We live in a society of images, mediated through black screens. To be alive in 2018 is to be subjected to a barrage of visuals on computers, smart phones and tablets- news, adverts, memes and the selfies and Instagram imagery that is curated with all the care and detail of Renaissance painting. Meanwhile, technological advancements expand the scope of how images can be manipulated and how the presentation of reality can be intimately shaped. This strange new visual landscape has become naturalised as the backdrop of everyday life, but if we take a step back, we can see it not so much as an organic outcome of technological acceleration but as an expression of the political and ideological forces which dominate society.

The history of capitalism is a relentless hunt for new territories to exploit. The last 500 years of imperialism and colonialism is a story of natural resources being hacked, slacked and dragged from the earth, and of the human labour necessary to mine this wealth. But the vectors of exploitation expand as technology accelerates. A current business buzz phrase “data is the new oil” reveals how the extraction of personal information from smartphones and the internet has become the new frontier of accumulation [1]. With developments in data mining and algorithmic manipulation, every individual user becomes a lucrative source of uncut information which is refined for marketing and political manipulation. Unconsciously, users labour in “online persona factories” [2], producing an endless stream of personal information.

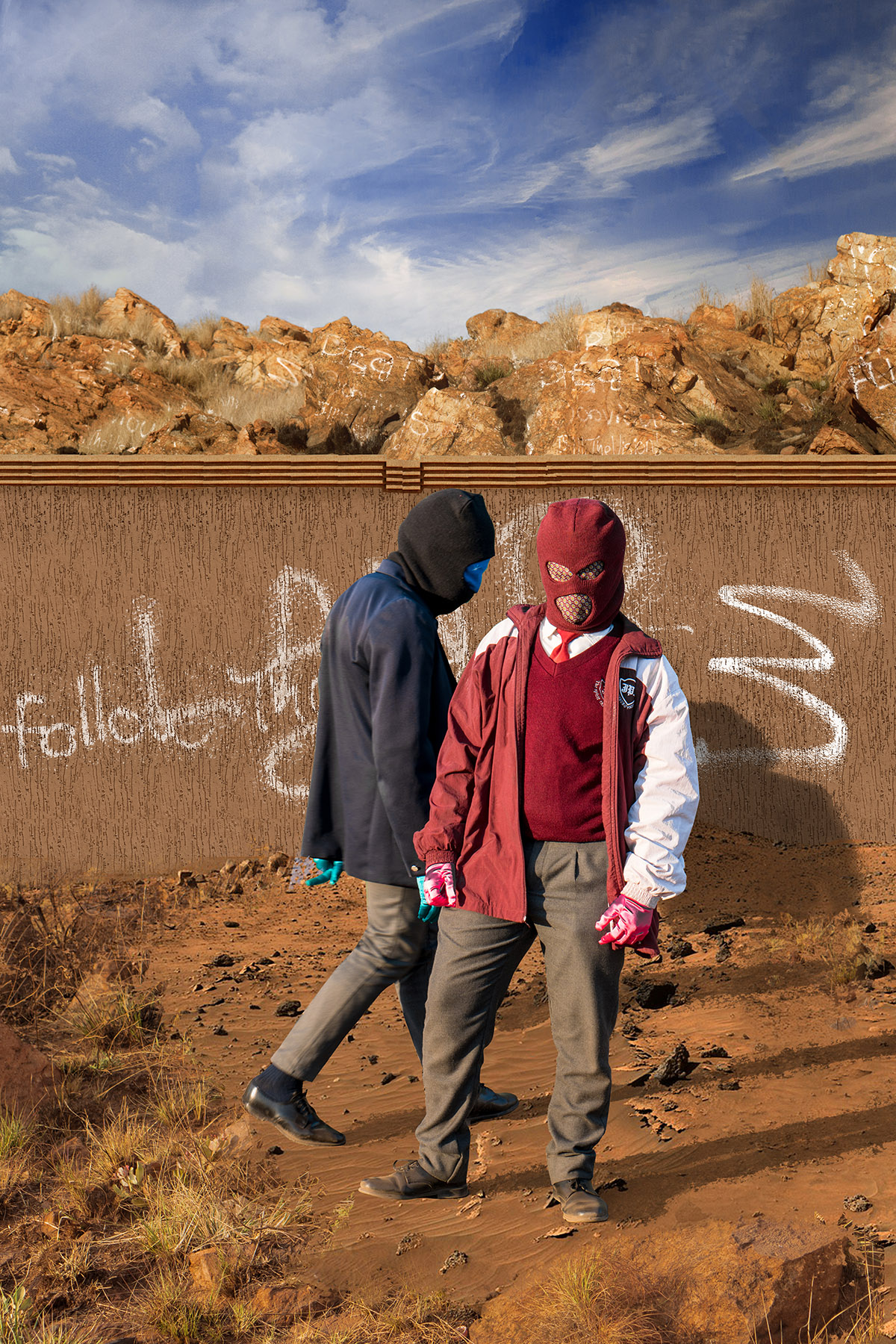

The proliferation of data mining has a dark resonance with South African history. The discovery of diamonds and gold in the late 19th century lead to a forced process of industrial modernisation, which left a nightmarish human toil. Mining capital’s endless hunger for the labour and control of black people was the pivot around which Apartheid rotated, and which shaped the fractured city of Johannesburg. The entire state apparatus was a vast dehumanisation machine, aimed at the self-determination and individual freedom of black people. From perverse bureaucratic methods like the pencil test down to the uniforms associated with township schools, every aspect of the society was coded to enforce a rigid racial caste system, with Manichean visual dividers between black and white bodies and spaces.

The end of Apartheid in the early 1990s offered to usher in a new era of collective and personal freedom, and to rollback South Africa’s isolation from the rest of the world. But this reintegration took place against the backdrop of two linked world-historical transitions, with profound impacts on individual subjectivity.

Firstly, South Africa’s democratic experiment coincided with triumphant neoliberalism, the ideology which holds that the unrestrained free market and ruthless competition are the best mechanisms for achieving human well-being. Everything, from education to love, is fundamentally a transaction, to be measured and understood in economic terms [3]. This “Atlas Shrugged, winner take all ethos…. Unfettered by any remnant of social contract” has allowed the global rich to accumulate more wealth than at any time in history, their children stunting baroque displays of acquisition on Instagram [4]. Within the wilder culture, there has been the emergence of an obsessive, anxiety-riven individualism, which is reinforced through all visual media. Social media relies on the endless curation of personal image for public consumption, while reality TV promotes brutal struggle between individuals, with both mediums exploiting the inner lives of their participants [5]. In societies where individuals are meant to be freer than ever before, stress and depression are epidemic [6]. People are anxious about precarious employment, or riven with inferiority when comparing their lives to the images of perfect fitness, travel and glamour on Facebook. These images are staged and posed for maximum impact, but the consensual hallucination of social media encourages the belief that they are raw, spontaneous slices of live from people who are happier, more in control and successful than you are. Society is objectively becoming more unequal and unfair for the majority, but our technology encourages the belief that the good life is just a click away- and you are missing out.

This technology is itself a product of the second epochal shakeup- that of the computing revolution which has permeated every aspect of our lives. In a just a few decades, Silicon Valley has become the paradigmatic space of modern capitalism, with its tech giants endlessly championing new apps, automation and ‘disruptive’ inventions. The tech sector, and its cheerleaders in the media, espouse a positivistic view of technology in which every new development leads us one step closer to a consumer utopia of unlimited choice and instant access. Through miniaturisation, we are accustomed to carrying around powerful devices that constantly buzz with bright injunctions to buy, download and share personal information. There is supposedly an app for everything… But Big Technology’s boosterism of a post human future cuts against a reality of class, gender and racial oppression, in which large sections of the world’s poor have limited access to technology. Digital capitalism deepens existing hierarchies, rather than pushing over them, with the poor having staggered access to data streams.

The drive for accumulation and the rapid advancement of informational technology underpin the relentless drive for personal data. At the beginning of this decade, social media was culturally portrayed as an emancipatory force, fuelling the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement. But near the end it bears a grim, reactionary element through its association with various spying scandals, Cambridge Analytica, and the far-right resurgence of Brexit and Donald Trump.

Rather than allowing for a free flow of ideas, the internet allows people to exist in echo chambers of targeted news and advertising which reinforce their hostile world views. To date, YouTube videos and memes have been weaponised in spreading extremist propaganda, but advances in off the shelf visual production could create even more divisive content in future. For example, facial re-enactment software could be used to stage inflammatory and slanderous videos that seem indistinguishable from reality.

At the same time, the scope of political authoritarianism has been dramatically widened by the internet. People now voluntarily give up personal information and visual evidence about their beliefs, activities and movements which police states of the past would have tortured and murdered for. Governments are focused on turning the internet into a force for ubiquitous and participatory surveillance, where the citizenry is enrolled in distributing information. The secretive Silicon Valley company Palantir uses social media to supposedly predict an individual’s chances of committing crime and terror attacks, while urban officials throughout the world are enamoured with the idea of ‘smart cities’ where facial recognition, body tracking and algorithms predicts citizens movements and behaviour. In China, the state is unrolling a social credit system which uses social media and consumer histories to rate a citizen- and determine their access to work, services and movement [7].

Indeed, the individual need for social affirmation and connection is actively operationalised by social media platforms designed to be as addictive as possible. Justin Rosenstein, the engineer of Facebook’s like button, has compared social media to heroin, with users turning to sites to blot out feelings of pain, exhaustion, boredom and misery [8]. Receiving likes and comments on a photo provides a potent, but fleeting buzz of affirmation, and so we keep scrolling and sharing to get another fix, all the while sharing the personal data the platforms feed off. Silicon Valley has essentially created platforms which successfully monetise the unspoken loneliness and frustration of late capitalism, putting their users to work in what are ostensibly recreational spaces, but which in practice are increasingly serving as the centre of many people’s lives [9].

A banal critique of internet culture in general is that it makes people fake by presenting idealised visuals and statements of their lives. But surely wanting to show your best self to the world, or wanting to share your achievements with your friends, are hardly negative desires in themselves. The danger rather is that technologies of visual manipulation and staging emerge against a cultural conjecture where they serve to control us and narrow our understanding of social reality. Instead of wishing for some non-existent past of ‘realism’, we should explore how to liberate technologies to visualise the culture and society we want.

References

[1] James Bridle, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future, Verso, 2018

[2] Simon Sellars and Dan O’Hara (eds), “Introduction” in Extreme Metaphors: Interview with J.G Ballard, 1967-2008. Fourth Estate, 2012

[3] Wendy Brown, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Zone Books, 2017

[4] Mike Davis and Daniel Bertrand- Monk (eds), “Introduction” in Evil Paradises: Dreamworlds of Neoliberalism. New Press, 2007

[5] Mark Fisher and Jeremy Gilbert, Capitalist Realism and Neoliberal Hegemony: A Dialogue. New Formations, 2013

[6] The Institute for Precarious Consciousness, ‘Anxiety, affective struggle and precarity consciousness raising‘. Interface, 2014

[7] Matthew Carney, Leave no dark corner. ABC, 17 September 2018

[8] Paul Lewis, ‘Our minds can be highjacked: the tech insiders who fear a smartphone dystopia‘. The Guardian, 6 October 2017

[9] Marcus Gilroy-Ware, Filling the Void: Emotion, Capitalism and Social Media. Repeater Books, 2017.