In a “post-apartheid” South Africa, sharing the stories of people of colour is necessary to challenge the representation of BIPOC in the archive. But who gets to create this archive? And more importantly, who gets to dictate the narrative of this archive? These are all questions photographer Tshepiso Mazibuko’s work contends with.

Born and raised in Thokoza, Gauteng, Mazibuko came from a big family where she was expected to support her family. So, Tshepiso never imagined pursuing a career in photography. However, when she joined the Of Soul and Joy Photo Project, a programme that focuses on developing the artistic skills of students in the field of photography from townships, she became immersed in the world of photography and all the promises she believed it to hold.

“I remember, quite naively, thinking that photography had the power to change the world,” she remarks. And while her many years of pursuing this career have taught her otherwise, she recognises photography’s importance in sharing the stories and voices of people left out of the archive.

She began photographing the people and landscape of the township she grew up in as part of the pressure she felt to add to the archive of black bodies. Her first body of work was titled Encounters, where she took photos of people in their homes, exploring the need for belonging and the concept of home and how people relate to the camera, specifically in intimate spaces.

After completing the programme at Of Soul and Joy Photo Project, she joined the Market Photo Workshop on a scholarship she received during her studies. It was here that Mazibuko found her creative voice. Engaging with the poetic and philosophical aspect of photography, Mazibuko explains that photography is not just what you see, “but what it represents and how it makes you feel.” She notes the emotional power photographs hold, and the way the same image can have a different effect on people. “It no longer becomes just you looking at the images, but the images look back at you, almost as though these photographs possess a life of their own,” Mazibuko says.

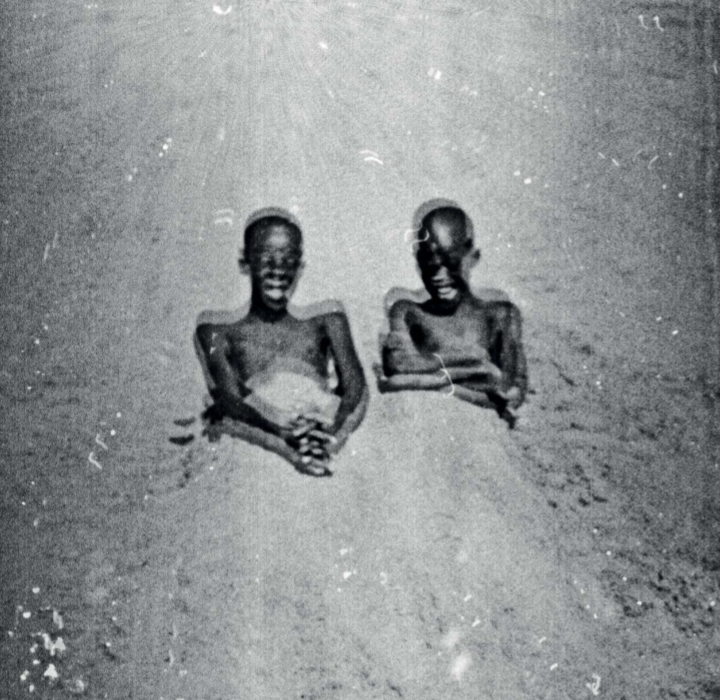

Being a part of the “born free” generation, Mazibuko explains the constant struggle of feeling ‘free’, while still having the weight of generations of trauma and poverty obstruct her access to opportunities. And so, she started her second collection, titled, Ho tshepa ntshepedi ya bontshepe, which translates as “to believe in something that doesn’t exist”. Here she began drawing from the archive and taking photographs of the township, as a way of engaging in a dialogue with the archive, showing the similarities and changes over time.

“I don’t think of myself so much as a photographer but rather as a storyteller,” she explains. In recognising her own subjective gaze, her images engage in a dialogue with the photographic ‘subject’.

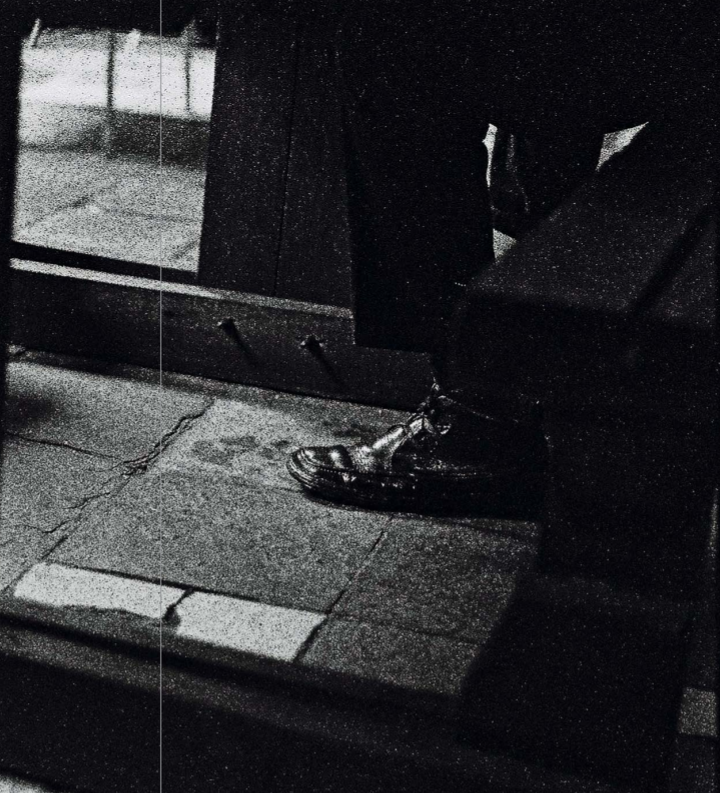

She grew more conscious of her role in creating an archive of Black bodies and started taking photographs in black and white film to remove the element of time. For her latest body of work, Awukho umdlalo ongena’babukeli, translating to “there is no game that has no spectators”, she experimented with expired film. While it started off as a mistake, she found the expired film added an eerie, ghostly effect to the photographs, and felt as though she were adding her voice to the archive.

“There is no one truth,” Maziboku explains of the single story the archive presents, “but this way, I get to narrate the archive.”

Mazibuko lives and practices in Thokoza where she currently teaches visual literacy at Of Soul and Joy Photo Project. Mazibuko is part of the UMHLABATHI collective, which is an all-inclusive hub for creatives that seeks to foster a community of practitioners conducting research in the archive, publishing and photography practices. Several of the photographers part of this collective are alumni of Market Photo Workshop, and includes the likes of Jabulani Dlamini, Andile Komanisi, and Lebohang Kganye among others.