Woodcraft holds a strong presence in many communities and cultures around the world. For the people of Zafimaniry, which is a community in the southeast highlands of Madagascar, woodwork is not only a central practice among the people but is deeply embedded in their culture, livelihoods and belief systems.

Quentin Clemence and Alice Weil founded Studio ICAI (Interdisciplinary and Caring Architecture – For the Inhabitants), where they work between disciplines to research and create architecture in accordance with the communities they work in. Their project, From ‘House-being’ To ‘Having A House’, explores the woodwork practices of the Zafimaniry community.

Woodcraft traditions became a central part of Zafimaniry culture in the 18th century when the nomadic group moved to the densely wooded area as deforestation ravaged the environment. The knowledge and skill of wood-crafting have been passed down through each subsequent generation, building an intimate relationship with woodwork that forms a central part of their community. They use twenty endemic tree species in their craft, creating both decorative and functional structures without nails, hinges or metallic tools.

However, deforestation continues to be a threat to the natural forest reserves in this area and to the communities whose livelihoods depend on it. Zafimaniry woodwork was listed as one of UNESCO‘s sites of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008, as part of the UN’s commitment to preserving the knowledge and heritage of the Zafimaniry community.

As part of her Master’s research in social anthropology, Weil studied the role of woodcraft in Zafimaniry culture. Clemence is a French-Swiss architect working towards specialising as a heritage architect at the Paris School Of Architecture.

In combining their research fields and practices, Clemence and Weil examined the impact of globalisation on the architecture of Madagascar, in partnership with London-based environmental consultancy firm AtmosLab. Studio ICAI’s project used research on local knowledge and cultural practices of architecture, culminating in a multi-media exhibition, showcasing video recordings, soundscapes and Zafimaniry artworks.

What drew you to the Zafimaniry woodcraft practices?

We had been working in Madagascar for several years, conducting research before this specific project. I was able to learn about local architecture as well as the globalisation of architecture and construction techniques in this geographical isolation (the villages where we worked have no roads, water or electricity).

We have acquired a certain amount of knowledge about the Zafimaniry country, which will now form the basis for further research into the architectural and climatic challenges of this region of Madagascar. Part of our new research is to establish links between local knowledge and customs related to architecture, their transformations and environmental data.

Why do you approach architecture from an interdisciplinary perspective?

If our experiences in the field have taught us one thing, it is that there are as many definitions of architecture as there are people willing to give them. If we were to take the gamble of stating one here, we would say (without taking too many risks) that architecture is the spatial mediator between us and the world, and vice versa; any transitional space between us and the world can systematically be integrated into the field of architecture.

We, therefore, rely on the greatest possible openness to other approaches, other methodologies, and other theoretical bases than those specific to our profession, in order to understand and produce architecture – whatever it may be – with a concern for accuracy and measure.

This attitude never ceases to bring us closer to and further away from our field, in projects that sometimes send us where no one expects us, and from which we draw with interest all the data to establish the best relationships with others (collective or personal), thanks to all the technical and technological, aesthetic and artistic, historical or anthropological acquisitions that we accumulate.

What does your practice entail?

Our practice is largely influenced by the discoveries we make on-site. By looking at specific situations on the other side of the world, we approach the questions of globalisation, know-how, and climatic and social issues of architecture in a different way. We attach particular importance to local materials, the mastery of adapted construction techniques, ecological and comfort requirements and climatic coherence in the design and architectural analysis.

In addition to their project, From House-being to Having a House, we worked with local designers and architects for Tana Design Week, an exhibition showcasing and supporting the work of Madagascan designers.

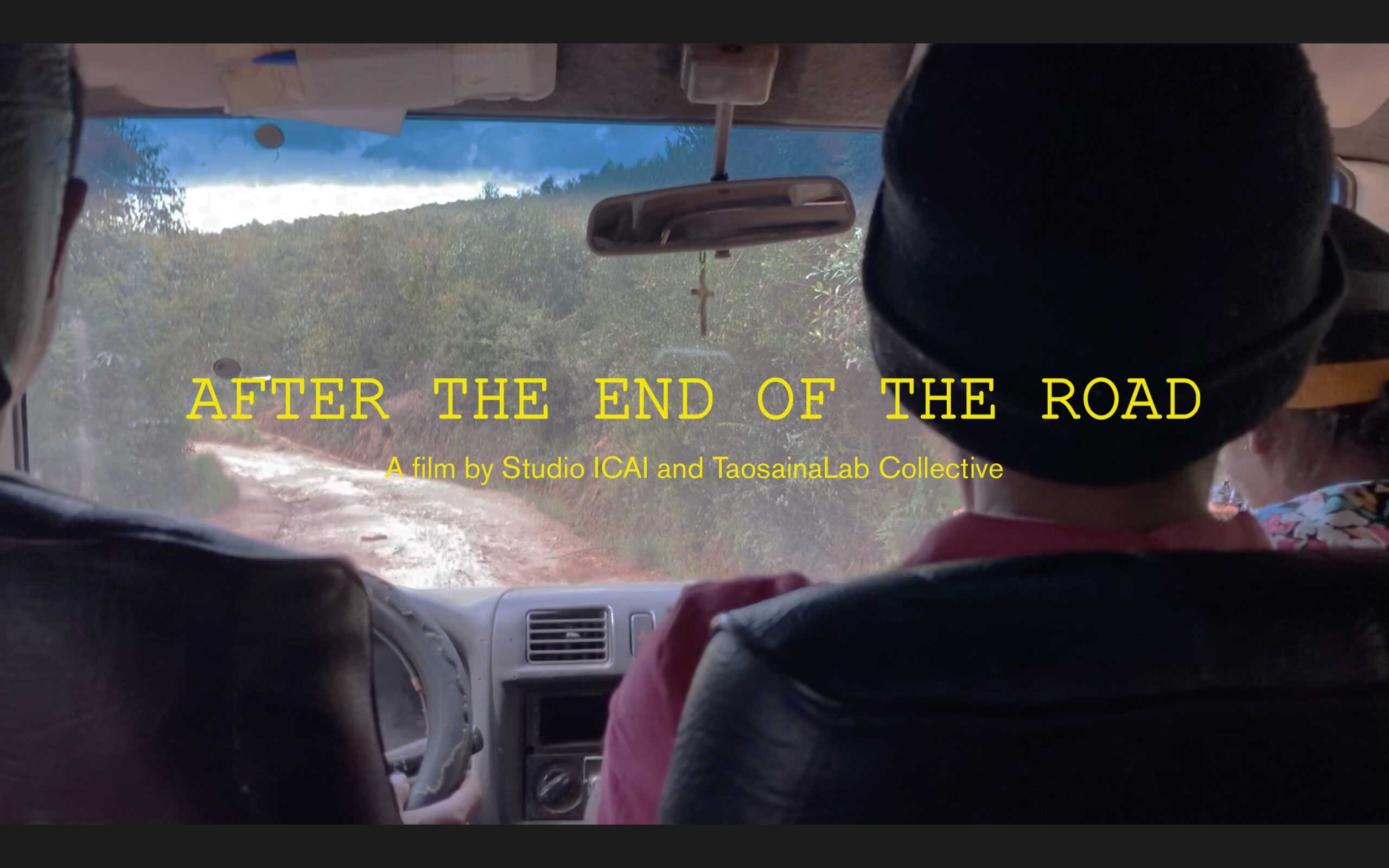

At this exhibition, Studio ICAI collaborated with Malagasy collective TaosainaLab and presented a short film, After The End Of The Road, as a proposal for rebuilding a primary school in the rural area of Mahitsy. The school, which is situated in an isolated area, is in great disrepair.

Can you explain more about this project?

The discovery of local building techniques gave us the desire to design architecture in accordance with the community. We were able to put this into practice on a small scale, in an installation that we presented for the Tana Design Week 2023 exhibition (After the End of the Road).

We are also working, on a larger scale, on a project for a primary school in the commune of Mahitsy (40 kilometres north of Antananarivo). In addition, our research in Madagascar has also led us to develop a feature-length creative documentary film about a young man from the Zafimaniry country who is building a “modern” house in the middle of his native village.

This story is produced in the context of an editorial residency supported by Pro Helvetia Johannesburg, the Swiss Arts Council.