For many, the art fair officially opened last night. For others, it’s today, but for the lucky few, art week has already been in full swing, with galleries vying for the viewer’s attention and only the strongest succeeding. Founded by painter Banele Khoza in 2018, BKhz Gallery, which began as a personal studio has triumphantly come to be known for exhibiting both emerging and established talents locally and internationally. But few shows have achieved the anticipation of their current solo exhibition, Athi-Patra Ruga’s Amadoda on the verge (1835 – 2035).

In true BKhz fashion, the gallery walls are painted some new bright hue, this time red, blue and the wall on the far middle side holds chalk sketches calling back to the paintings mounted on said walls. This strategic un-white-cube-ing removes the expectation that the exhibition would in any way perform within any delineated parameters. And yet, as one looks closer at the vibrant oil paintings of varying scales and mounting heights, which include The Clown of Fort Glamorgan and The Crane of Golgotha, the viewer finds the work endearingly traditional.

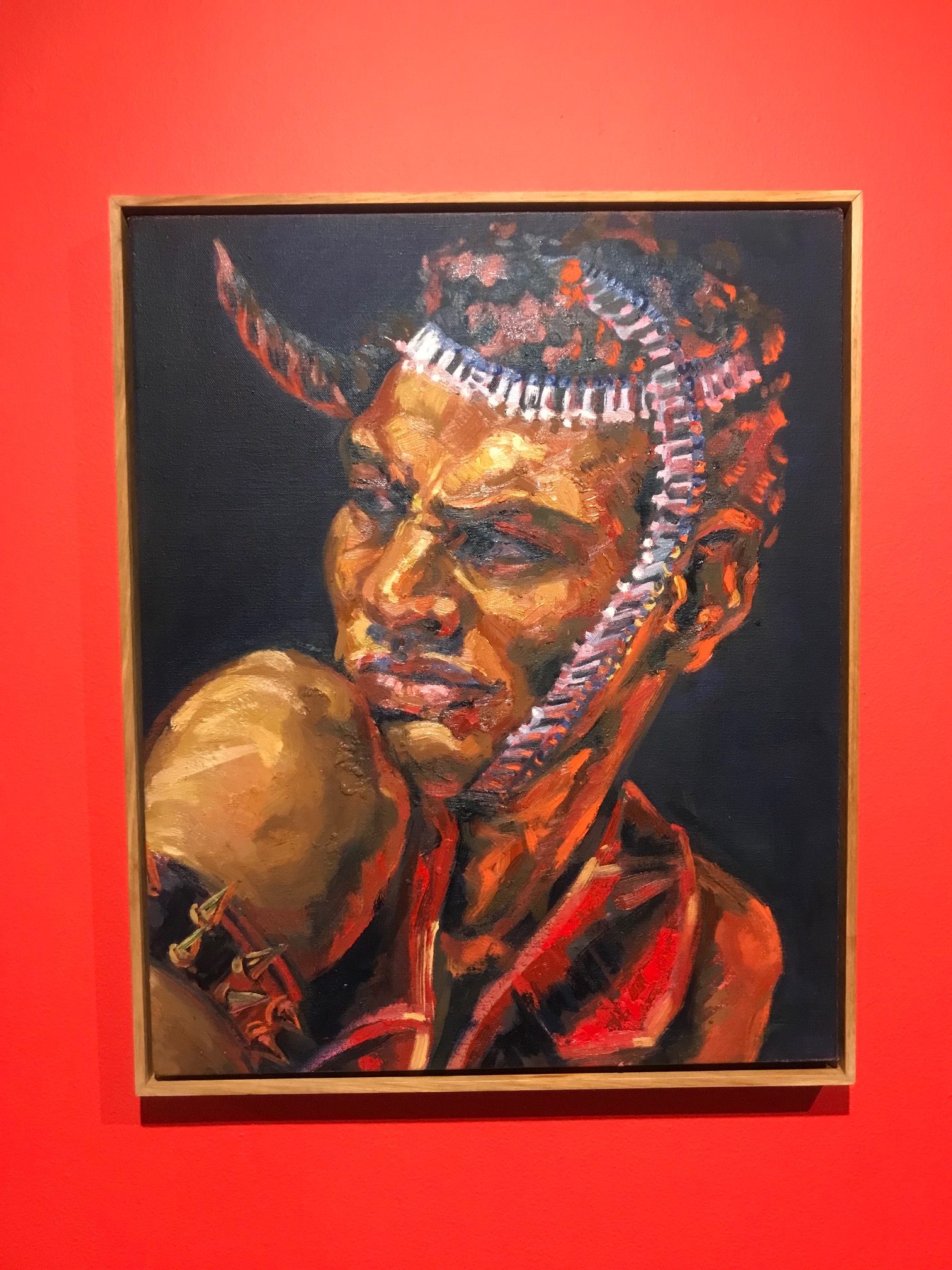

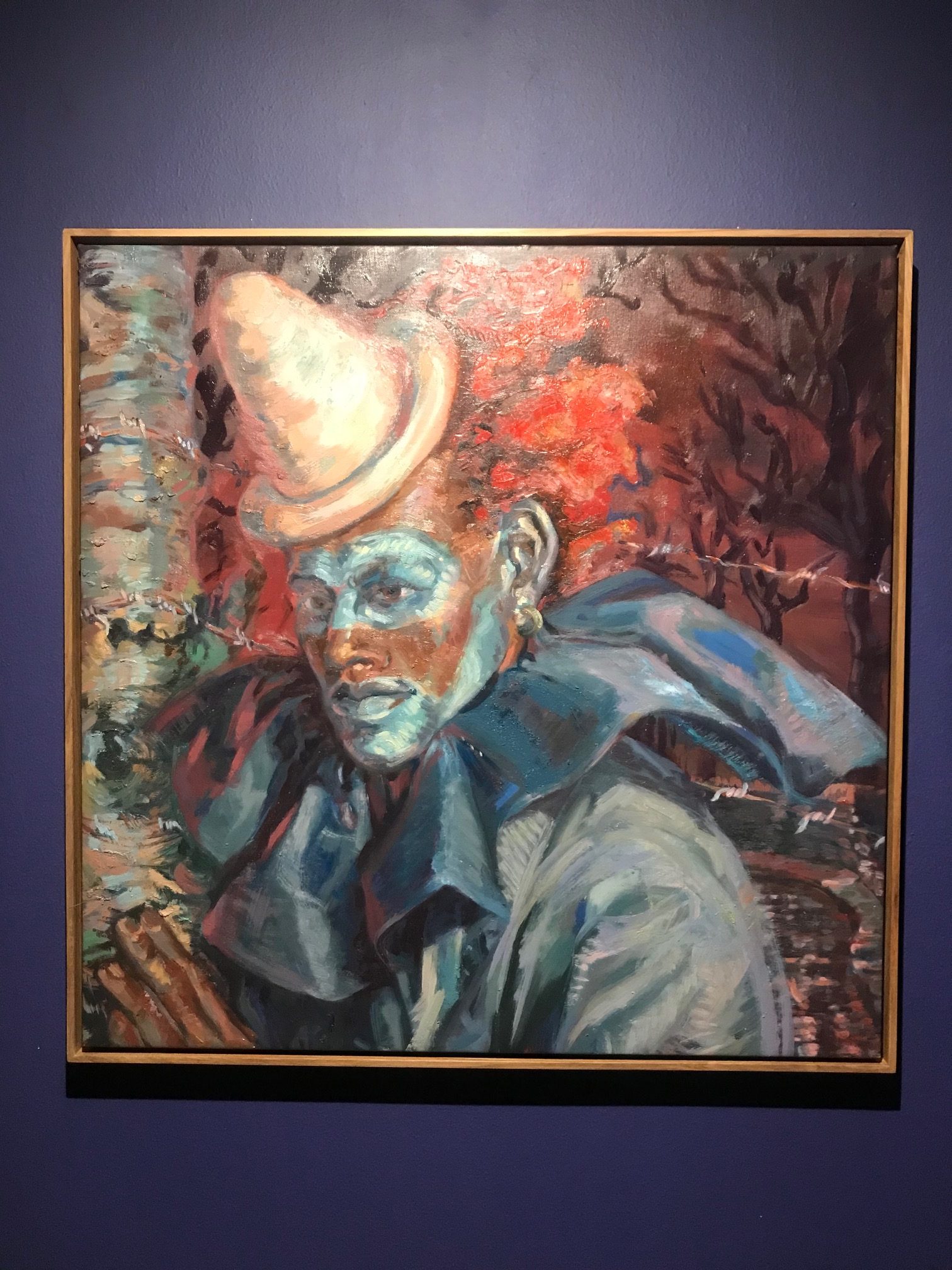

Ruga paints, importantly, clothed figures, in a neo-gothic style and a precarious combination of warm and cool tones—reds, pinks and blues that couldn’t help but be queer. In addition to military regalia, the figures wear feathers, jewels and headdresses. There is playfulness and hybridity here. An evocation of queer traditions of dress-up and of posing that languorously juxtaposes contemporary conceptions of Black masculine subjectivity with painterly conventions of an ever present past.

Eavesdropping on an impromptu walkabout around the BKhz gallery, I heard Ruga say, “The body is a landscape as well, is a frontier. But in this frontier, you’re […] also researching military outfits and their impact on sartorialism in Black masculinity. They would give us hats from the Napoleonic War to be worn like this. […] So there’s this question of agency. Knowing fully well that there’s things that are playing, that are conflicting on your body. And your body is not just a body, it’s a representation of the landscape.

So that’s why it’s starting with the close ones,” Ruga gestured around the room to the intimate group that surrounded him. “It goes to the medium, the studio, hot and dark, or whatever, wonderful backgrounds. And then the landscapes will go wider. But without not putting it front and center. Because if he was just a tiny man, you know, it would be like. This is like every historical painting. You have to pay attention to what’s actually happening. Because his face is this, like, very cinematic thing that I love.”

There is an element of leisure in Riga’s conception of pleasure, where both the portrayal of the subject and the landscapes in this work hark back to olden times. To say nothing of the sexual power dynamics within pre-modernist artists’ studios, the historical practice of painting en plein air, with expensive oils and edgy technology, represents two types of privileged participation with the natural world. On one hand it evokes an epistemtic resonance, where colonial violence has imbued our sense of space and time with racialised mistrust. On the other, an intimate mirroring between artistic ancestries and the almost erotic dialogue with the landscape.

Not only are Ruga’s provocative portraits aesthetically compelling, they are rather seductive in the conceptual sense. The succinct exhibition depicts 19th-century Eastern Cape subjects and landscapes, through Ruga’s revision of settler-colonialism’s impact on Black masculinities. Producing something which straddles the realms of fact and fiction, and positioning his figures simultaneously in spaces of viscous violence that are also beautiful and nostalgic, Amadoda on the Verge, “meaning men on the verge”, assaults the colonial violence of Zwart gevaar, caringly replacing it with the softer, more supple and slippery sides of Black masculinity.

Black male desire and sexuality may have been distorted by the insatiable White gaze, shrouded in questions of history, but Ruga’s images defiantly appeal to a lustful Black gaze, teetering on the threshold of fetishism. Other than appearing amorous and stylish, Ruga’s alluring subjects are also hard and rather rural. Wild in ways one would rather not mention. Hard to look at. Hard to take. To grasp. Even the landscapes that surround them, abstract or otherwise, though somewhat plush in form, are also at moments perplexingly hard, rendered in quick yet cunning strokes. There is something extraordinarily gendered about these gestures. It is manliness except that appears warm and even wet to the touch.

The moment preceding orgasm is an electric suspension of the senses, where everything is furiously focused on the impending release. It’s a fleeting convergence of anticipation and sensation, where the boundaries of self dissolve, and time seems to stretch. In this deliriously dark and liminal space, there is a heightened awareness of the body’s responses and an anxious attachment to the climatic energy just out of reach. This is the type of transcendent torment Ruga’s tasty brush puts the viewer through.

Of course, the pangs of desire pine for that which follows the verge, but these sustained images warn us not to rush toward the summit, but instead guide us toward a non-hierarchical, decentralised experience of pleasure and pre<>post climatic leisure. In Ruga’s Amadoda on the Verge, Black masculinities flirt with suppositions of what oil paint can do or is supposed to do, teasing new positions, while audaciously indulging in the tried and tested, traditional tropes of representation. If you haven’t seen the orgasmic exhibit yet—what are you waiting for? It opened on the 31st August and closes on the 26th of October 2024.

Images captured by Thembeka Heidi Sincuba