“I think perfection is ugly. Somewhere in the things humans make, I want to see scars, failure, disorder, distortion.” ― Yohji Yamamoto

Some would say, that fashion is most notably recognised for its exaggerated silhouettes, patterns and hues, at least that most mainstream fashion is. Some would say, that fashion elicits dramatic sentiments and the eternal human pursuit of perfection; a paradoxical notion largely suspended in non-existence. It is in this vein of myth and fantasy that so much of fashion arises from – the frontiers of creativity dreamed into reality in magazine spreads and on screens. We seek the embodiment of the divine and incantations of other realms with stitch and drape; calling our cosmic counterparts to dance with us along the runways. What happens, though, when we omit the grandeur? When we expose the seams, slash the hems so that they are ragged and remain unfinished – distort the shape and form of the garments? Well, we stumble upon a realm of fashion entirely unique and provoking; anti-fashion. We witness the dissemination of traditional construction principles, and the employment of rebellious, self-governing rules; evoking a new frontier in fashion where designers are upcycling, rehashing and reshaping the paradigms of what it means to be “stylish” – or dare I say, “fashionable”.

in text photography sourced from Pinterest

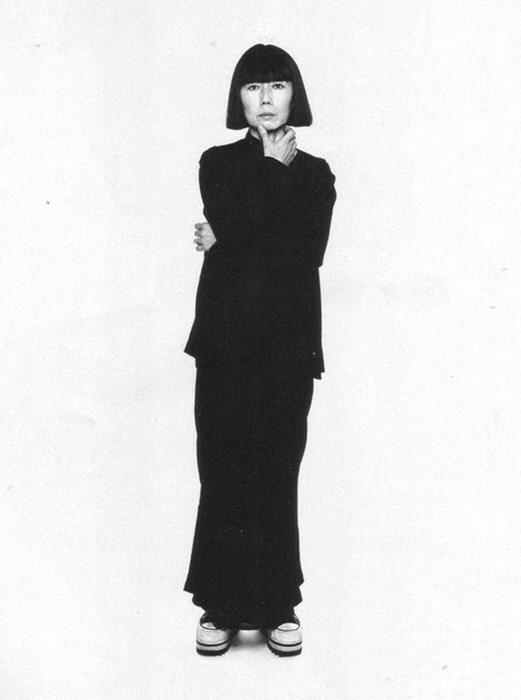

Yohji Yamomoto and Rei Kawakubo; the poster designers for avant-garde fashion originating in Japan, completely tore a rip into the fabric of Parisian aestheticism; utilising disproportion, asymmetrical cuts and with monochromatic tones that served as a social and political statement against the grotesquely excessive aestheticism of the 1980s. Yamomoto pioneered grunge-ish detailing by rejecting high heels, glamour and overtly perceivable “sexiness” in womxnswear. Kawakubo, in one of her many deeply considered shows, sent models down the runway in dresses with huge, misplaced padding, this serving as a critique on the cultural exaggeration and pathological obsession with the femme form. It was this dive into the deeper psychological nuances of expression and identity through the medium of fashion that sparked my own realisation as a teenager, that fashion could be so much more than the vacuous, ego-centric monster it had become throughout the modern era. I had sought more from fashion through my painstaking love for it; quickly learning that there is inherent meaning in what we wear. Clothing is our second skin, our second and most immediate home next to our bodies. Thus why would it not be a statement of who we are, and what we want to communicate about our values, principles and instincts?

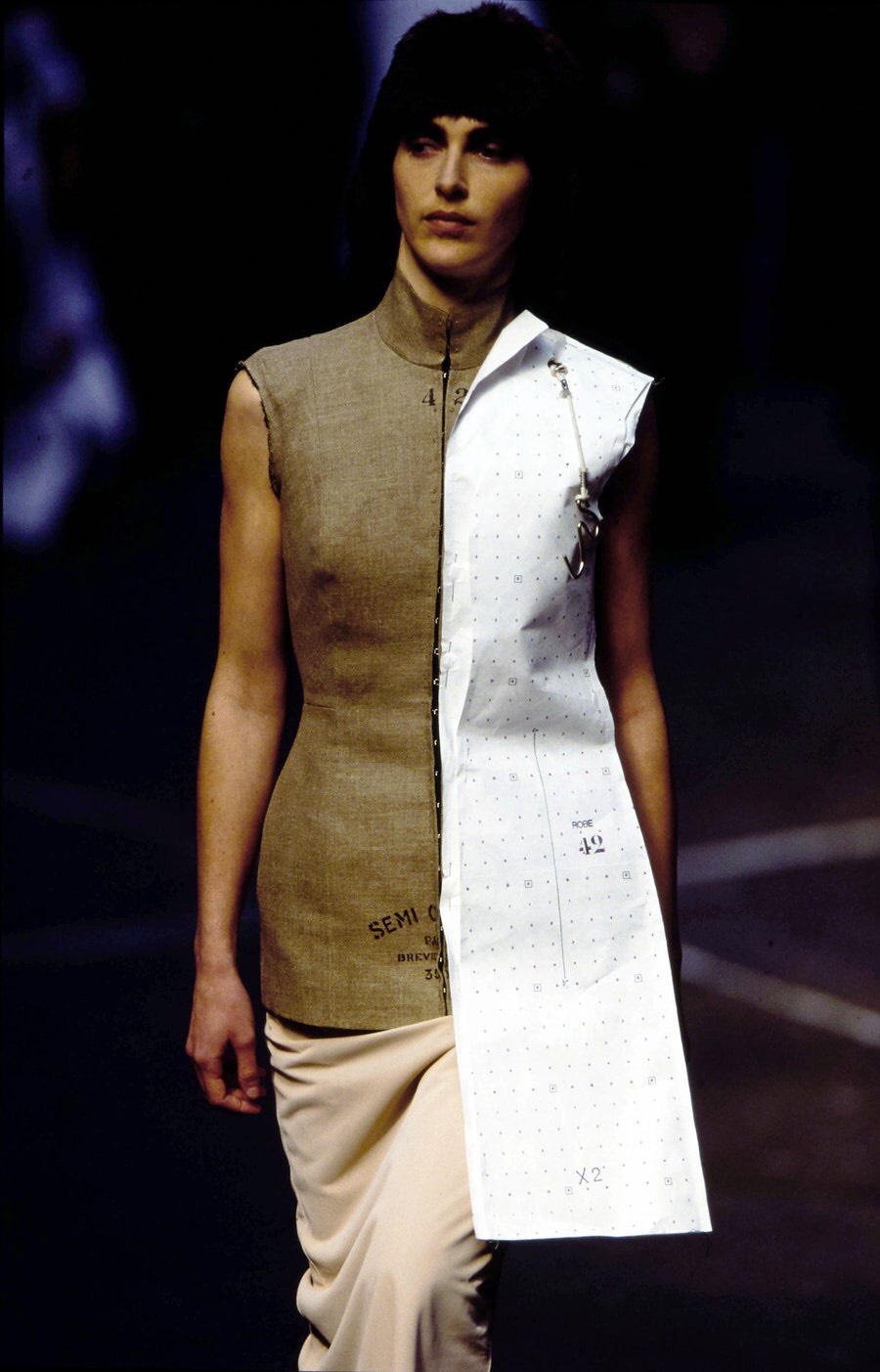

Another notable titan of anti-fashion is none other than Martin Margiela; one of the original “Antwerp 6” who burst on the European fashion scene in the 1980s. He was head-hunted by Jean Paul Gaultier, who later pushed him to start his own label; “I already knew he was good, but I didn’t realise (sic) to what extent,” Gaultier later stated about the designer. Margiela would go on to disrupt fashion presentation in a major way; abandoning cold, clinical show rooms and runways, choosing rather to opt for parks and public spaces and therefore ushering in the idea and space of interactive shows with the audiences alike. In 1992, Martin Margiela put on a show at the Salvation Army, showing garments made from recycled fabrics, contributing significantly towards fortifying the designer at the helm of subsequent upcycling aesthetics that are now evermore popular; from Ottolinger, to Marc Le Hiban and Soup Archive. It was a noted statement; a stab and parody at the “luxurious” and intensely excessive nature of fashion to discard materials and lay waste to the earth.

Fashion is an intimately and immutable archive of the cultural and historical nature of our evolution; of this, I am sure. In a digital and corrupted society, fashion’s latest iteration is fast, preying on our most hedonistic desires of materialism. Anti-fashion is a movement of disruption, dedicated to altering our notions of silhouette, form and production before — and perhaps beyond — the rise of “sustainability” in fashion through the idea that our consumptive habits and industrial-cultural-complex is wreaking havoc on our psyches and consciousness. I am particularly enamoured with designers who utilise their voice and platform for disturbing, diabolical causes – in as much as society’s expectations are concerned. In anti-fashion, we choose to dress ourselves. We choose not to allow conglomerates, board rooms and economic paradigms to dictate our accessibility to expressing our identity and the modes through which we do so. In anti-fashion, we find a rebellious purpose with a cause and with the cultivation of a considered, well designed and avant-garde existence. Beyond binary and singular entrapments, and towards a celebration of the understated magnificence of what it means to simply be alive.

Design and fashion attest to some of our greatest artistic endeavours as a species, and we are currently facing the emergence of a rapid decline in the ecological health of the planet. To marry these two realities as a force of expanding our collective consciousness through solution-based models of consumerism, we can stand to bring about the most exciting time in technological mastery which becomes even more exciting when considered in the vein of anti-fashion and disruption. With movements such as these drawing on multiple models of criticality where society, socio-economic inequality and capitalism are concerned; perhaps we can use the creative medium of fashion, one that is inclusive in honouring our biological form in all their variations and nuances, along with the planetary temple that provides us with a home & resources thus ultimately recognising Earth as a celestial being that nurtures us by the sheer devotion of natural order. It is, I believe, our responsibility to reciprocate this homeostatic relationship – and to challenge anything that brings excessive imbalance to it. As Issey Miyaki once said, “I have always been interested in conducting research that yielded new methods by which to make cloth, and in developing new materials that combine craftsmanship and new technology. But the most important thing for me is to show that, ultimately, technology is not the most important tool; it is our brains, our thoughts, our hands, our bodies, which express the most essential things.”