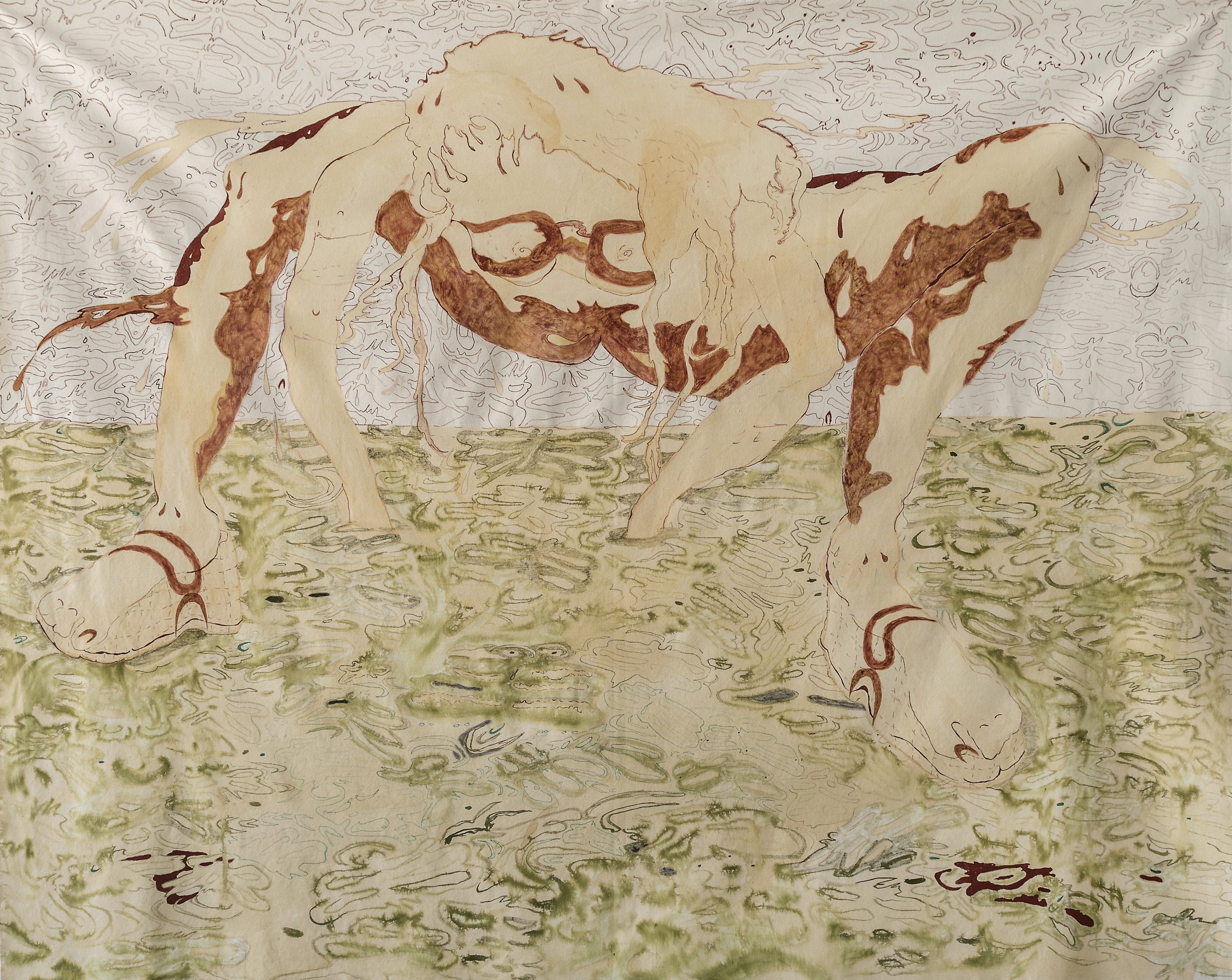

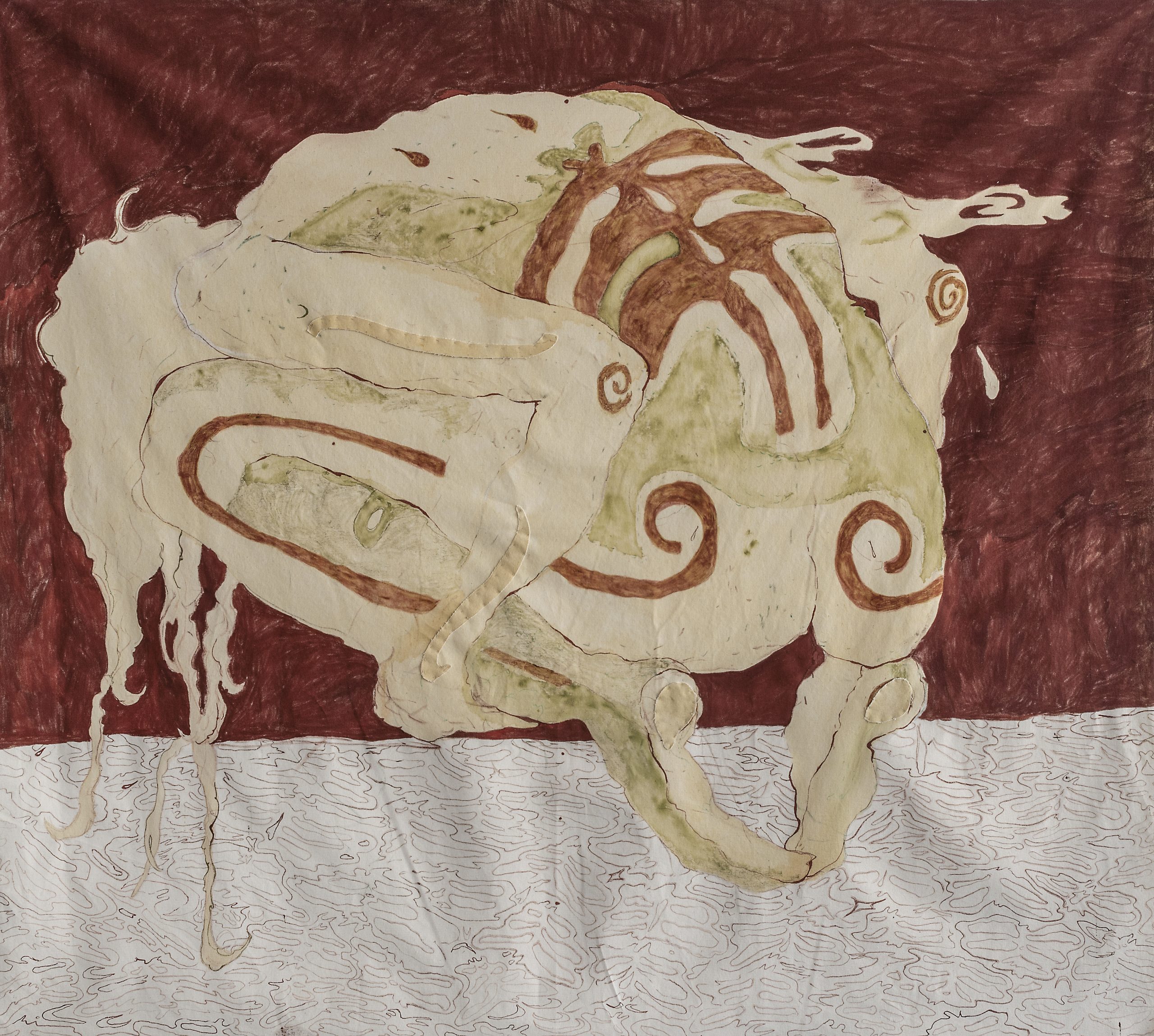

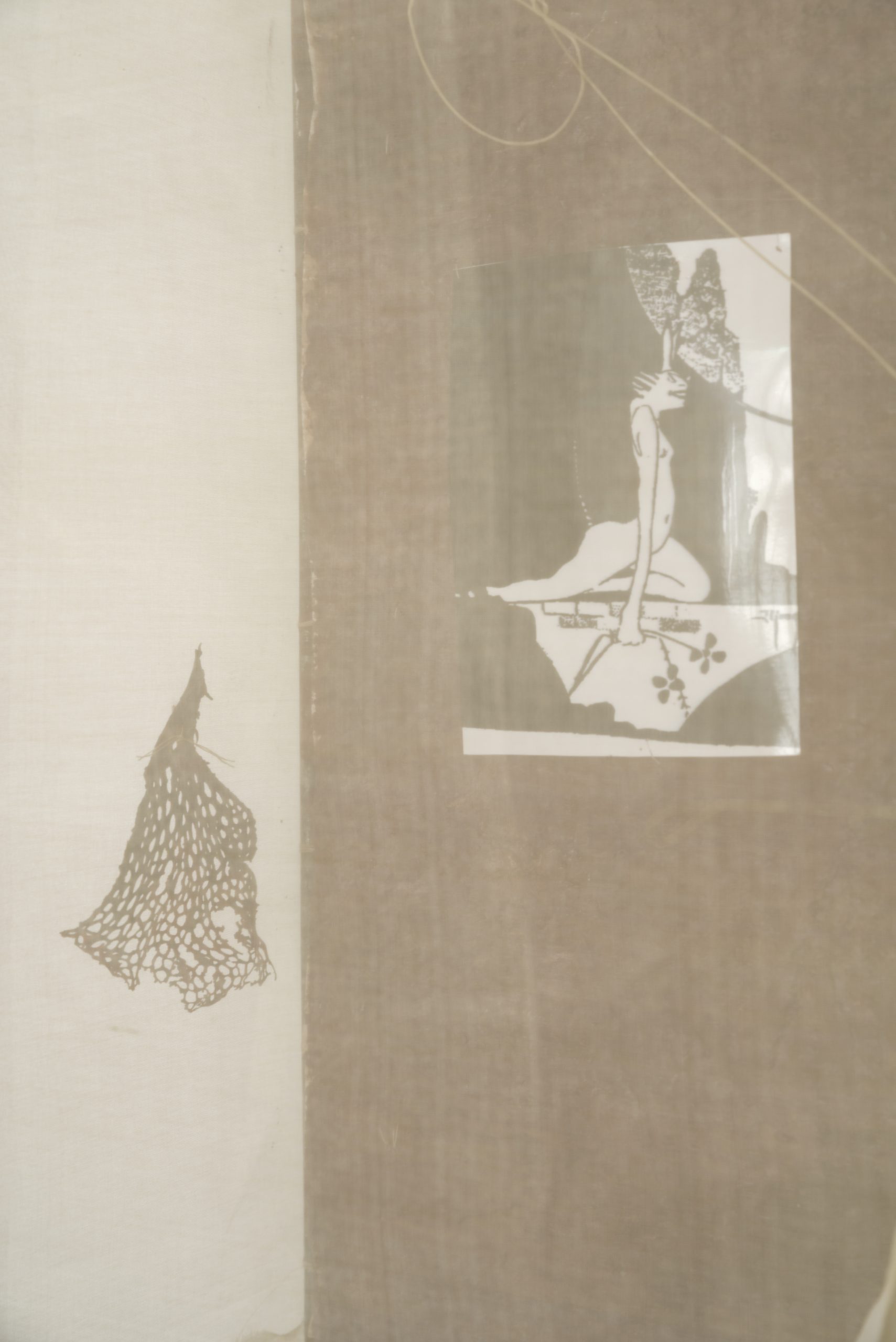

The chemical ecology of poisonous butterflies brings to question our reliance on nature for beauty, as we romanticise planetary mechanisms as a refuge from our own inorganic decay under industrialisation, precisely undermined by the fact that Nature is often expressed even in all its putrid glory; our own bodies being eco-systems of bile, pus and decomposition. Silken expressions of Antonia Brown’s sculptures remind me of the toxicology of poisonous creatures in this regard. The structures — at first glance — are inviting in a range of earthen taupe hues. However, on closer inspection, there is something seemingly grotesque about the subtle contortions of metal and fabric. Contrasted against Jeanne Gaigher’s elusive ink figures, I realise there is a stark symbiosis between the works — whether intentional or not. As the figures wither inwards across the canvas, their backs expose a sense of trauma and pain, and when I glance — searching for parallels between the sculptures and painting — I see the threads signalling at the binding nature of nature.

Considering the metamorphosis of butterflies from larvae into the gracious symbols of our cultural lexicon, in viewing the works, I wonder why my mind keeps leading my thoughts back to these winged beings as a reference to the pieces? Perhaps, it is because they undergo immense destruction to be born again, entirely anew? Out of a chrysalis, bodies cracked and broken open, wings emerge and the transformation from inertia to flying occurs. This seems deeply poetic, but while I consider this in the studio room, I realise how terribly disturbing nature is — illustrated by the pre-chrysalis phase of Antonia and Jeanne’s works, in which the final flight has not been taken, and what is shown is the descent of physicality into discomfort. I see this offering — and revelation — from both artists as a stunning insight into the ability for art to communicate all phases and passages of experience; assured that we cannot hide from the harrowing verities of the natural order.