As much breath, depth and comfort I tend to find in the spaces of (re)memory and remembering, they are also thickly populated with disappointment and leaking holes and cracks that seem to filter out—more often than not—the work and presence of Black femmes where H/history and artistic cultural production is concerned. We often hear people talk about how so and so person or artist is “underrated” from Busta Rhymes to Ms Janet Jackson. However, is it truly sincere critique to position this type of erasure and silencing within the passive middle ground space of being “underrated”, rather than framing it within socio-historical strategies of whiteness that deliberately seek to make invisible, invalidate or co-opt the work and artistic legacies of Black femmes? As Barbara Smith writes in her 1977 essay, “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism,”

Black women’s existence, experience, and culture and the brutally complex systems of oppression which shape these are in the ‘real world’ of white and/or male consciousness beneath consideration, invisible, unknown … It seems overwhelming to break such a massive silence.

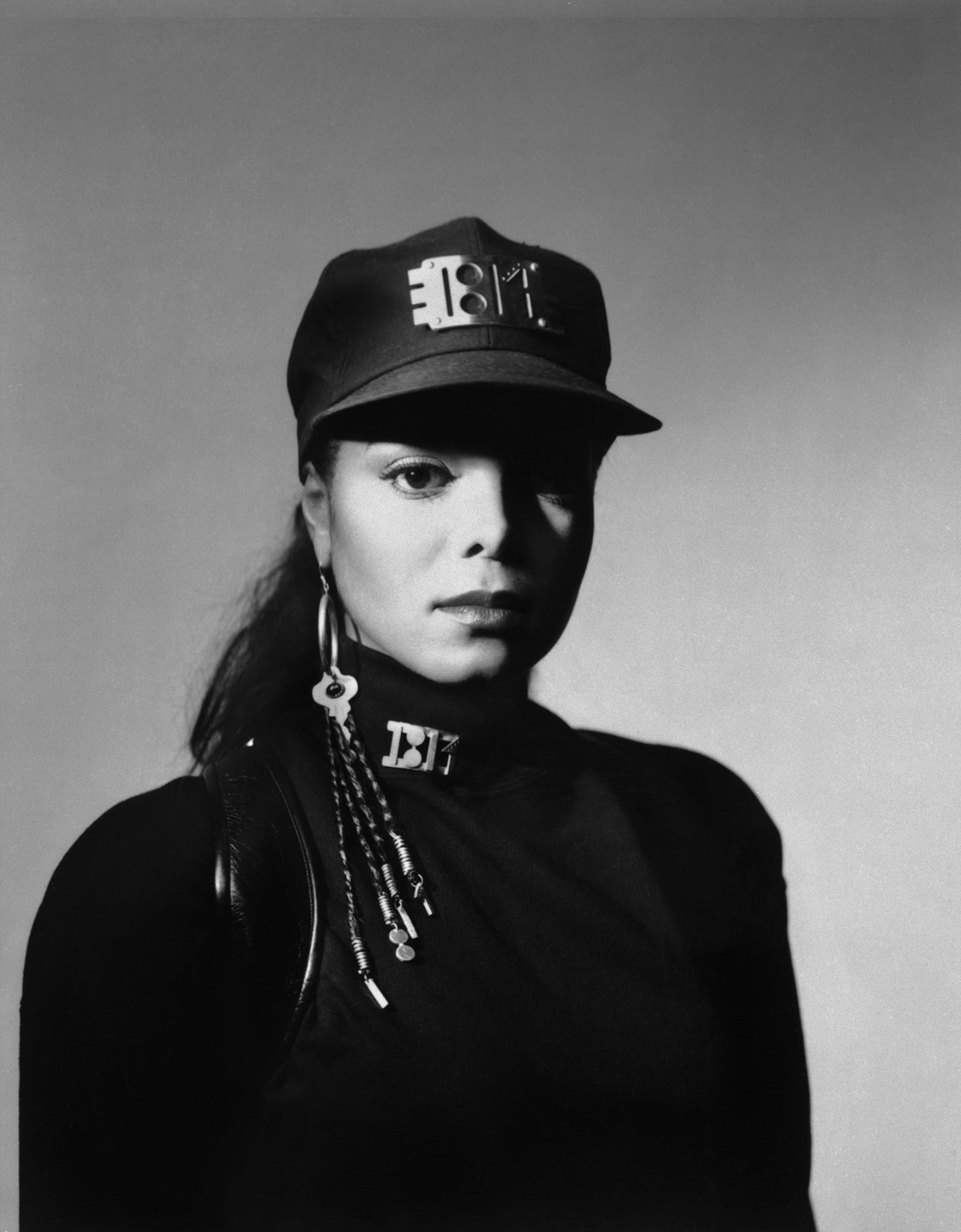

Long before Beyoncé was flashing the word ‘feminist’ in the background while performing on stage and sampling the words and thoughts of TERF feminists such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on her songs—Janet was exploring how navigating the world as a Black woman is never not political. As expressed by Dr Kirsty Fairclough from the School of Arts and Media at the University of Salford:

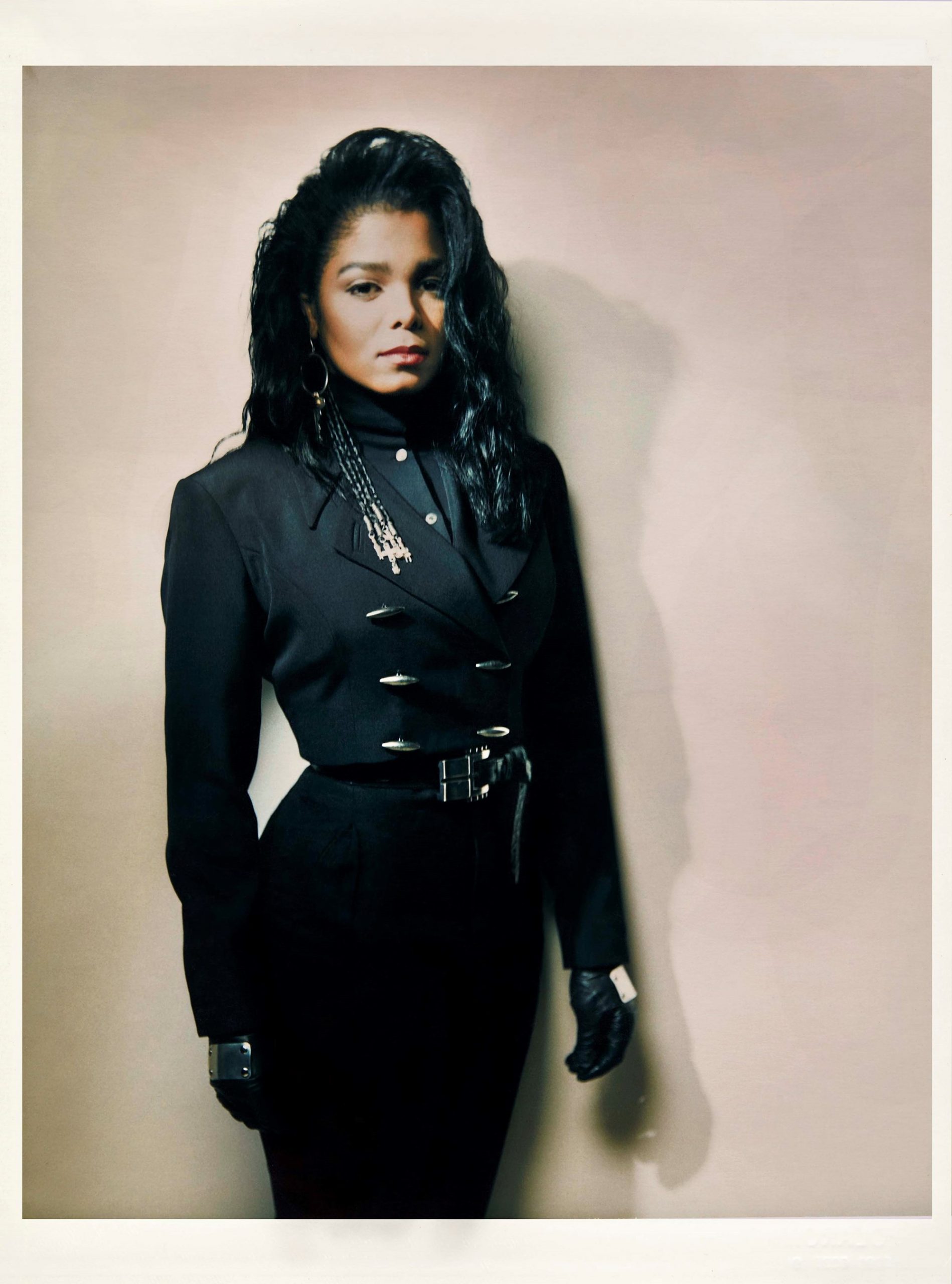

Her music and image melded to explicitly address racism and sexism with songs about trying to flourish as a person in an environment ruled by both. In a 1987 interview following the release of ‘Control’, Jackson responded to a question about being a feminist by saying, ‘If it’s someone, a woman, who’s taking control of her life as well as her career, then I say that I am a feminist.

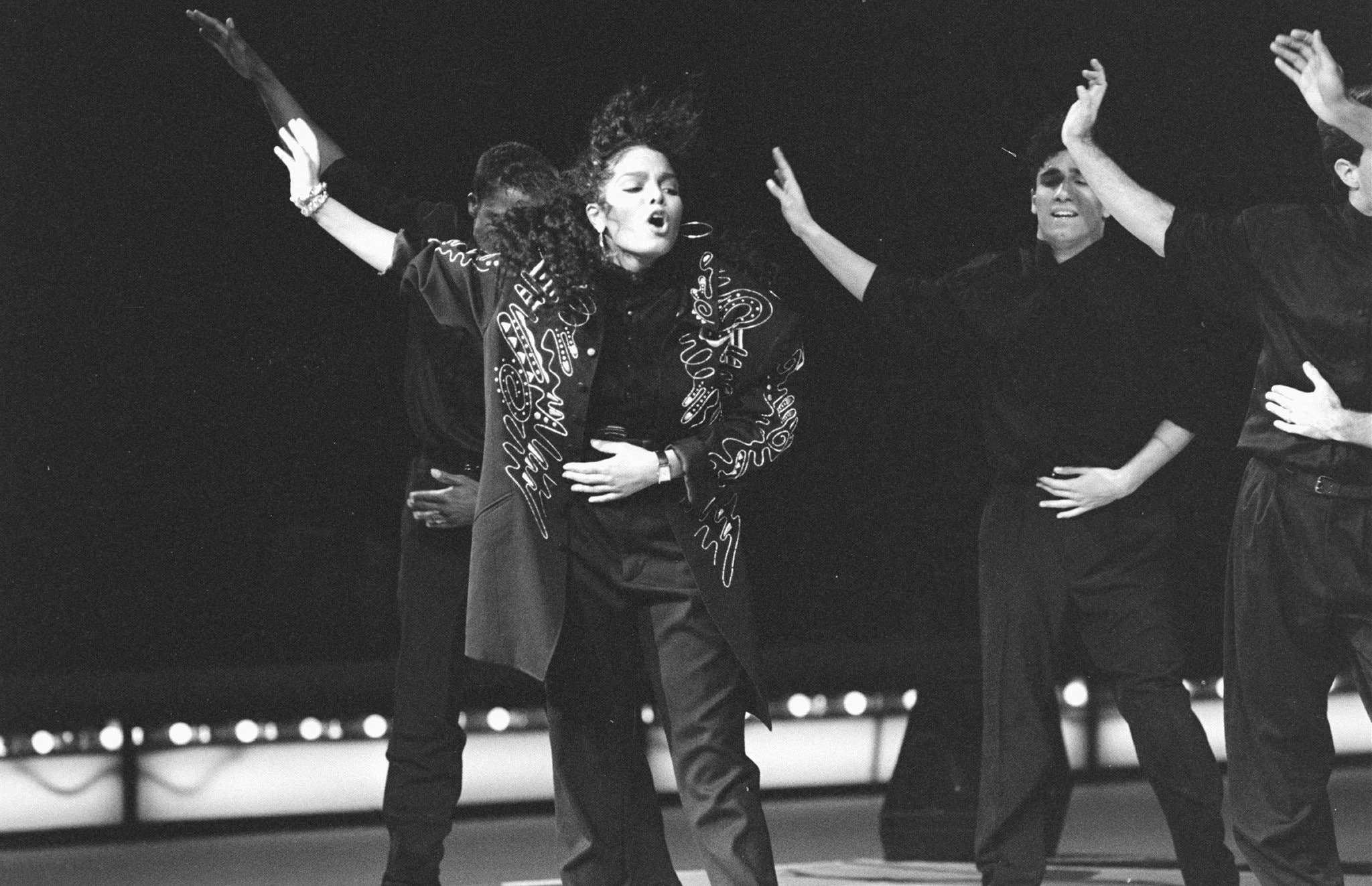

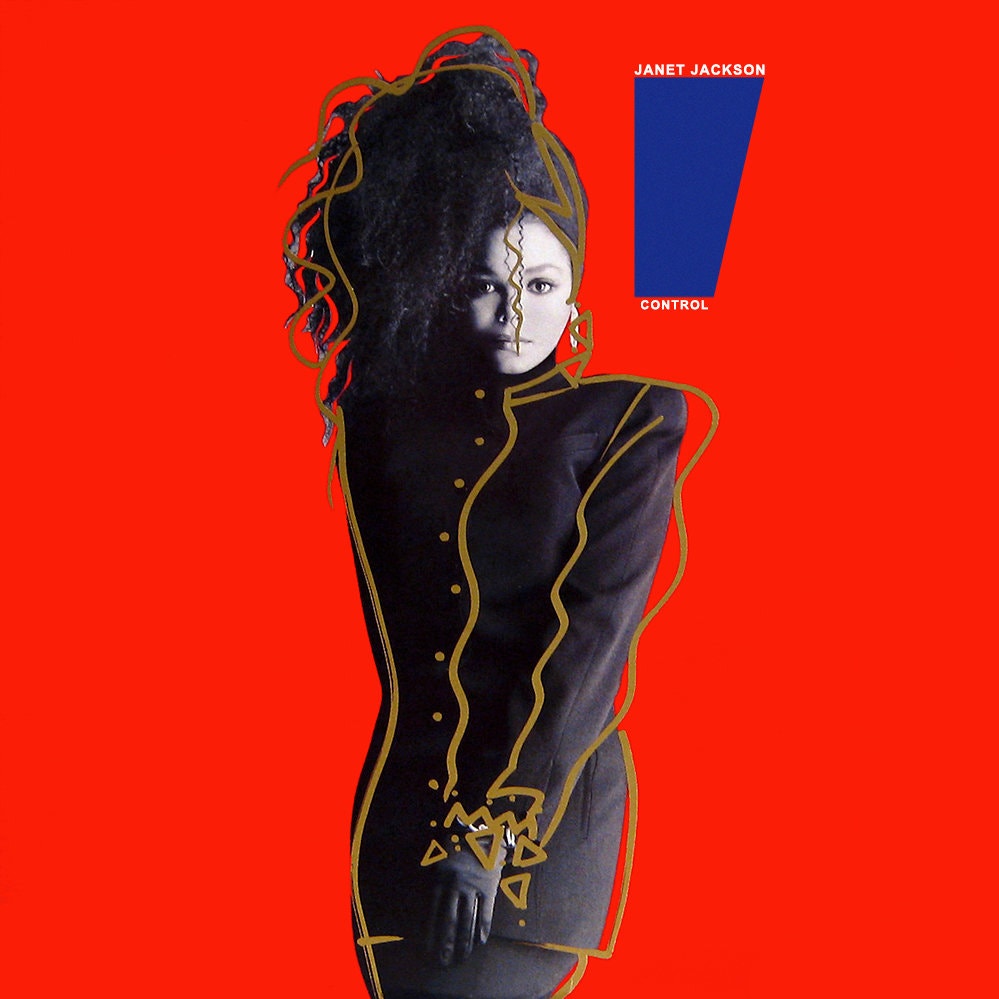

Part of the title for this piece comes from a 2014 article from The Atlantic penned by Joseph Vogel making a case for Janet Jackson as the most culturally significant femme artist of the 1980s. I think of Ms Jackson’s work and discography and it languages itself as a Manifesto to me as my thoughts melt into the shape of words. A Manifesto of being ontologically, socio-politically and sexually liberated, and of a radical self ownership and authorship of that liberated or rather, free(er) self. A Manifesto sonically and thematically crystallised with her 1986 number one album Control at just 19 years of age “Jackson created a subtle concept album, about [femme] independence—from the take-no-prisoners electro-funk ‘Nasty’ to the shimmering delicacy of ‘Let’s Wait Awhile'”. Three years later the artist would follow with what is thought of as her most iconic and influential work. The twenty track album (interludes included) released the same year as Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, the protests at Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and not to mention within the still very present affects/effects of the War on Drugs and the government funded crack cocaine crises that laid siege to Black families and communities during the 80s in America.

In his Rolling Stone cover story, journalist David Ritz compared ‘Rhythm Nation’…to Marvin Gaye’s landmark 1971 album ‘What’s Going On’—a pairing that might seem strange…But think about it, and the comparison makes a lot of sense. Both albums are hard-won attempts by [B]lack musicians to be taken seriously as songwriters and artists—to communicate something meaningful in the face of great pressure to conform to corporate formulas. Both are concept albums with socially conscious themes addressing poverty, injustice, drug abuse, racism and war. Both blended the sounds, struggles, and voices of the street with cutting-edge studio production. Both fused the personal and the political. And both connected in profound ways with their respective cultural zeitgeists.

This morning while suiting up to face and brace the outside world, I was listening to The New York Times podcast Still Processing hosted by Jenna Wortham and Wesley Morris, this specific episode called We’re Still Here For Janet was released on the 1st of February 2018—and the majority of it is dedicated to discussing the importance of Janet Jackson but also to unpacking the infamous 2004 Super Bowl event termed “Nipple Gate”. The synchronicity of this episode popping up (I listen to them at random) a week after the release of the Framing Britney Spears Documentary and Justin noodle-head Timberlake’s notes (non)apology to both Jackson and Spears (YAWN) wasn’t lost on me. In 2018 Timberlake was to perform during that year’s Super Bowl halftime show, “when I heard he was doing that I was immediately traumatised, we were re-triggered. Well mostly, it just sort of confirmed for me everything that we already knew to be true about the way this country works”. Which is to say what we—Black people—already knew to be true about the way the entire world works “because Western European civilisation is entirely organised around [white supremacy]. It’s not some aberrant ideology within the west, but rather the central ideology which has informed everything for centuries” (Bree Newsome Bass). The vastly different ways in which “Nipple Gate” affected/effected Janet Jackson and Justin is a demonstration in the destructive violence of racism, sexism and the places where they intersect:

So here’s the thing though, Justin’s back. He’s got a new tour, a new album and this new shiny halftime show to promote it all. But when we look back 14 years or so ago, thing is that event was a turning point for both Janet Jackson and for Justin Timberlake. One person’s career continued to ascend, the other person’s career essentially flatlined—and we have to talk about why that is. We also have to talk about why America was so freaked out about this event?

There’s a part in the podcast where Jenna brings up a speculated alternate possibility to how different the events, conversations and moral attack on Janet Jackson could have been had Black Twitter been in existence at that time (remember we are our own defenders and best things). How, if Black Twitter did exist then, although what happened still would have happened:

we would have been able to shape the way it was perceived, we would have been there for Janet! And we could have said ‘actually this is out of control’, we could’ve wielded the outrage machine for good—we could’ve wielded our anger in defence of Janet!