Brünn Kramer’s Master of Fine Arts exhibition, Tronkvoël, opened at the RAW Spot Gallery of the Arts of Africa and Global Souths research programme in the Department of Fine Arts, at the University currently known as Rhodes in Makhanda on 12 March 2021.

From 08 – 29 August 2021, the show which utilised the visual language of South African prison culture as a metaphor for experiences of depression, was featured at the RK Contemporary gallery in Riebeek Kasteel in the Western Cape as Kramer’s first solo show.

In this conversation, arts writer Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti caught up with Kramer to talk about the work and both shows.

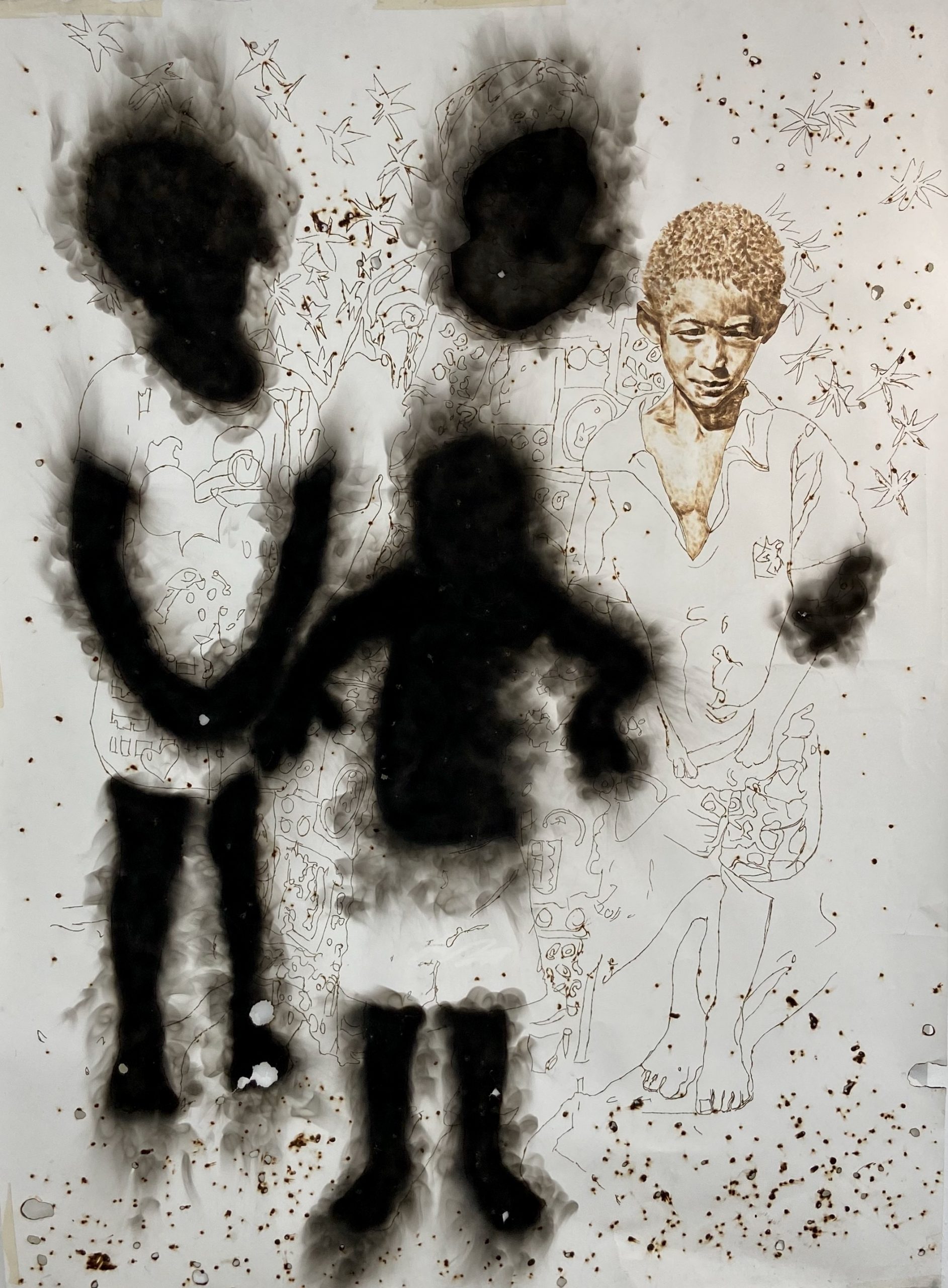

Die Mal Kind. 2020.

Firstly, congratulations on your MFA show and your first solo exhibition. Maybe you can start by unpacking the title of your work.

Brünn Kramer (BK): Tronkvoël (Jailbird) is a convicted felon that keeps on returning to prison, a recidivist. Prisoners, even after serving their sentences and being rehabilitated are stigmatized and ostracised by society. People who suffer from any mental illness suffer the same prejudice.

More so, the title alludes to the core theme of my research in which my experiences with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) can feel like an invisible and self-constructed prison. The work thus engages with the idea of prison as a metaphor for depression. It developed out of earlier work that centered prisons and ex-prisoners.

I read the metaphor of a prison in several ways, most of them translating to a life without happiness or anything to look forward to.

Would you please elaborate on this notion?

BK: The implication is that society views prisoners as inhumane, not worthy of affirmation, even after they are released from prison. Prisoners endure this stigma through systematic dehumanization, marginalisation, and restrictions on their human rights. What is worse than to be seen and feel like absolutely nothing?

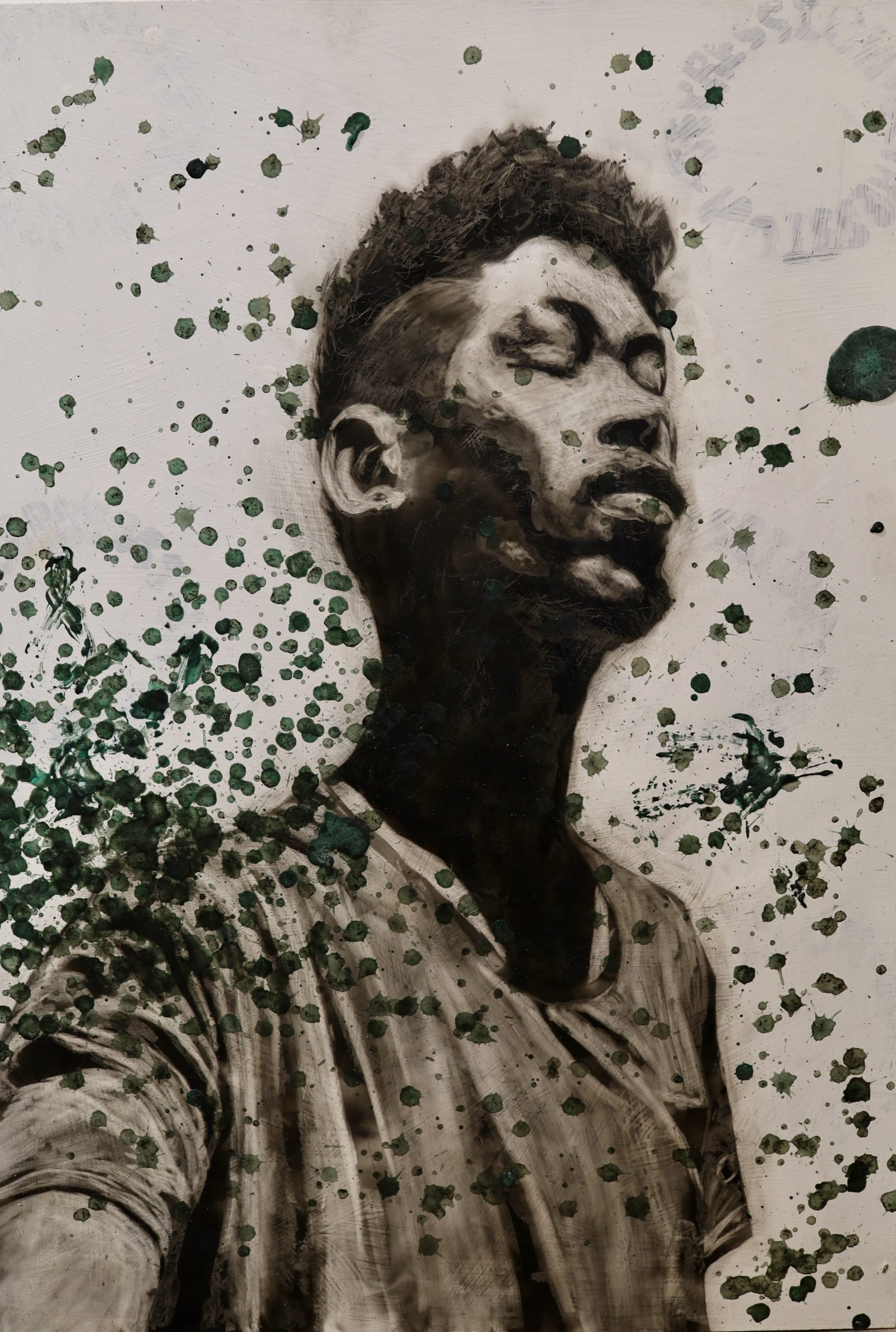

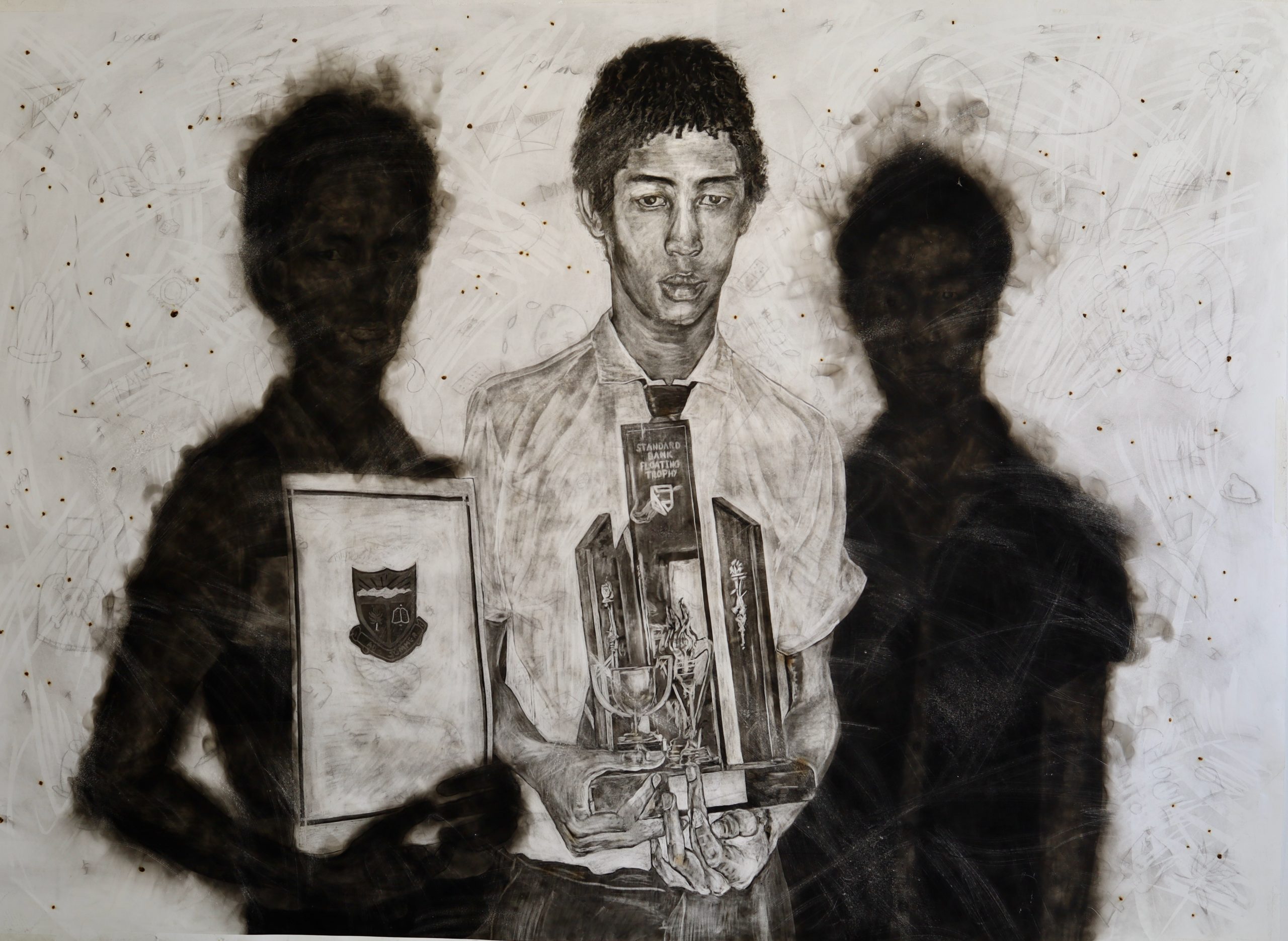

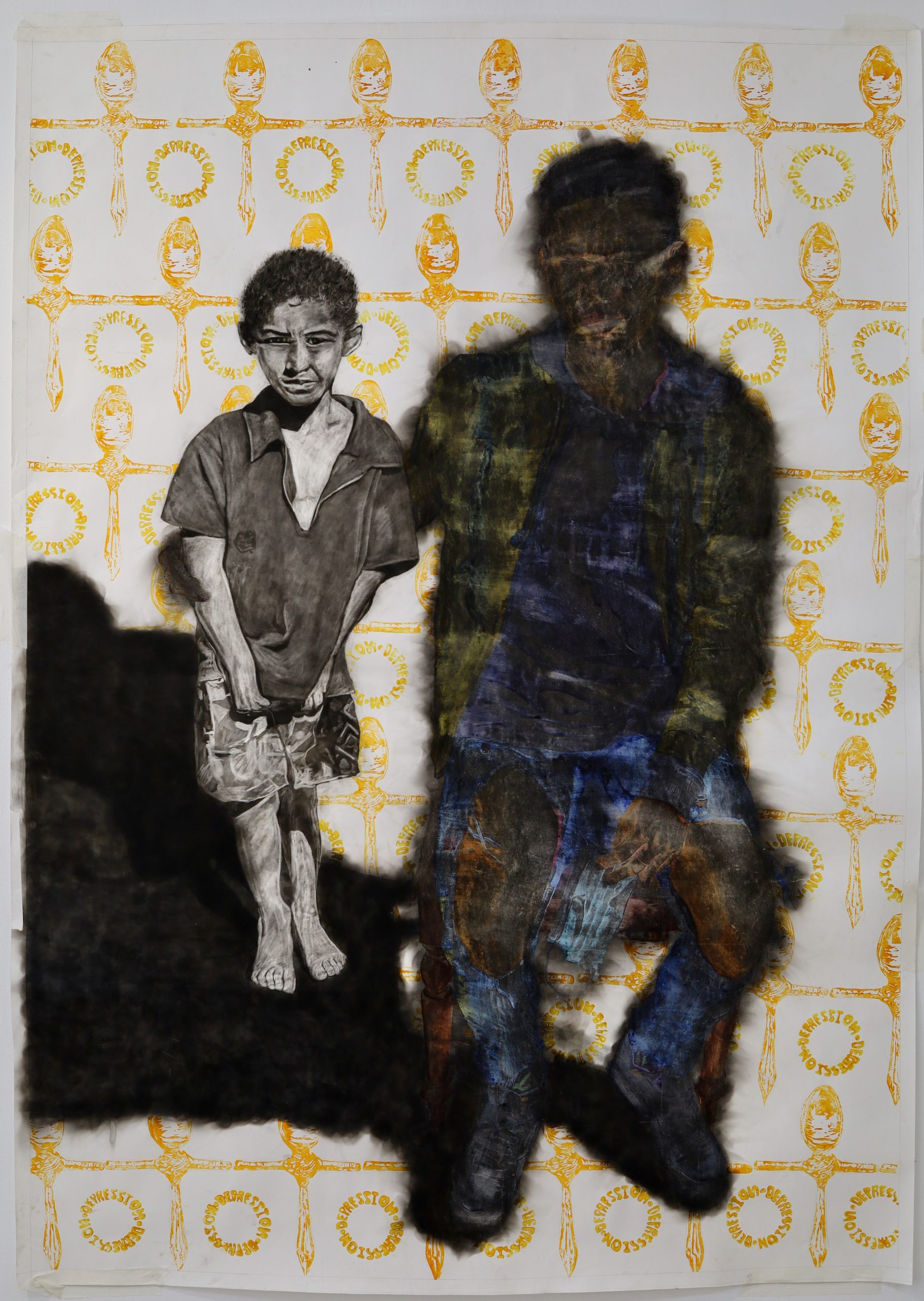

Depression shares the same attributes. My invisible prison thus becomes more apparent through the approach in my work. This idea of visibility, acknowledgment and recognition, are juxtaposed through the technique of being ‘burned’, blurred, or blacked-out in several of my works.

I felt the power of vulnerability on encountering your exhibition. Two words came to mind i.e., bravery and resilience!

Obviously, the work is an intimate and nuanced expression and portrayal of your experiences dealing with depression. Would you tell me about your decision to turn to art to help process?

BK: Ironically, my vulnerability and personal life stories are what fueled the exploration of my experiences with depression through my practice and research. It was important to be honest, and open and start a discourse surrounding mental health — as it is often seen as taboo — particularly in communities of colour. More so, the process of creating and writing about such personal life events enabled me to deal with past traumatic events, to understand myself and experiences that might trigger depression.

The process of creating the large family portraits allowed me to reminisce about the past and loved ones that I have lost. I found myself in tears, grieving not only their loss but my own death as well. After every wailing, I felt lighter. Closing yourself up to others and yourself for so long, you really do become a prisoner of your mind. The art-making process thus allowed me to free myself.

Toe ons nog kind was. 2021.

Bloed in Bloed uit #14. 2020.

Diploma Plegtigheid. 2020.

The language around mental health often fails us. We grapple with the medical jargon and the stereotypes which punctuate our everyday-speak.

At times we minimise the extent of one’s experiences. Personally, I feel your work demystifies depression, and it says it is okay to open up on mental health issues.

BK: Language plays a pivotal role in every aspect of our daily lives and is key to expressing ourselves and understanding others. Indeed, medical terms in referral to any mental illness can be extremely confusing and society’s stereotypical view on people who suffer from mental conditions aggravates that stigma. Personally, I always find it hard to explain in words when a person asks me, what depression is?

Putting your emotions into words can be extremely difficult. What aided me to express my experiences with depression and which probably influenced my focus on portraiture was when my therapist asked me to ‘paint how/what I feel’. Before I got diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder, I did not know what it was, and no matter how many times my therapist tried explaining it or I read about it, I couldn’t grasp it.

Self-introspection through my practice allowed me to fully understand what depression is and how to cope with it. The main objective in my practice is thus to influence and educate people around the issues of mental illness and advocate against the stigmatization of people suffering from mental health conditions.

What easily stood out in the work are the materials and media you employed to execute your ideas, from old family photographs to makeshift prison artefacts.

Would you tell me more about the various media you used in this body of work? You can also say a word about technique which I think depends on the materials at one’s disposal.

BK: I harness old family photographs as a departure point to investigate personal memory and more current selfies to explore my narrative of self-imprisonment. My invisible prison is visually communicated further through incorporating the visual language of prison; including tattoos, prison slang, and shivs and shanks (handmade prison weapons).

I use a variety of mediums including, charcoal, photographic transfers, paint, linocuts with a combination of burning and smoking techniques by using candle soot as a primary feature throughout my work. The prison shivs and shanks, hand-made dice from paper-mâché, glass marbles, strings, and spinning-tops combined, form provocative conversation pieces as they reflect fragments of my childhood in relation to my experiences with depression feeling like a self-constructed prison.

Die kwaaikind moet uitgebrand word. 2021.

I would like you to talk about curatorial decisions made in the two exhibition spaces if you do not mind. I obviously attended your MFA exhibition at the RAW Spot Gallery at UCKAR.

However, the images I encountered emerging out of RK Contemporary hinted on a rearrangement of the work.

BK: Of course, I don’t mind discussing it. The original body of work that was displayed at RAW Spot Gallery in Makhanda which formed part of my MFA practice evaluation, was created to specifically accommodate the space. Because the space is small and most of my work is rather large, I envisioned the installation of each piece while creating the work.

With RK Contemporary — the gallery space itself is twice the size of the RAW Spot Gallery — not only did I need to rearrange the pieces but I also created new pieces as an extension of Tronkvoë and so the re-arrangement of the pieces could speak to each other visually.

What can we look forward to soon?

BK: I am working on a new body of work that is layered in themes from Tronkvoël. We are possibly looking at a new solo show that focuses on gender identity with all the rainbow colours included through the exploration of media in my practice.

Brünn Kramer recently completed his MFA at Rhodes University, he is a professional artist dedicating his practice and research to issues concerning Identity, Depression and Prison Culture.

Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti is a PhD candidate in Art History in the NRF SARChI Chair program in Geopolitics and the Arts of Africa, University Currently Known as Rhodes

Kaskar met n bietjie luck. 2021.