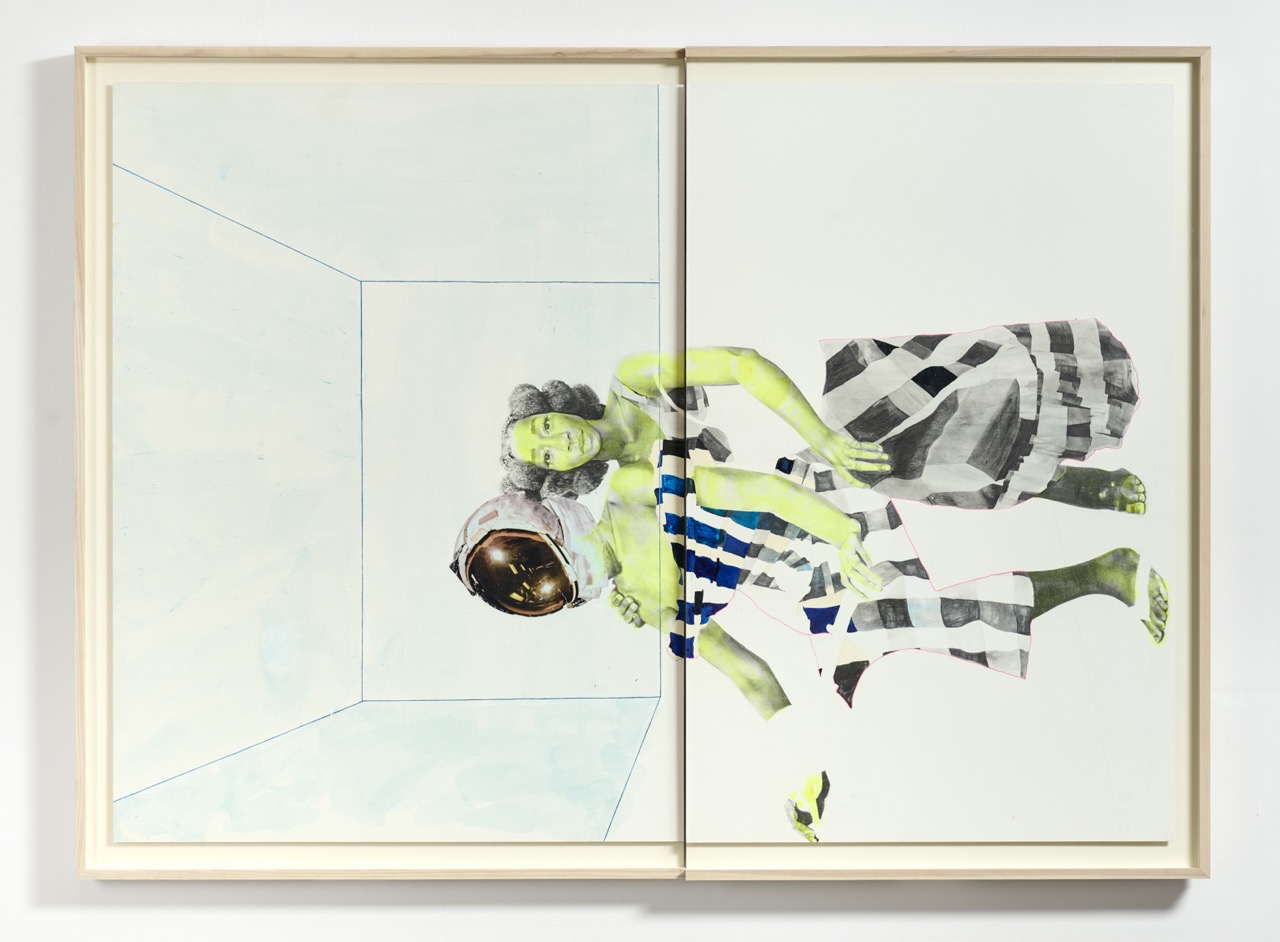

Goodman’s Dee generously walked me through the exhibit, explaining: “(The figures) are a cast of characters she(ruby)’s been developing over the past decade. Initially, they were quite personal, with their own stories and narratives, though I can’t share too many details. Over time, however, these characters have evolved—or rather, de-evolved. They’re no longer intimately connected to her or tied to a structured narrative. Instead, they function more like puzzle pieces or formal objects that she integrates into her work.

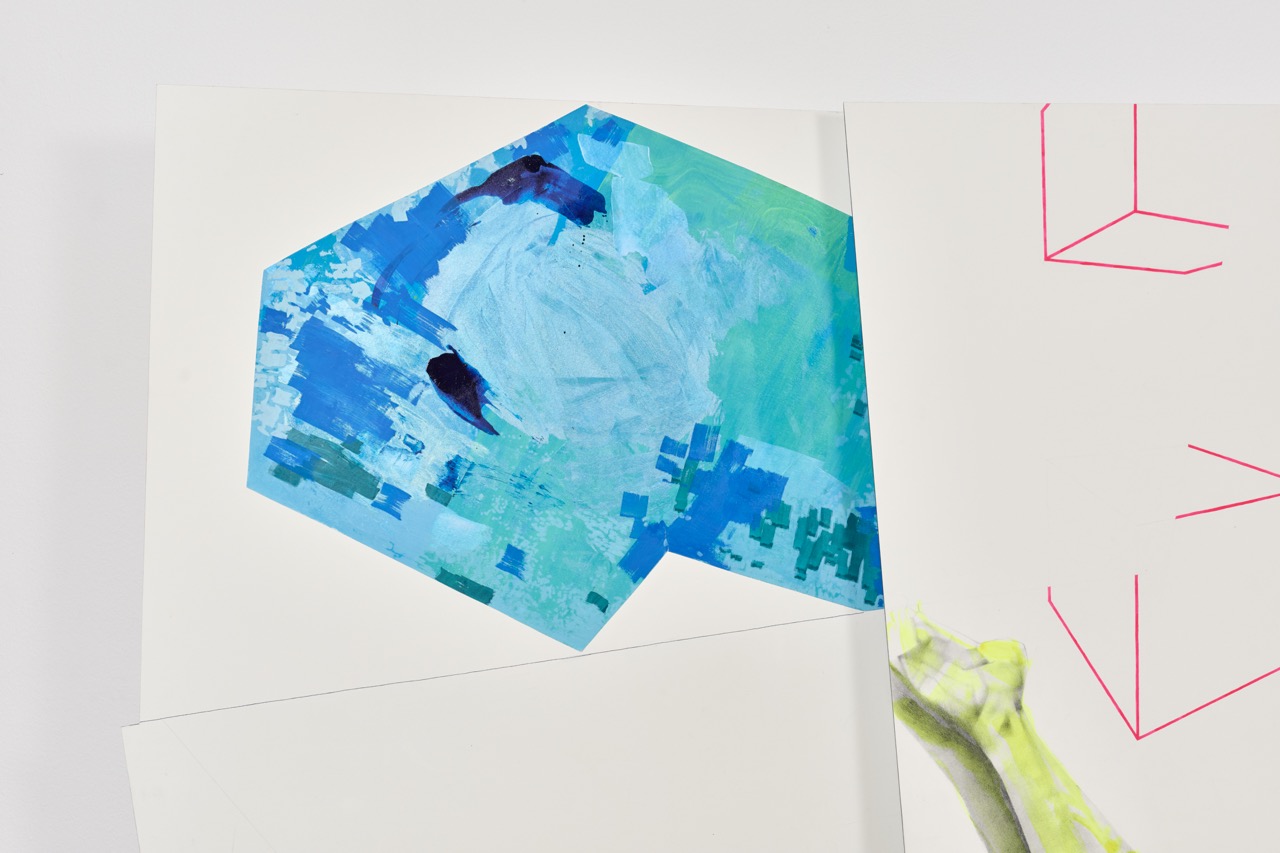

She’s also become increasingly interested in the idea of a swimming pool, which has recently emerged as a recurring object in her practice. This piece, for example, is site-specific, created according to the gallery’s dimensions. It consists of three panels, with a deliberately loose hanging meant to mimic the movement of water.”

In the space, amaze said, “ So, my work for several years now has been a continued body. I’ll have different chapters, which are the shows, but I’ve been thinking a lot about space and how space is important. Space is malleable and inventive and playful and also a thing that we construct with lines and shapes and doors and borders. So taking that and using architecture and dance as 3D spatial practices to inform what traditionally is a 2D practice. The work is about the infinite stretchiness of space and having that come out in the presentation as well.”

Walking into the space, the viewer is confronted with an overwhelming amount of white space, which is not necessarily an unusual tactic on the part of Goodman, but the artist says this is also a key part of her own practice. amanze’s current work, including the site-specific piece Infinite Deep Blue, contained [POOL], which Christa Dee mentioned, seems to have been crafted with the gallery’s white cube parameters in mind, but it’s pushed up against a corner near the entrance. Apart from this, there is a lot of white space left for the viewer to ponder.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler‘s 1883 exhibition at London’s Fine Art Society is often regarded as the first “white cube” show, with white artworks framed in white and set against a white backdrop. By 1976, Brian O’Doherty criticized the white cube aesthetic as a modernist fixation. So amanze’s work contributes to an ongoing, non-linear narrative and while it does create a self-imagined, chimeric universe it also pushes up against and exists within what we could call reality, employing visual elements that follow a shifting yet rather insistent lineage.

With these considerations in mind, this exhibition’s use of white transcends surface. The intentionality of this artistic choice moves colour from mere aesthetics to a vehicle for strategic artistic propositions and declarations, embodying absence/presence in the space. It seems amanze really wants us to notice. She invites viewers to engage in “deep seeing,” inspired by composer Pauline Oliveros’ concept of “deep listening”, which encourages active, conscious observation rather than passive viewing. So, amanze is insisting we see what’s made plain.

amanze conceptualises her drawings as physically enterable rooms. As well as the artworks on show, most of which are large scale, the gallery space is imposing—reminiscent of most rooms we inhabit—flooded with whiteness. When there was colour, it was blue or green, mostly cold colours, mimicking the theme of the pool—save the comforting characters with varying skin surfaces and tones. While the surfaces were never soft or warm, her figures were. Strikingly recognisable and quite pleasing in their pristine familiarity.

While each shift in composition may seem minor, collectively they create a disorienting and reorienting experience for the viewer, influencing how the artworks relate to the exhibition space. amanze’s characters and the various forms, engaging materials such as graphite, ink, and photo transfers, almost seem to be in some abstract battle with the emptiness that surrounds them. What’s at stake is the age-old tension between form and function, with the show adding tricky nuance to what it means to be a Black femme painter in an ostensibly white world.

When I asked if she had any words for our readers, amanze said, “I’d say the first word that comes to mind is integrity. It’s easy to get caught up in the external side of art—business, recognition, all of that. But being an artist comes from a place of curiosity. And art should be fun—I think we have to remember that. It’s okay to want your work to be seen. But we need to keep the gift close, protect its integrity, and enjoy the process—experiment, play, make mistakes, ask questions. If we do that, hopefully, we can steer the ship, cos we’re in charge.”