“On moonlight nights the long, straight street and dirty white walls, nowhere darkened by the shadow of a tree, their peace untroubled by footsteps or a dog’s bark, glimmered in the pale recession. The silent city was no more than an assemblage of huge, inert cubes, between which only the mute effigies of great men, carapaced in bronze, with their blank stone or metal faces, conjured up a sorry semblance of what the man had been. In lifeless squares and avenues these tawdry idols lorded it under the lowering sky; stolid monsters that might have personified the rule of immobility imposed on us, or, anyhow, its final aspect, that of a defunct city in which plague, stone, and darkness had effectively silenced every voice.”

Albert Camus, The Plague

The peculiar events that are the subject of this history occurred in 20—, in countries and cities across the modern world. The general opinion was that they were misplaced there, since they deviated somewhat from the ordinary. I started rereading — but did not finish — Albert Camus’ The Plague during November/December of 2019. How opaque the memory of that time presently feels- now that there is no sense of time to feel, what with our world closing in on itself in stillness and immobility. And how retrospectively grateful I now am— there’s only so much of things falling apart; of dystopia that one can hold. The narrative of Camus’ own prolific novel published in 1947, begins with the sudden and mysterious death of rats in the Algerian city of Oran. This is then followed by “a strict quarantine of the entire population of the city imposed by unspecified military forces”. Camus’ imagined bubonic plague that grips Oran and its subsequent affects and effects on the people of the sleepy north African town is different although not removed from our current moment, in that it functions allegorically as a representation of “the struggle of the European resistance against Nazism”, according to the author in a letter he wrote to Ronald Bathes in 1955. However, our current plague in the form of COVID-19, that currently has South Africa and the world as a whole within the firm clutches of its grip is not a symbolic manifestation but a very real one. And so too are what will be both its immediate, and its long term implications for modern society, humanity, global economic systems and our ideas around justice, rights and accessibility.

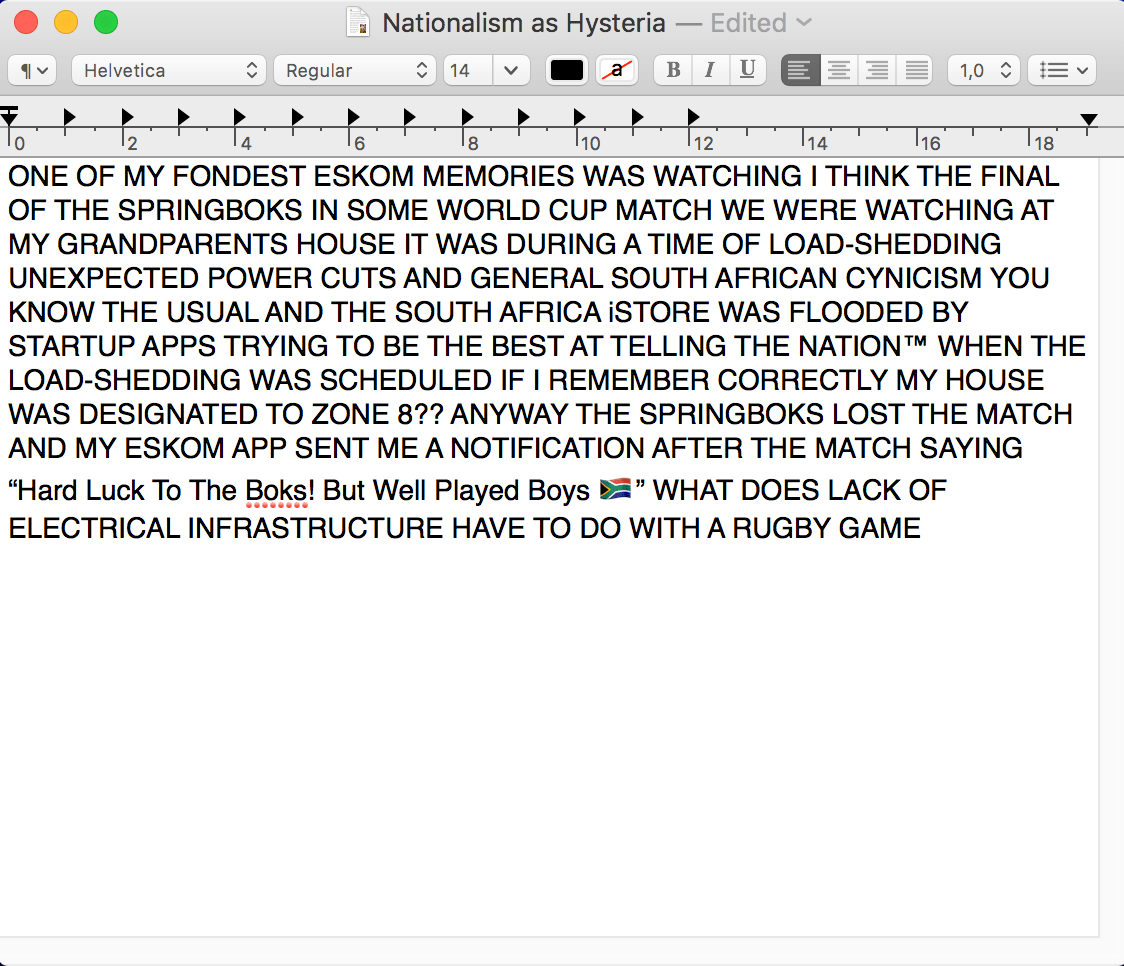

Nationalism as Hysteria questioned in a text piece

Two Mondays ago, co-president with white monopoly capital, Cyril Ramaphosa addressed the country and officially declared a 21 day national lockdown. Although this second address given by him was significantly more rooted in the historical and current socio-political, socio-economic and structural realities of the country — actually being somewhat left leaning in its proposed plan of action — along with questions about how this would work at the grass-root level of implementation, I also had a plethora of questions in relation to his omission of South Africa’s creative and artistic industries where his speech was concerned. This blatant absence of presence in addressing artistic and creative economies was also noted by a number of individuals working and creating within them, the same night of Cyril’s address to the nation author of The Girl Without a Sound, Buhle Ngaba twitted:

“the arts are blatantly omitted from every national level chat YET you consume our efforts & turn to our work at times like these. S/O to all my peers. Storytelling keeps us connected & I commend you all for staying soft & doing the work, even though they refuse to acknowledge you”.

Duae Naturae Light Box; detail (2018)

I find it hard to reconcile talking about industries and economies in a language of vulnerability, perhaps because the very language of capital reproduction makes invisible the humans behind and consumed by its systems. However, that is how many of us operating in this sector have felt at its omission from the address, not to mention disregarded and overlooked. Yes, its easy to talk about the philosophical, aesthetic, critical and even political contributions of creative industries to society, however, their contribution is also tactile and economic— in 2015 contributing R90.5 to our GDP. The Tuesday following Cyril’s address, Minster of Arts and Culture Nathi Mthethwa met with stakeholders from both the arts and sports sectors to rely the department’s position where the virus and pandemic are concerned; plans to make plans to plan- shap ke. Since then, however, there seems to be somewhat more clear and defined strategies developed by the department. As I sit here writing this, I am guided by the anxious breath of Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi’s gymnasts in Suspension (2020).

there is breathing but it is tight;

there is a moment of significance being forged in this stillness —

there is, a there but it is dependant on the here

there is…

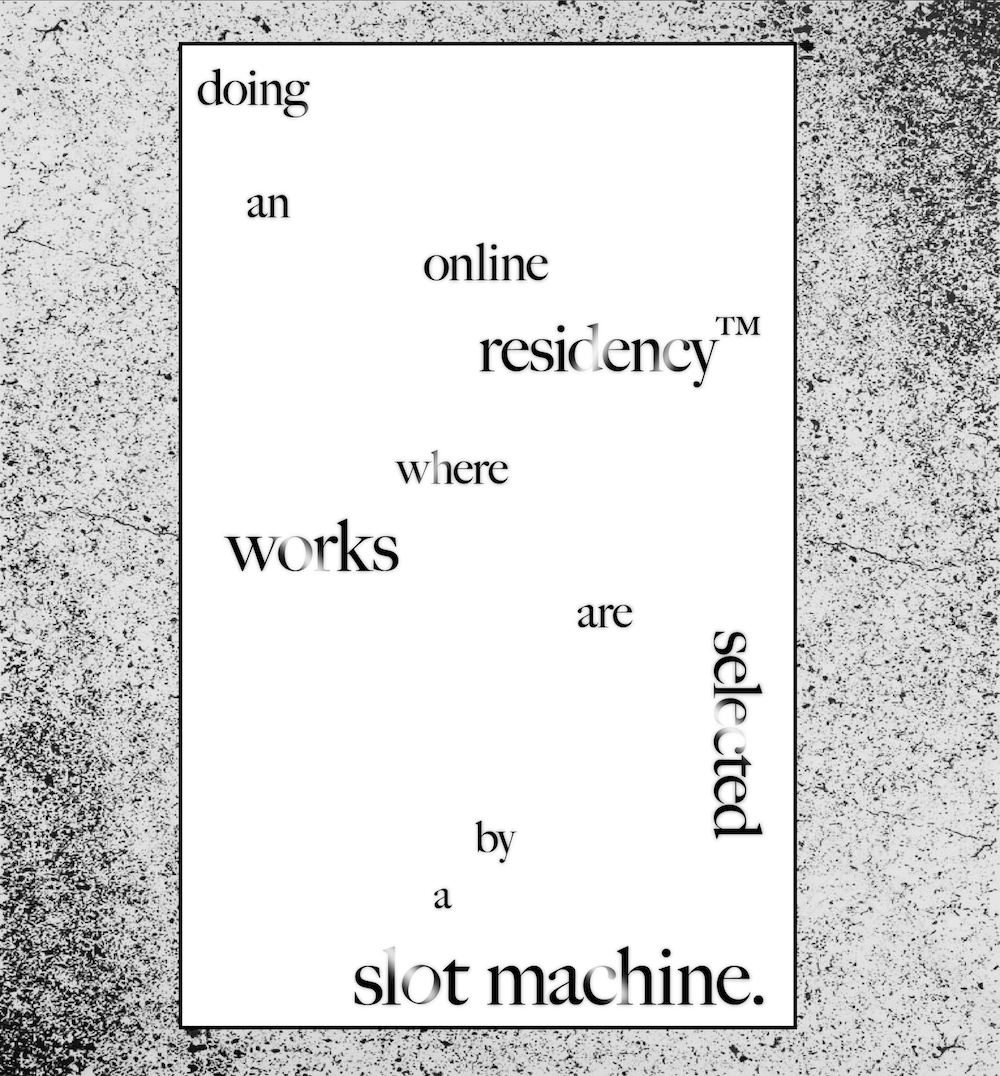

Curating as Casino explored through a poem

Much like the omnipresent narrator of The Plague, “I have no idea what’s awaiting me, or what will happen when this all ends. For the moment I know this: there are sick people and they need curing”. In attempting to think with and through this moment of suspended temporality, activity and uncertainty due to the virus, I spoke to Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho of MADEYOULOOK, and to Daniel Rautenbach who is an independent curator, designer and creative practitioner currently working at Norval Foundation. It’s hard to think through and make sense of a moment one has never arrived at or born witness to before; the mind, body and all of our feelings need time to catch up. I guess that’s what these conversations are- companions to my thoughts; a way to make sense of, however, in communion and- perhaps, this a way to feel less consumed by this abyss of suspension. The text that follows is a conversation and speculations from a place of suspension, on the current and possible future implications of COVID-19 within South Africa’s creative and artistic industries where I engage Cape Town based Rautenbach. The conversation whereby I engage Moiloa and Mokgotho of MADEYOULOOK can be found here.

Militarization as Culture expressed with a print

***

LM: Your artistic praxis and concerns are interesting in that they straddle the liminal space that fleshes itself out between the physical sphere and the digitised sphere of the internet; a tale of two worlds that aren’t really all that removed from each other. If we think about curatorial practices in the traditional sense, one could say that they are rooted in a space founded on physical sociality; this being the gallery space and its white walls. On the inverse your digitised practice although it speaks to this embodied world, can also strategically mitigate it, and by virtue of its form. How have you been engaging/thinking through/re-imagining ways of doing and working within creative industries and economies due to the COVID-19 outbreak where your own work is concerned?

Daniel Rautenbach: Well, since I’ve been working at Norval Foundation now during this lockdown I’ve been lucky enough to work from home for the last while. I’m sure you can imagine the challenge a lockdown presents to a museum. So we’ve obviously pushed more focus onto social media content and digital education. In relation to this ‘virtual and real’ dichotomy, so many institutions have been jumping on ‘virtual walkthroughs’ of the museum but in my personal opinion that doesn’t do much for me. While we have great exhibitions on show, I still think there isn’t sufficient engagement from the public with institutions on a communal level, if that makes sense? Like, beyond people visiting us. So we’ve been posting a lot more regularly with rich art-educational content and we’re putting together worksheets and other art history and basic visual communication worksheets and activities for children to do at home. But honestly in relation to my own personal practice- I haven’t been able to think about it all with what’s been going on. While my works speaks to ‘the time we’re in’ – right now if I want to say anything it has to be good and appropriate. Hence why I haven’t produced any personal/independent projects in a while (haha). But I will say, this recent focus on our virtual relationships has been fascinating to see unfold. I’ve seen some friends literally throw dance parties on Zoom or Houseparty?? As in they all dress up, maybe get some colourful lighting going, and they all listen to the same music, alone in their rooms, and dance. The isolation is definitely giving power to the virtual; and definitely making it more real. [Although] there hasn’t [been] much difference with the technology [itself]– video calls have been around for years now, but for some reason because of the enforced distancing, suddenly some digital interactions have definitely felt ‘more real’ for a lack of better words.

Virtual Installation views: Szonja Szendi

LM: I think my former question also speaks to issues of access and such, which already plague our creative and artistic sectors and industries. Especially given our countries socio-political and economic history. Do you think that this moment could resonate in ways that force institutions, galleries, collectives etc, who are creating, thinking, playing and working within the creative industries to start thinking about these issues- and ways to address them, in less abstract and intellectualised ways and perhaps in more practical ones?

Daniel Rautenbach: Well first and foremost, I’ve been privileged enough to still have a stable job during this time. But I understand and can only imagine how stressful it must be for more independent cultural workers. I WANT to say that this time – particularly the lockdown – has hopefully opened people up to the creative industry. Hopefully people are more appreciative since we have ‘the arts’ to keep ourselves entertained, or even sane, during lockdown, and that maybe it is one of the few things able to keep peoples’ spirits up. But it’s difficult for me to keep this attitude with the stress other workers are experiencing in this country. [Although they are] not creative practitioners at all, watching grocers, healthcare workers, pharmacists and delivery drivers vulnerably continue ‘business as usual’ while we are able to stay safe in our homes has made me feel somewhat cynical of a lot of the creative industry. Not that it isn’t necessary of course, but this virus has in multiple ways really illuminated the ills of class within society. I wouldn’t be surprised if use of the word ‘billionaire’ has spiked dramatically this last year. I just mean when we’re talking about practical things – I wish more people acknowledged and paid these everyday labourers [better]. I think in some ways the situation has showed us that the money is there and it can be circulated, but also that so many low-income positions deserve more. That being said, I will reiterate that culture will always exist and is an intrinsic feature of the human condition. If we don’t nurture it, we will become socially numb and regressive. If anything whilst we’re being isolated, it’s culture that keeps us going – even beyond the ‘be grateful for Netflix’ dialogue, but just understanding the things that exist outside of money and health, that fill the gaps and are unique to us keeping our heads up.

Regarding institutions taking more accessible approaches, while yes – focusing on the digital can make content more accessible – but physical and monetary restraints will always be the biggest drawback of the art world. I even saw this performance artist respond to the growing rhetoric of ‘make art online with all our free time!!’ – and basically said “why would I do something online for fewer people for free?” which is a great question. People often act entitled to the arts as if it’s our civic duty to perform, entertain, distract as if we’re not also living in this crippling economy. I think hopefully after this isolation, this time we’ve spent online will help a form of mobilising or at least just coming together ‘IRL’ just to make things happen. We need more independent cultural projects outside of institutions and I suppose the internet is still where it will start.

Own Your Content (2018)

LM: Black feminist, scholars and writers have referenced and spoken about the margin/states of deficit as holding a certain transgressive power and as also being spaces of radical openness and possibility. Moving on now to the moment after this suspension; once the bus has arrived, the virus has been contained and our moments of silence have been observed- what radical possibilities do you think could potentially come out of it? [again, speculation]

Daniel Rautenbach: I saw a friend post a quote from Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower from 1993, “but it took a plague to make some of the people realize that things could change”. The conversation covers this idea of transgression – “Our adults haven’t been wiped out by a plague so they’re still anchored in the past, waiting for the good old days to come back”. Maybe it’s dystopian opportunism- but I do feel like this pandemic will have a larger effect than most disasters we’ve experienced. And this has definitely got me thinking about different ways in which the global power dynamics are being challenged and are shifting. It stirs something inside me when these characters in our world believe the virus is a [sort of] fiction – as if they themselves are playing a game of Plague Inc. but with the ‘it doesn’t happen to me’ mentality you know?. Boris Johnson was parading the fact that he was visiting COVID-19 patients and proudly shaking their hands, and has now been tested positive himself. Brazil’s Bolsonaro also tested positive, and much like Trump has been downplaying the pandemic to be some sort of ‘leftist’ ploy.

We have various potential outcomes of this situation. For some people it is a game. Several American senators heard rumours of an accelerating virus and immediately sold off millions worth of stocks. Jeff Bezos did the same. We’ll always have disaster capitalism but I must admit, at least in South Africa, the opportunism hasn’t felt as sinister as we’ve seen in the past. The shared experience, exaggerated through social media and online realms, is definitely something to note. I can’t bring myself to be the one to refer to ‘nation building’ but I think there is value in people of all backgrounds having to share certain experiences. Either that, or now we know [that] some meetings can just be emails.