In July this year, I went to see a group show at blank projects called, The weight of a stone. The first thing I saw was a small bundle of red, suspended in the middle of the room. It was tied with a rope that stretched across the length of the gallery, connecting to a pulley, and anchored to a concrete block. My first instinct – probably informed by the title of the show – was to test the weight of the red bundle. It was light and, I discovered, filled with sea salt. My second instinct was to pull the rope. It felt even lighter; if I didn’t watch it bob up and down in space, I would doubt it was there at all.

When I read its title, A Pound of Flesh, the work struck a sinister note. The rope and the sea salt suddenly recalled the trade of human flesh known to us as slavery, the scars of which are felt the world over, but perhaps most palpably on both sides of the African coast. I thought about the insidious ideology that turned people into commodities – into countable numbers, expendable numbers – and the persistence of that logic whenever we prefer to think of ‘others’ in terms of statistics. I thought about the very act of ‘measurement’ as a strategy used by colonists not only to enact violence but to disguise it: when the focus shifts to acres won and profit accrued, few care to bother about the bodies buried to get there. All at once, that little bundle began to look very heavy; its red took on the pallor of blood.

This is what Inga Somdyala does, I think: he takes an object that is simple enough – a bundle, some salt, a rope – and imbues them with such symbolic weight so as to floor you.

A couple of months later, I encounter the red bundle again. This time, there are many of them, stacked symmetrically in a pile in the middle of the main gallery at WHATIFTHEWORLD. I’m at the opening of Somdyala’s debut solo show, ADAMAH, curated by Heinrich Groenewald and Shona van der Merwe of Reservoir. When I asked the curators what struck them about Somdyala’s work, they said, “Something about the term ‘phrasing’ feels applicable to describe it, the way a movement expert might use it to talk about the combinations of gesture, symmetry, and fluidity. Inga has beautiful phrasing, both in his work and his manners.” Indeed, phrasing is something that excites Somdyala. ADAMAH is a Biblical Hebrew word that means ground or earth. It is how Adam of the Book of Genesis got his name. Adam, which literally means red, who was made of the clay-red earth. It is a name that, at once, connects the spirit world and the word of the soil and compresses it in man.

Somdyala is preoccupied with soil. The twelve central paintings of this exhibition are made with a combination of ochre, clay, red oxide, compost, soil and rocks on canvas. The soil is sourced from the Karoo and Somdyala’s hometown, a township outside Komani (Queenstown) in the Eastern Cape. That they immediately remind me of satellite images of earth – or, to go from the macro to the micro, sedimentary samples in petri dishes – is not a coincidence. They are tactile. They are textured. They are, in the most literal sense, landscapes. “It’s not abstract,” says Somdyala. “It’s literal. It’s not an attempt to represent the landscape. I want to see it, to touch it. I want to spend time with it.

I think about what it means to be soiled. In the English language, since the 13th century, to be soiled has meant “to be defiled or polluted with sin.” There is a connection, I reckon, between this fear of dirt and the need to control it, the desire to exploit it – a reckless abandon when it comes to issues of land that manifested as much in the colonial era as it does in our ecologically destructive present. I am reminded of Mary Douglas who, in her 1966 book Purity and Danger, writes, “There is no such thing as absolute dirt: it exists in the eye of the beholder. If we shun dirt, it is not because of craven fear, still less dread of holy terror. Nor do our ideas about disease account for the range of our behaviour in cleaning or avoiding dirt. Dirt offends against order.” Somdyala’s gift is that he is willing to get close to the dirt, to spend time with the dirt, to listen and to learn from the dirt. To dig in, as it were. And, as my colleague at ArtThrob Vusumzi Nkomo pointed out, the act of digging in this context is an invitation to examine the anti-Black logics that constitute the subsurface of Modernity. In other words, those in power get to rise above the dirt, while the oppressed are cast down to it, to toil and – at worst – to die.

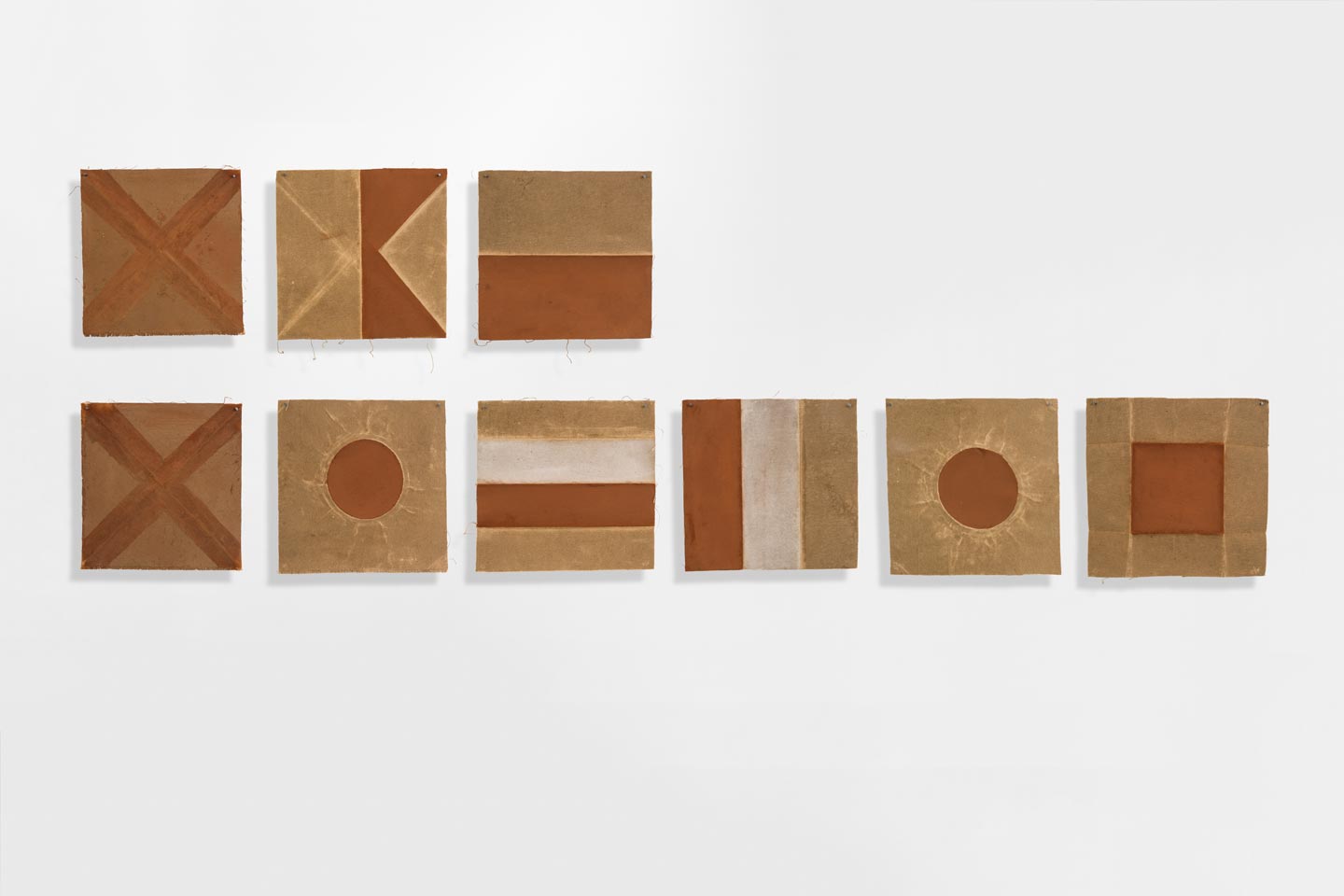

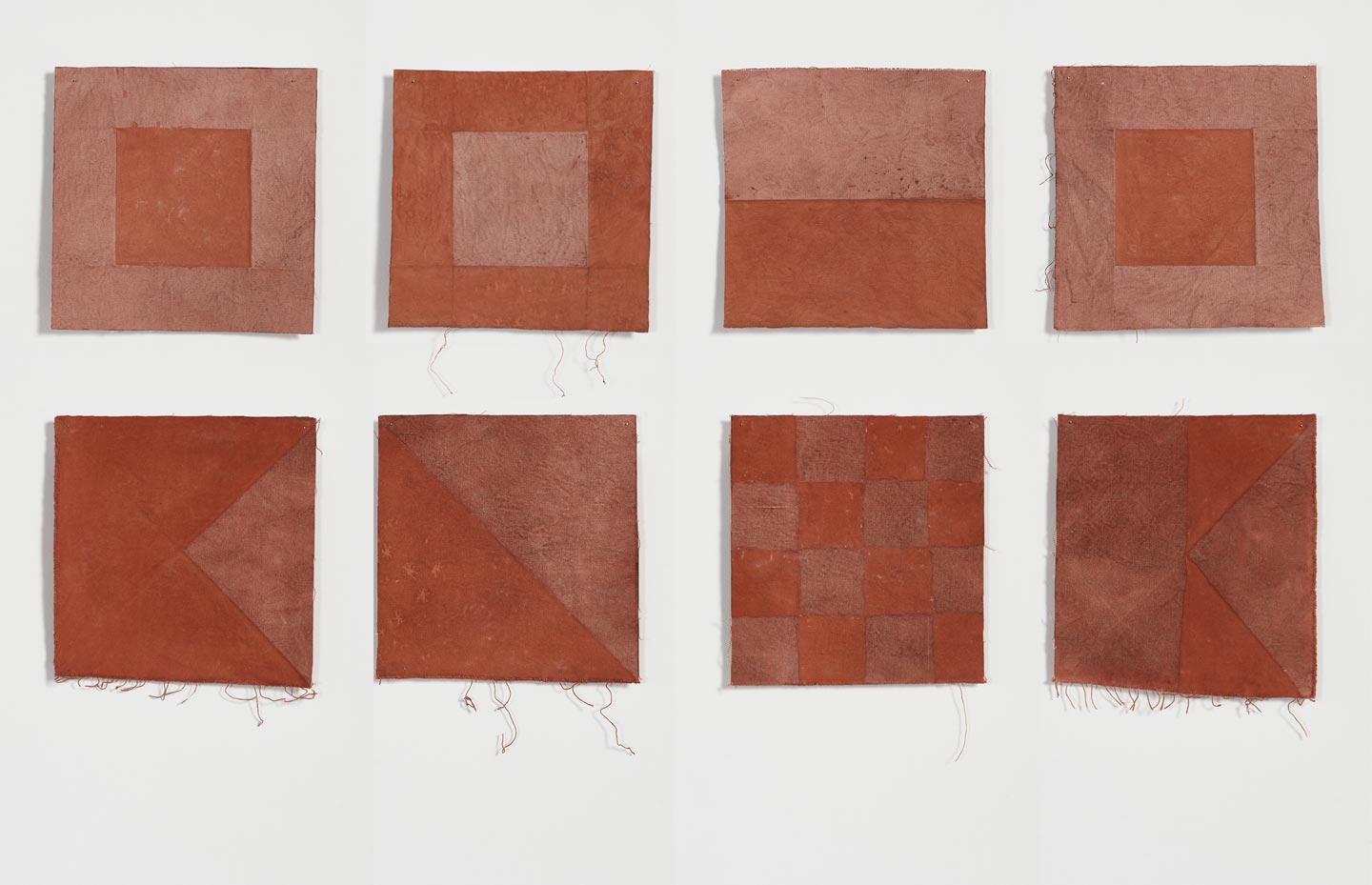

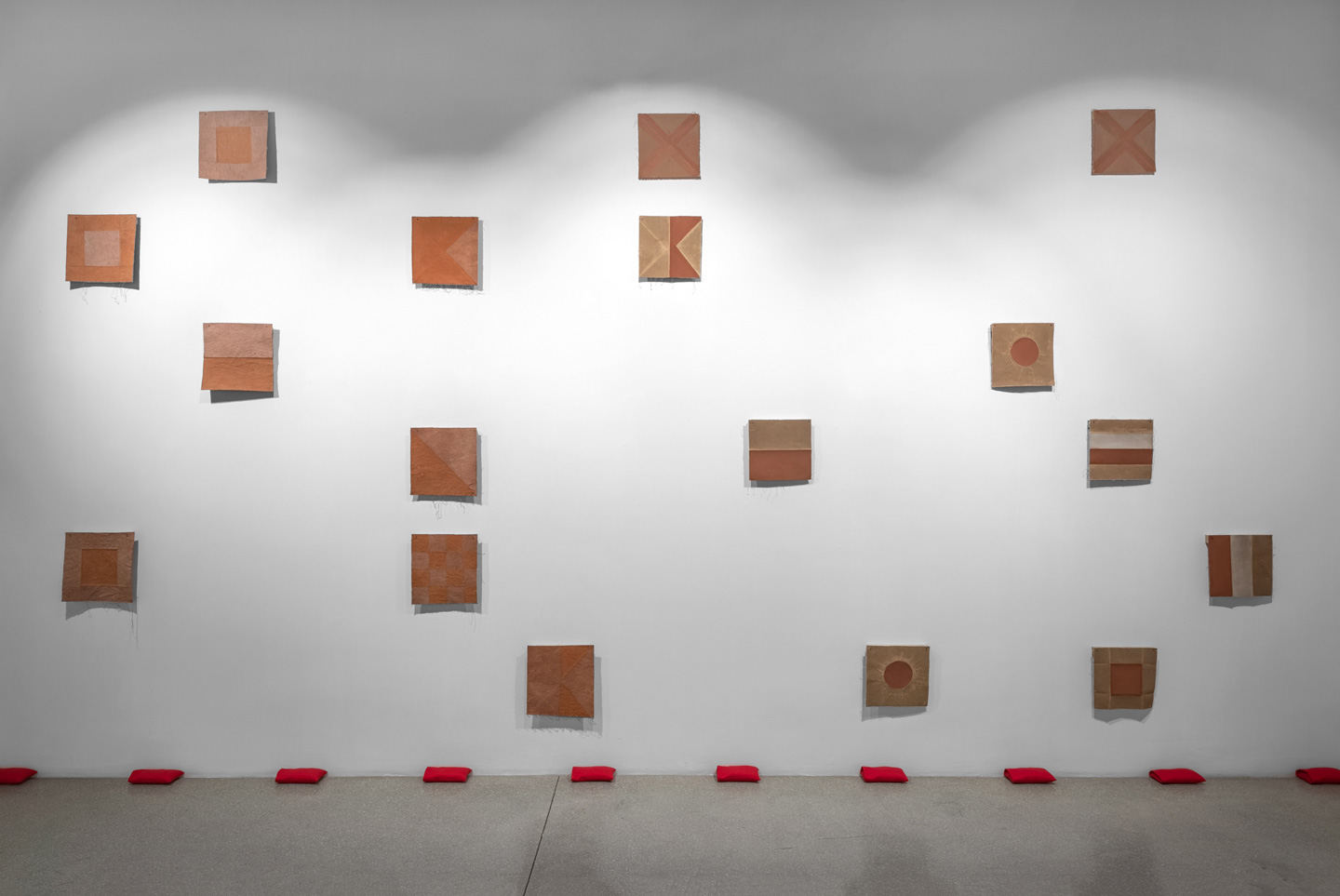

The flag probably is the ultimate symbol of the imposition of power over dirt. On the wall opposite the landscapes, Somdyala has made 27 of them. They are based on an Afrikaner nationalist flag that was intermittently circulated throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Known as the vierkleur, it contains the blue, white and red panels of the Dutch flag and adds a strip of green. When the oranje, blanje, blou flag was adopted in 1928, the vierkleur came to be used as a symbol of far-right groups, such as the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging. Somdyala became interested in these flags when he discovered that its shades of red, blue, white and green are the same shades used in the South African flag post-1994 – an apt metaphor for a reshuffled society, rather than a society revolutionised.

The purpose of a flag – especially when it is a national flag – is to impose unity across difference and to reflect the omnipotence of the state. As such, it is essential that the flag be invariable; there are laws on the books of every nation that enforce uniformity in design, colour and orientation. Not Somdyala’s. His are made with ash or oxide on top of ochre on canvas. Together, these materials undergo various chemical reactions that make the final product difficult to predict. Each flag is entirely unique. A flag by Somdyala has the opposite ideology of a regular flag. It is subject to change, ambivalent to disorder, vulnerable to decay. The artist says he wants to push against “sense of purity (cultural, racial, social).” He is distrustful of that which is supposed to be resolved or cohesive. He wants to “embrace those impurities.”

When I visit him in his Woodstock studio, Somdyala tells me about his fascination with alchemical processes. The ones that play out on his canvases, yes. But also the lesser-noticed ones. Like the magazines in your grandmother’s bathroom that crinkle and warp from the shower’s humidity. Or black t-shirts that develop a red fuzz when they are blasted too often by sun. These days, wherever he travels, he takes a few canvases to bury. He doesn’t plan on digging them back up until fifty years have past, maybe a hundred – maybe after he’s dead. “Let them be forgotten. Let them age. Let them decompose. Let them experience rain and sun.” What matters is that they spend as much time in the ground as possible. “It’s critical to spend time,” he says, because only in time can you “fully apprehend this complexity.”

When he says this, I am reminded of my favourite artwork from ADAMAH. Titled (As Long As I Am Alive) You Will Be Remembered, it is a pair of Nike Stefan Janowski sneakers, tacked high up on the wall. The soles of the shoes are dirty – the midsoles stained the colour of earth, the same colour as some of the paintings. They were the shoes Somdyala wore when his grandmother was buried in 2019. The soil that coats them like a red film is the soil of his grandmother’s grave. Somdyala knows this for sure because – after he helped dig out the site that the gravediggers left too narrow – he immediately put them in a plastic bag and forgot about them until he happened upon them while moving house, just weeks before the opening of his show.

“What better way to preserve my grandmother’s memory and our umbilical connection to that place, than to retire these shoes in favour of this tactile confluence of body and land; of dust to dust,” says Somdyala. “When I found them during the build-up to the show, the timing just struck me as an entirely divine intervention.”

Divine intervention. I think about another Nike – the Nike, the Roman Messenger God. I think Somdyala might be a messenger too, here to carry messages between the underworld, the heavens, and earth. For him, the underworld is the soil. The heavens, soul. And earth is the place where one’s sole happens to get dirty. Being the messenger, he’s not here to lecture us. He’s not even really here to represent or describe. He’s here to tell us to give pause, to pay attention to the messages all around us. As he puts it, we need to “slow down long enough to hear and receive.”