The artist talks experimental sounds, healing, Johannesburg displacement and trauma on Grindr.

“To be honest, I can’t even tell you what I was healing from”

Desire laughs over the phone with me. I’m on a midday call with Desire who is in their hometown situated in KZN as he graciously accepts the interruption. With this new, self-titled album, he was working through feelings of loss and displacement. At the same time, running on the high of being one half of, arguably, the country’s most boundary-pushing musical act. “I guess I was just healing from life”, they continue. He tells me about watching Barry Jenkin’s Moonlight, the Oscar-winning portrait of Black gay masculinity, saying that the film made them confront the possibility of no happy endings. Pondering his own process, Desire tells me “50% of it is realizing that my life [and living with] my identity is something that I might actually have to heal from. The other 50% is things that I still don’t necessarily understand”.

From start to finish, Desire sounds chaotic. At the opening track, a blend of disharmonious sounds with no lyrics give way to jarring silence. On “Zibuyile Izimakade”, heavy synth and discordant everything-else, make you feel trapped in some sort of dark round-up roller coaster, spinning frenetically before Desire’s voice swoops in like the lead tenor in a church choir. Moments like this are contrasted with the softer songs that have a sadness the beat doesn’t conceal. The lead single “You Think I’m Horny”, is 80s-electro meets the Weeknd-esque sad-boy penmanship and FKA Twigs’ baroque, avant-garde flavour. The lyrics are written more like prose than a pop-song, as Desire looks for intimacy and comfort in someone who he doesn’t want to fuck, they just wants to be with. Laughing, Desire says “I hope people don’t have any expectations. I hope they aren’t expecting a dance album”.

Photograph by Jamal Nxedlana

Desire sound’s like an alternate universe to the last five or so years of FAKA. With Fela Gucci as the other half of the equation, FAKA has seen their ancestral gospel gqom, soundtrack Versace Menswear, Telfar and stages across Europe. In many ways, FAKA has been the 2010’s answer to New York’s 1980s ballroom scene. Desire and Fela have become a kind of nexus around which Johannesburg and Cape Town’s upcoming queer DJs, influencers, models etc have circled. In their work (see the Queenie music video) and on their Instagram’s, there are a barrage of recognisable faces that can be transplanted from Kitchener’s to The Waiting Room. However, on this new project Desire stands on his own, unsupported sonically or visually by this popular chosen family network. When we talk about the decision to go solo, they speak about it as natural progression. Where FAKA is something that has an obvious larger project in shifting culture, this album felt like something he had to do to enrich both himself and the collaborative project of the group.

“I don’t know how to say this without sounding woo-woo but-”. We both laugh. “I felt like I had to answer this call, a call to create this body of work.”

In an interview from 2017 with Beth Vale, Desire talked about the concept of ‘nivea-ness’, putting on masks to protect others from the burden of ourselves. He described this feeling in that interview as “carrying a lot but putting your best foot forward, kind of vibe. The fact that you are ‘Nivea all-over’ like Vaseline”. On this new album, Desire seems to have replaced staple-brand body lotion for ashier skin. A song like “The Void”, sounds like a literal entering into darkness. The gristling, scraping and growling of some kind of creature layered over minimal keys, sounds like a system glitch. The ferality of that song runs up hard against “Uncle Kenny”, a friend-love song named for artist Nkhensani Mkhari, where Desire apologizes for not being there for those closest to him in the ways that he wishes he could be.

In many ways, not in the least sonically, Desire is an album that is both global and deeply rooted in Johannesburg. I point out to them that, unlike music coming out of FAKA, most of this project is in English. When I ask if there was any reason for the linguistic shift, and he ponders… “I don’t know, maybe there was something about English that is easier to express that pain in”. We get to chatting about his early move from KZN to Joburg. Throughout the project, the idea of being lost in the concrete metropolis comes up again and again. It has been Desire’s second city since high school, where they attended the National School of the Arts, a hub for burgeoning talent and a breeding ground for Braam-bound teenagers. When I ask Desire what sticks out to him from that time, they mention the classism they experienced, coming into that environment. “In so many ways, at that time, I felt like people were using my identity [as a way to] not hear me. Everything I said would be overlooked because of the way that I talked or the clothes that I had on…to the point where I was assimilating just to be heard.” Even outside of youthful growing pains, the feeling of being displaced and swept up in the belly of the beast is palpable, both for people who grew up in the city and its recent transplants.

Photograph by Sir Zanele Muholi

What is most inescapable on the tape is Desire grappling with love. I ask him about something he tweeted earlier in the week, about the shame that comes with being on dating apps as someone who is visible in the public sphere, especially when the idea of finding intimacy is still mediated through a straight, vanilla lens. “I use Grindr like Whatsapp or Instagram” he says. “And a lot of what I see there is men…traumatised by manhood. I think there’s a sense of trauma from rejection that shows up and manifests on Grindr.” On “Ntokozo”, a song written about a lover sourced from that app who then ghosted him, Desire plays around with trauma and rejection both internal and externally. As much as that song seems to be about the pain of romance born online, it’s also about his relationship with himself. Thinking about it, they say “maybe it’s about me not making the right choices, not standing by myself always.”

As we round out the conversation, I come to ask him about the last track, “Studies in Black Trauma” (which…you just have to hear it). I call it chaos. He laughs. He describes this moment as him coming to terms with the ‘destructive’ parts of himself and then being exorcised in the middle. Towards the end of that song, there’s a sense of heartbreak but also clarity. Desire sighs, “it’s the dynamics of the trauma of being black”. The spiritual tub of Nivea cream lays on the bathroom sink, only minimally used.

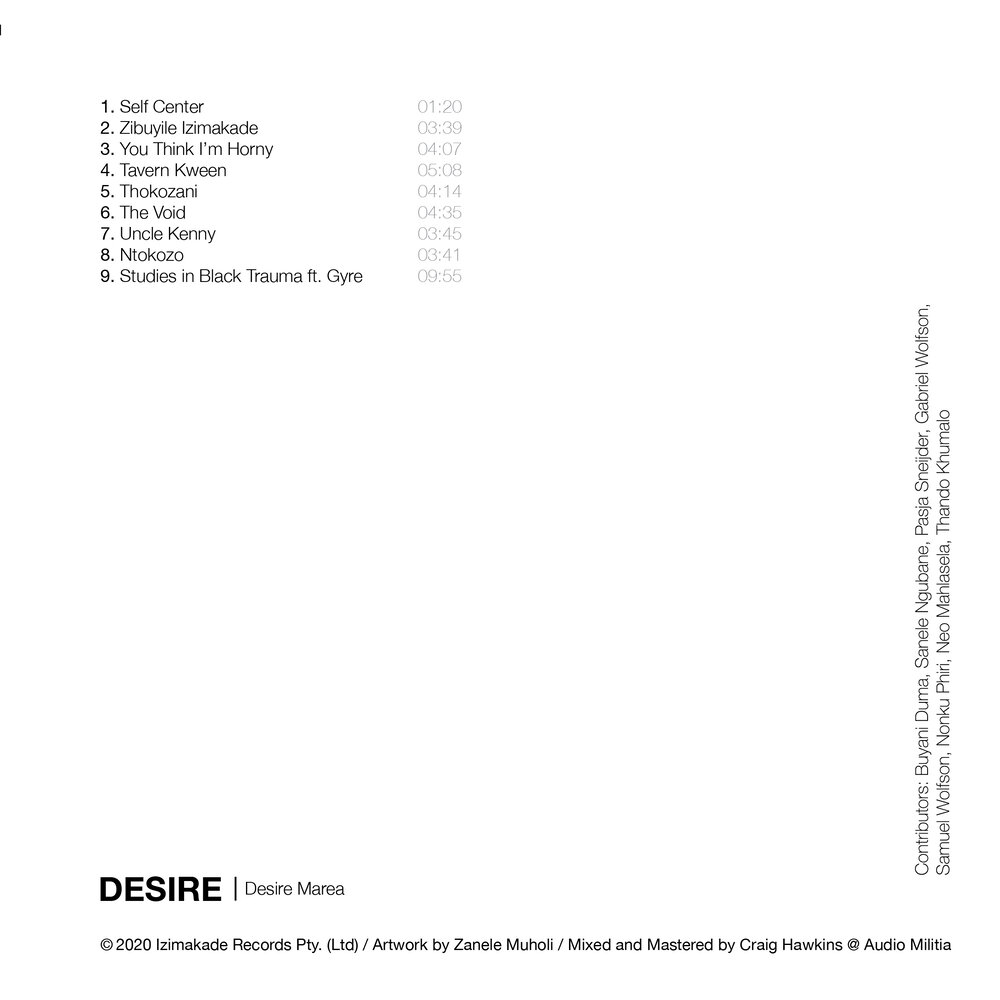

The album is now fully available for download on all major music streaming sites and listen to it below.

https://soundcloud.com/bobmarea/sets/desire