I consider myself as a feminist, a Black feminist. A feminist that works within the South African context—a feminist that works also works within the continent because I am African before I become South African it’s something that I knowledge everyday, that my story is not completely different umm to the rest of the women that live on the continent. Yes I am, my work is entirely about the position of Black women; it’s entirely questioning that position. Positions that I choose to take and positions that not to take as a Black women.

This is Senzeni Mthwakazi Marasela speaking about the explorative space of her work. Waiting for Gebane, her latest solo at Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa explores women in different states of waiting, a state which “can be caused by several factors that force loved ones to be apart, factors such as war, the search for work and greener pastures. For Marasela, waiting becomes more than a matter of physical separation—it is experienced with mixed emotions such as anguish and anticipation.” So skipping down this line of thought, I think of waiting as saying something about the future or possible futures, about desire, aspiration and the hopes and fears threaded through this state of ambivalence. Waiting as a holding-ones-breath-to-exhale space. Waiting as revealing something about the politics of justice, freedom and access. I think of who in this country spends most of their time—culminating into life—waiting. In taxi rank lines, public hospital lines, NAFSAS lines, waiting for a delayed promise, waiting on deliverance.

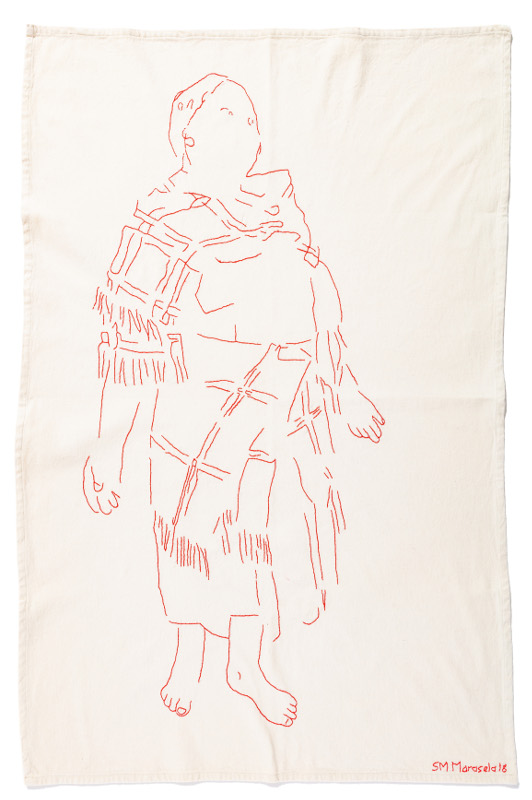

Working almost exclusively in red through textiles, embroidery, photography and painting; Marasela traces this personal and collective experience of womanhood using Theodorah Mthetyane her performance fictional alter ego. “I continue to wait in different conditions as a Black women don’t I? I wait to accept my body, to accept my voice, to accept what I think, to accept that I need to position it myself”, shares Marasela talking through the ideas explored in the solo. Theodorah’s story of waiting is rooted in Apartheid and Johannesburg’s H/history of migrant labour systems when her husband:

leaves her in the rural town of Mvenyane in the Eastern Cape to look for work in Johannesburg, he gives her an ishweshwe dress. In Xhosa culture, this garment signifies her married life. Theodorah holds onto this dress, wearing it every day to show her faithfulness to her husband. When he does not return after many years, Theodorah leaves home to search for him.

Marasela begins the journey of tracing this personal and collective experience of womanhood her grandmother’s generation, documenting the period of ‘red dust’ from the early 1900s, when Black daily life in South Africa was characterised by disruption and conflict. The red dust refers to a period of severe drought; kicked up by the movement of horses and people—that of Black men from the rural areas of South Africa, who were conscripted to fight in the Second World War or were sent to work in the gold mines of Johannesburg. It can also be linked to the red mine hills of industrialised cities like Joburg, which serve as proof of their labour. In Marasela’s work, red is a bold marker of Black life during these times, which has been historically misrepresented, omitted, or censored. Marasela uses the historical materials of ishweshwe and Kaffir linen[1], as well as the process of photomontage, to produce fictionalised stories of the red dust period. This creates an extended series of images which realise and represent daily Black life. Theodorah waits but in realising that he is not coming back, she [takes] a decisive action to search for Gebane in the city. There, Theodorah observes the brutality of urban life in the streets…she witnesses homelessness, people waiting in queues on the streets and police violence against the poor. However, Marasela’s show doesn’t just colour the condition of waiting in hues of negative feeling, through her exploration she also recuperates waiting as a state of potential resistive forward action:

highlighting a will and determination which resists the idea of waiting as a postponement of life, and the erasure or invisibility of women. Theodorah does not wait for justice or liberation. Through her performed hyper visibility, she reclaims the ‘unrecoverable’ years.

[1] Marasela’s decision to retain the use of the derogatory, racist word is to hold onto links to the cloth’s racialised and cultural history. Given to prisoners in the form of blankets, it was also used in domestic environments for curtaining and is used to make dresses worn in Xhosa cultural rituals. The cloth is also linked to mythological stories of Xhosa Kings.