Curating an exhibition, especially one as layered as Ngiyobona (sometimes *Ngiyabona) Phambili by Sabelo Mlangeni at Umhlabathi Collective, is as much a conversation as it is a craft. During a one on one walkabout with Kamogelo Walaza, the curator of the show, I encountered not only the logistical intricacies behind the exhibit but also reflections on artistic practice, spatial dynamics, and what it means to curate photographic works that have previously existed in the margins. What followed was a revelation of trust, negotiation, and renewal—an intimate communion between artist and curator.

The curatorial process toward Ngiyobona Phambili began in a seemingly casual encounter between the curator and Mlangeni earlier this year. “He approached me in February,” the curator recalls, “during an event at the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG).” This moment set the foundation for what would become a deeply personal collaboration. “He told me he had these works, hidden and absent, that he’d created over the years since 2012 through various residencies—works that hadn’t really been exhibited in South Africa.”

While the works were not new, they represented a departure from Mlangeni’s more recognizable visual language, which centers on storytelling through portraiture. Presenting these landscapes and geographical meditations required an open-minded approach: “There’s always a risk when you show something unfamiliar. People get used to a particular voice in fine art. Exhibiting unseen works requires courage, both for the artist and the institution.”

Like many artists, Mlangeni operates according to his own rhythm, which initially challenged the curator’s structured process. “He disappeared for a while, and I thought the show was off,” the curator recalls, laughing. “I continued with my life. I mean, you can’t chase after an artist. But then he came back, and we picked it up again. We had to work quickly—six weeks in total.”

Rather than forcing the exhibition into rigid timelines, Walaza leaned into conversation as a way of co-creating the layout. “I’m the type of curator who needs dialogue to understand the work. I don’t just put things on the wall to make them look aesthetically pleasing. Each meeting—whether we were in the frame shop or sourcing materials—was a way to uncover the story behind the art.”

One of the exhibition’s most deliberate curatorial choices centered on the introduction of color to the gallery. “Sabelo wanted to introduce green and gray into the space,” the curator explains, adding that this decision was grounded in both symbolism and lived experience. “The gray represents a kind of gloom—how it feels to be a Black man in Europe, constantly navigating stifling stereotypes. But green represents renewal. Even though the works explore heavy themes, there’s also an underlying sense of rebirth. This is Mlangeni’s chance to show something new, something hidden.”

The spatial layout reflects the same intentionality. “I structured the works to mimic the ebb and flow of landscapes,” the curator notes. “Nothing is strictly at eye level or arranged in a predictable salon style. It’s about movement—just like with landscapes, you can choose to step closer or pull back to see the whole picture.”

The disjointed lines scattered across the space also carry meaning. “The lines aren’t continuous, just as Sabelo’s experience in Europe wasn’t seamless. It reflects how disjointed life can feel when you’re navigating spaces not made for you.” Beyond the visual elements, sound plays a crucial role in the exhibition. Visitors encounter audio recordings of Mlangeni recounting moments of racial profiling in Europe. To create an environment where visitors could fully engage with these stories, the curator drew inspiration from photography’s darkroom.

On the far end of the exhibition is a room filled with black and white portraits, dim and lit only by a red light reminiscent of a dark room. Overhead is audio of the artist himself in the clutches of a rather intimate retelling of a story almost too wrenching to recount. “In a darkroom, you need focus—it’s where negatives are transformed into positives,” the curator says. “I wanted the gallery to evoke that same sense of concentration. The audio sets the tone, demanding reflection.” Objectively, this tactic was effective.

Walaza made some other impressive curatorial choices, namely paying particular attention to the senses and the sensual in an otherwise hard show. “I even introduced red lighting elements to mimic the atmosphere of a darkroom, heightening the intimacy,” says the curator. … “ ’cause this is performance art as well. Like, soundscape is performance art. I feel like even in the act of walking and listening to the audio, the audio itself becomes a performance. I don’t know if you feel the same way, but yeah… you want to listen to the audio.”

In a way, language became an extension of that curatorial tenderness. “I came up with the idea that it would be really cool if we had Zulu translations. […] I feel like, when people come in, they should see how his mind works. You probably dream in Zulu, you think in Zulu, and you know how to write in it. So, why not translate it into English or any other language too? And I think, during that conversation with Dr Kholeka Shange, she also spoke in Zulu. I asked her to speak freely in the way she felt comfortable. Not just because it’s Zulu, but because that’s how she naturally expresses herself.”

While the curator brought her own vision to the show, she emphasized the importance of meeting Mlangeni’s needs. “A solo exhibition isn’t about imposing your vision. It’s about making the artist feel comfortable and heard. I had to adjust my process to fit his, even when it meant embracing unexpected elements like color. Sabelo wanted additional walls, and I agreed, but I also added a few more. We needed the space to work with us, not against us.”

For the curator, the goal was not to fill every corner but to allow room for the works to breathe. “When you think about landscapes, they aren’t cluttered. They require space for contemplation. That’s the feeling I aimed to create.”

Ngiyobona Phambili is an example of layered curation, which has brought us into close contact with long-overlooked works by a treasured photog. Central to the curation process was an exploration of the artist’s time in Europe, grappling with racial prejudice, but also his return home with a new purpose. Events like Dr. Kholeka Shange’s talk and discussions on September 7, as well as Modise Sekgothe’s walkabout and performance on September 28, deepened these explorations. No longer ending on October 5, the exhibit has been extended to the 25th.

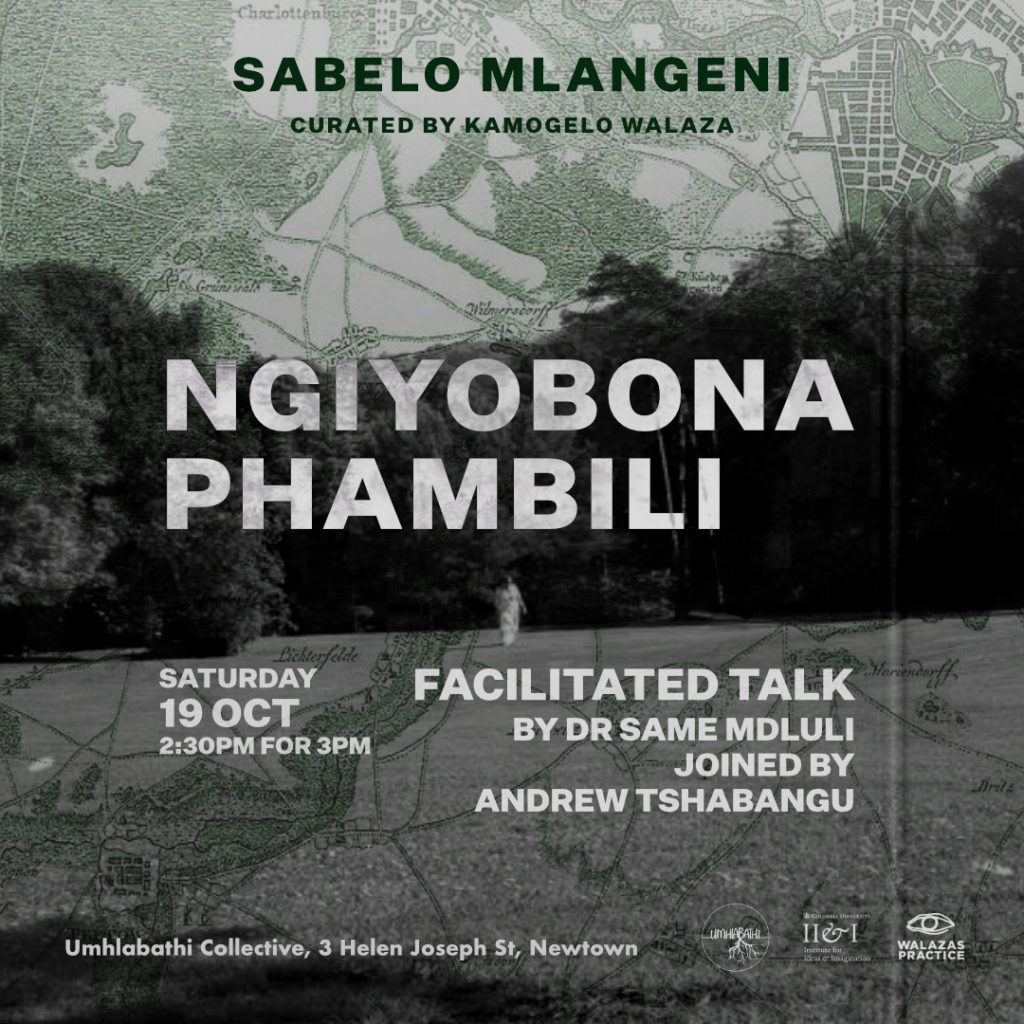

Don’t miss out on the late afternoon wine and drinks event centered on Ngiyobona Phambili, happening on the 19th of October at 2:30pm for 3pm. A conversation will be facilitated by Dr. Same Mdluli, focusing on Sabelo Mlangeni’s landscape photography and Kamogelo Walaza‘s curatorial approach, with participation from Andrew Tshabangu.