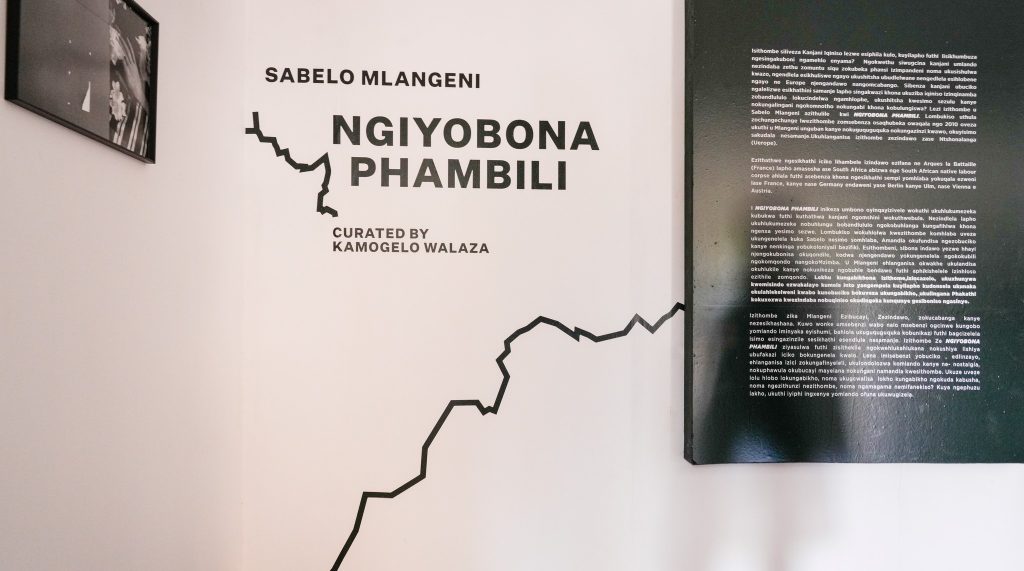

Opening on the 1st of September at Umhlabathi Collective, Ngiyobona Phambili, meaning “I (*will) see ahead,” marked Mlangeni’s return to the South African art scene after six years abroad. Featuring mostly landscape photographs taken between 2010 and 2020, the exhibition uncovered works that had previously languished in the dark—shining light on the lasting impact of trauma on landscapes and the people that inhabit them. It is a spiritual meditation on space and time and photography’s concurrent role—insight into Mlangeni’s confrontation with prejudice during his time in Europe, before his inevitable return to South Africa with this new point of view.

Thembeka Heidi Sincuba: Ngizwa kuthiwa ubungekho iminyaka eyisithupha?!

Sabelo Mlangeni: Ngoba ngezinto zam’ ngihamba phantsi. Ngihamba phantsi.

THS: What motivated you to begin making this body of work?

SM: Uma usubhekisisa kulemnyak’ eyisithupha isiqalo sakhona singaphambili. Mhlambe isiqalo sakhona siyi masterclass—that’s where I got introduced to curators and international photographers. So that’s where I kind of met people that made it connect. And I remember my first residency actually, it was here, at home, in our region, at Lagos. So from that time, I think mangabe ngiyithola leya invitation to come to Lagos, I was in this space where I was like, “I don’t want to leave home. I’m fine here. There’s no war here, no disease—why go?” But I remember having a conversation with a friend who said, “It’s okay uma umunt’ esaqal’ ukuwazi uku sharpenisha iso lakho. Indlela yok’buka. Nendlela yokwenz’ iithombe. … Kwakuyi Paris nge first time ngiye Europe.”

THS: What year was that?

SM: 2012. I was invited by this photographic institution and ngiyakhumbula mangabe ng’fika e airport. Uyafika okok’qal’ abantu bak’linda ngaphandle!

THS: Ehe! Bak’linda-

BOTH: Ngaphandle! (*laughter)

SM: Kanti mina ngafika kwathiwa mawufika uzothath’ is’timela sikuse kwenyindawo, sok’linda khona. Leso bekuyisiqalo sokuthi ube ngaphandle kwasekhaya futhi endaweni lapho kungakhuluny’wa khona ulimi lakho. Lapho oy’thola khona ungaz’ ukuth’ konje mawuphuma ngaphandle uye es’tolo uqala konje uthini kumuntu. Mawufun’ isinkwa, mawufun’ usizo, mawulahlekile. Futhi ngalesos’khath’ besas’nganawo thin’ ama smartphone. Bekufanele ubuze uthi manje “Eh! “Parlez français?” bathi “No English! No English!” It’s like immediately when they’re saying “No English!” they’re pushing you away.

Especially mawusebenza nge camera. Lapho esikhathini esiningi kufaneka ukhulume nabantu ngaphambi kokuthi uthathe iithombe. So, language creates a barrier. And I believe that as much as mangabe sibheka lomsebenzi lo, for example, uyabon’ ukuthi I was interested in time and memory. But also interested in abandonscape, for example. But at the same time I was like, how do I photograph an abandonscape in Europe as an African?

And in a city like Paris—a city that has been photographed by masters! So, it started with this approach I call passerby protestor photography, where I come into a space, and there’s a conversation, and people are protesting, and then the camera becomes my placard. […] So this is how it starts and then it moves to landscape. But then also I’m talking about how it finds its starting point very late, actually in 2016, while the work actually started in 2012. …

THS: That’s fascinating. So, when I look at these images, neh! Like even though I know they’re not here, they feel like here—maybe it’s the space or the way it’s curated. You know what I mean?

SM: (*laughs out loud) Exactly!

THS: So, why do you think that is?

SM: Someone was shocked actually mangim’tshel’ ukuth’ it’s Europe, wayeth’ it’s Bertrams somewhere.

THS: There’s a language there, right?

SM: Yes, yeah. … I like that there’s no marker of time. […] I think that was very intentional … especially once you include this photograph of the portrait, like this one [he directs my attention to a striking portrait of a man in what looks like a construction site], suddenly the image just changes everything—the whole series.

THS: I see that.

SM: There was one work where I focused on photographing day through the lens of night—walking during the day but thinking of night. I think this theme evolved from looking at how other photographers have explored similar ideas over the years. There’s a photographer in Japan who did similar work 60 years ago, and this work is still powerful, you know? How do you make the work not a shade of those images?

That’s exactly the challenge. Even when I started focusing on landscapes, I had to think about what it means for me, as a South African photographer, to photograph European landscapes. It’s a deliberate decision—using landscape as my starting point.

THS: The question of umshin’ wokthwewula arises—if you wrap all these elements around your personal protest in a place where you felt alienated; considering the landscape and how it has been represented, especially in those spaces. Now, with the camera in your hands as a Black man navigating this landscape, the question is: uyabathwebula na? Is that how you’re activating these ideas?

SM: Ngike ngacabang’ ukuthi: does this work in returning the lens in a way? I’m thinking about that a lot. For example, lesitohmbe lesi esingale eglassini—it’s a stolen photograph. It speaks of stolen artifacts in European museums, for instance, this is the Hamburg Forum in Berlin, which is being built to house fashionable wares. Stolen works, yes. Exactly. I’m trying to be democratic. It speaks of how we find it so hard to access archives in these museums—the glass creates this distance. It returns the lens ngendlela enganakho ukuba obvious futhi enganalo udlame.

THS: There’s a haunting quality to your work. This sense resonates with your previous work, which conveys deep spirituality. What’s the role of spirituality in your new work?

SM: It speaks to the concept of time—when you spend the time with the landscape. If you go to a space, it very much holds historical events. These events are very intimate to us. […] The whole process of moving around and thinking before making a photograph, you can sort of think of it as meditation. When you work on long-term work, I always say that you don’t wake up feeling the same every day, there are days where you’re feeling lacking, but also there’s things that affect you spiritually.

THS: There’s something experimental about this, deviating from your established style. What have you learned as an artist? Were there surprising elements about showing this work, and how do you think it has influenced you moving forward?

SM: Ukukhombisa lay’khaya kukodwa. Umangabe lomsebenzi bewukhmbise kweny’ indawo, like a gallery space, there are things ebengeke ngizenze because bengizotshelwa ukuthi no! Kumele ngichaze kahl’ ukuthi why ngifuna ukwenza leyonto leyo. So, ukukhombisa lana kunginikeze inkululeko. That’s the beauty of spaces like this. We don’t have to bend to corporate interests. It’s great to be able, as a group of artists, to put together a program or a show like this—just giving each other support.

THS: As you know more photographers are emerging every year, especially in the city. It’s extremely competitive and sometimes even oversaturated. As a photographer who has made a mark, who is part of the canon so to speak—would you offer specific advice to young photographers?

SM: I think we still need to revisit this canon of photography. There were and still are photographers working in the townships. All doing the same thing—recording time. But they are nowhere to be seen and unfortunately, some archives are being destroyed. […] When was the last time you engaged with the work of Peter Magubane, for example, or of Alfred Khumalo? My own introduction to many of these artists came late, when I studied at Market Photo in ’97, just after apartheid ended and got introduced to people like C.S. Mavuso. These are the people that are supposed to be part of this.

Photographers like Tshepiso Mazibuko—lot of young photographers that are coming out with a new energy. Sometimes it reminds me of 2006, when I was 26-years-old—now sometimes I cry. It’s unbelievable that I’m close to 50!

THS: That’s wild!

SM: But when you look at the future of photography in this country, I always say that we’re blessed that in South Africa we start with a photographic history, which is very unique.

Mlangeni’s Ngiyobona Phambili is something of a photographic manifesto. Its hard exterior is almost a prayer—a chillingly audacious affirmation and refusal to wallow in a painful past. I argue that Mlangeni activates his ‘mshini wok’ thwebula, becoming Umuprofethi—a mediator, guiding those who will be guided with his vision of or for the future, just as an Afrofuturist would challenge historical narratives and envision liberated futures. The Ngiyobona Phambili exhibition at Umhlabathi Collective is extended to October 25, offering more time for further exploration.