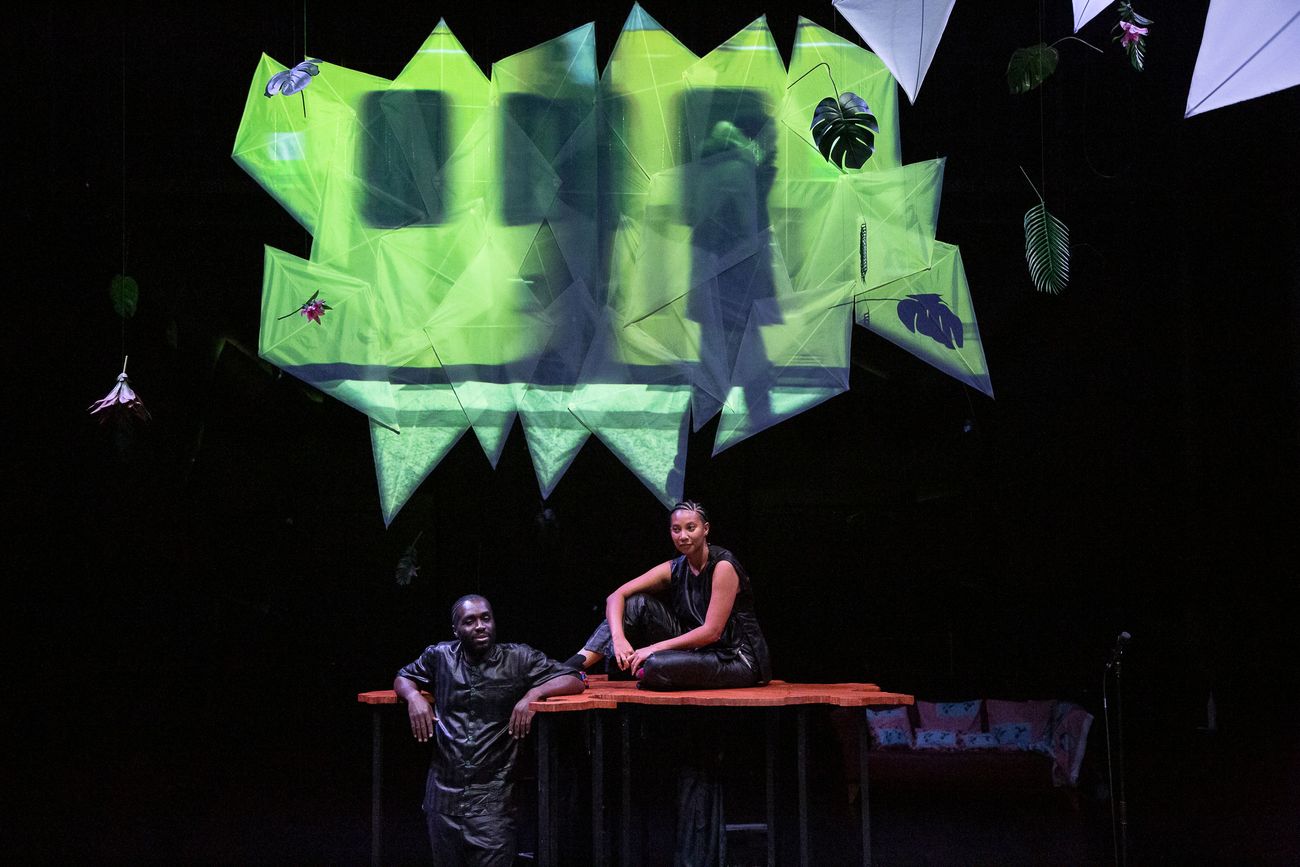

Swiss artists Cédric Djedje and Noémi Michel embarked on a residency in Johannesburg last year to advance their ongoing research project titled “Black diasporic futurities.” This interdisciplinary endeavour delves into narratives of futurity within the global Black diaspora, blending elements of documentary theatre, performance art, and Black feminist critical theory. Djedje and Michel offer insights into their residency activities and the rich experiences they encountered during their time in Johannesburg.

Cédric Djedje

Can you describe your artistic process and how you and Noémi collaborate on your pluridisciplinary projects?

I’m mainly an actor and I’m increasingly creating projects. I always create projects in collectives or collective creations. Noemi and I have been working together since 2018 on a project that mixes documentary theatre, performance, rituals and diaries. The show, called Vielleicht, looks at the struggles of African and Afro-German activists to change 3 street names in a district of Berlin called the African Quarter in homage to the German colonial empire in Africa. The show is the result of a 6-month residency in Berlin. I first called on Noémi as a university researcher specialising in post-colonial issues during the residency, and then during the show’s creation phase I asked her to take charge of the show’s dramaturgy. She became the guarantor of the conceptual balance, the historical accuracy of what we were putting forward and checking the meaning of the scenes on stage. She also co-wrote the text with Ludovic Chazaud. At the end of Vielleicht, we wanted to continue working together and develop a common language combining academic and artistic research. Many of the activists involved in Vielleicht had very strong links with Namibia or South Africa. So we wanted to continue working on the issue of politics linked to dreams and the future, but this time on the African continent.

We spend a lot of time researching the historical and political context, and while we’re at it we also think about the appropriate form in which to talk about or deal with this research. We like to work within constraints that we give each other to research texts and/or produce textual material (constraints of time, subjects, formats). We decided to alternate every week who would take the lead and propose activities, exercises, research and meetings. Black critical theory was incorporated by proposing texts or interviews with black thinkers, as well as by reflecting on ways of sharing knowledge. Noémi, for example, was very interested in conversation as a way of sharing knowledge and creating concepts, which gave me the impetus to think about what performative and scenic translation might look like in a more theatrical space or institution.

How do you plan to engage with Johannesburg as a vibrant center for the Global Black diaspora and Afrofuturisms?

Johannesburg is a vibrant centre for the Global Black diaspora and for Afrofuturisms, namely for innovative visions about technology, blackness and the future. It is the city where inequalities inherited from Apartheid cross Black politics of hope stemming from the long struggle against this regime and its afterlife. Moreover, the South African context also offers a critical perspective on the label “Afrofuturism” as exemplified by novelist Mohale Mashigo’s affirmation that “Afrofuturism is not for Africans”. Staying in Joburg and connecting with its vibrant and various scenes would be uniquely enriching for our research on Black diasporic futurities.

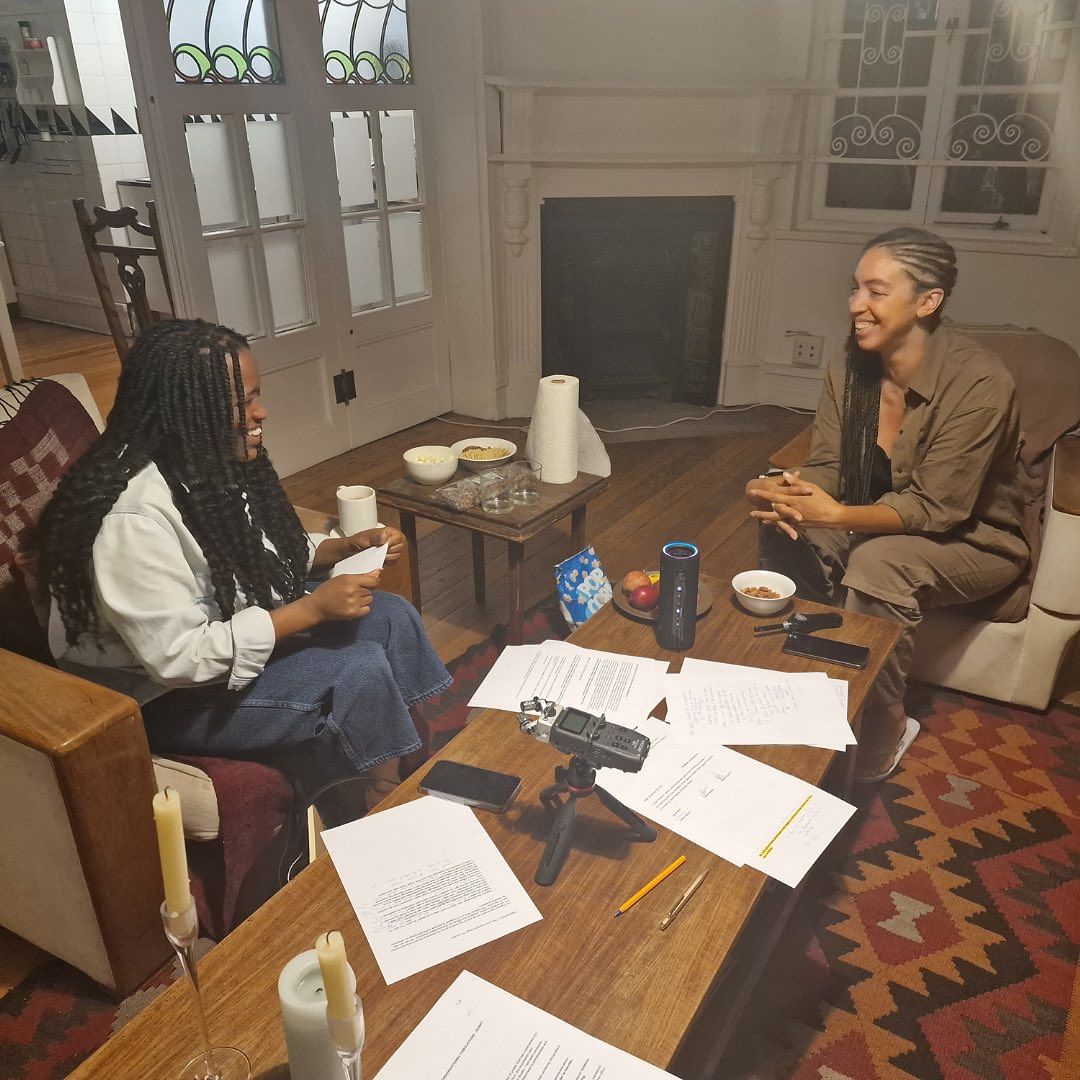

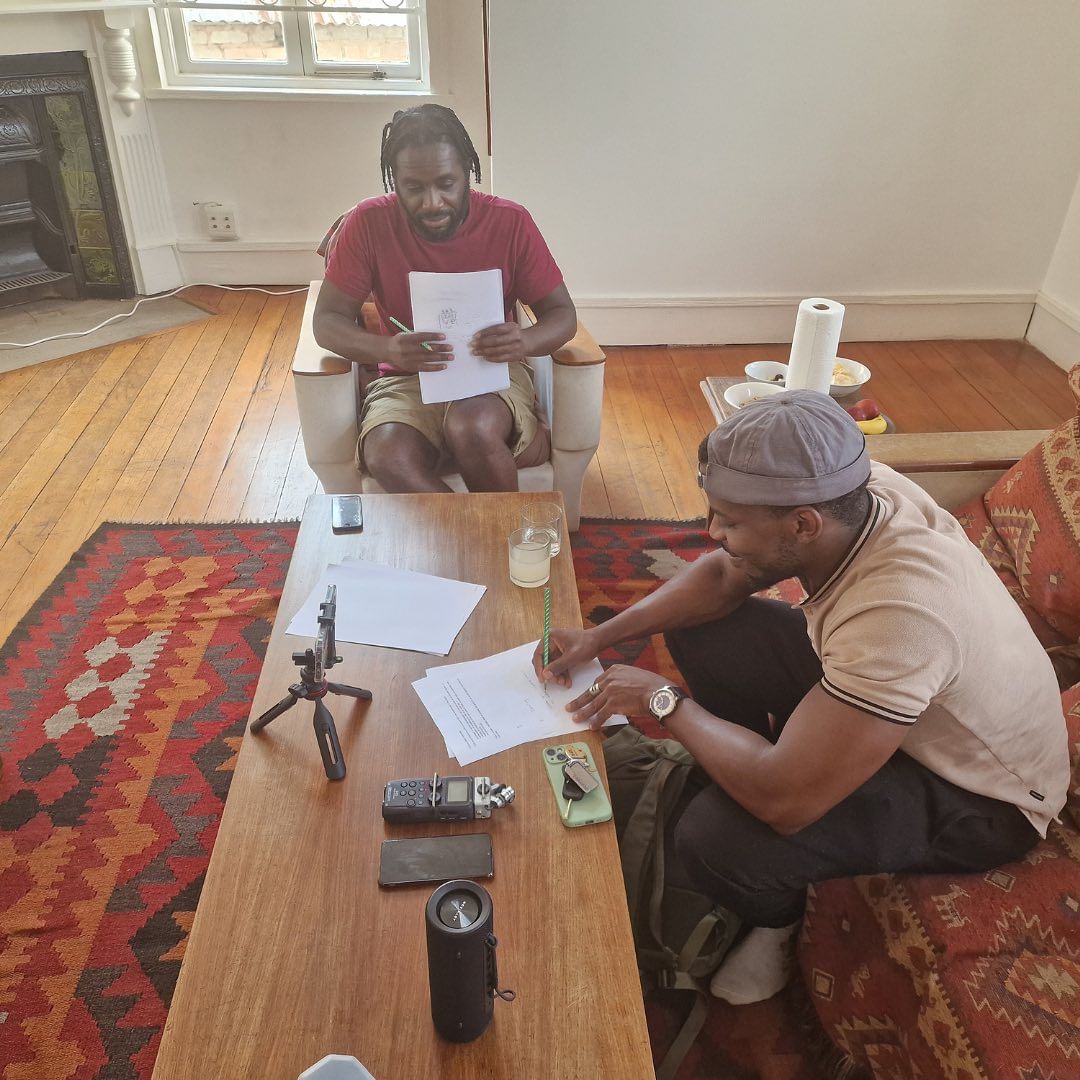

Before going, we envisioned two forms of collaborations. First, we wanted to expand our preexisting audiovisual library of Black conversations about the future. We would record interviews with artistic practitioners, thinkers and activists who deploy speculation, radical Black imagining, science-fiction or prospective thought. Our interviews would explore their specific philosophies of time and their creative methods for narrating the future.

Can you share some of the key influences on your work, both in terms of artistic influences and intellectual inspirations?

Nnedi Okorafor

Octavia Butler

Mwenya Kabwe

Noémi Michel

Thuli Gamedze

Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro

Rabih Mroué et Lina Madjalanie

Alisha B Wormsley

Marianne Ballé Moudoumbou

In what ways did these discussions shape the conference-performance “Vielleicht” (2022-23)?

In many ways, I would say enormously, both intellectually and artistically. One of the main influences was the place of the dream and the activist as a political project linked to the future. In fact, it took me a while to understand that the speeches, actions and concepts put forward by activists mobilised different temporalities in the same moment, like Marianne Ballé Moudoumbou’s (a Berlin activist of Cameroonian origin) use of the Sankofa symbol, which is a bird that flies while looking behind it, looking at and understanding the past in order to build the present and the future. I also understood the importance of joy and celebration as a political weapon and a means of reflection. This led me to ask myself what would be an artistic and textual form that would blend these different temporalities, celebration and joy in the same form.

How do you plan to connect with other Black critical thinkers and artists during your time in Johannesburg?

Thanks to Noémi’s network, we’ve already been in contact with Mbali Dhlamini and Candice Jansen, who helped us discover artists and venues before we arrived in Joburg: Rangoato Hlasane, The Forge or The Center for the Study of Race, gender and class at UJ. Jamal Nxedlana and Rucera Seethal and the Pro Helvetia team also helped us to discover artists and places before we arrived in Joburg and gave us tips on the best ways and means of communicating with local thinkers and artists.

What are your expectations for developing collaborations with local artists using performance, theatre improvisations, and multimedia installations?

We hoped to encounter other ways of creating and of mixing political and artistic issues and to gain a better understanding of the relationship to politics and the future through the history of South Africa. When I say better, the idea is to go from knowing something close to one per cent to three or 4 per cent by the end of the residency. It’s important for me to learn new performative tools and discover new artistic forms and to better understand the different processes involved in creating these forms.

It’s very important for us, following on from Vielleicht, to continue to move away from European ways of thinking and ways of creating that are linked to the European continent. It’s just as important for us to ask ourselves the question of our place as black people and Europeans, of how to get into contact and collaborate with South African artists, activists and thinkers without being in an extractivist relationship? Is this possible? How long or after how long?

Noémi Michel

How do you integrate theory and artistic and collective experiments in your work, especially in the field of critical Black thought?

I am teaching Black studies at an art school in Geneva and I always introduce my seminar by emphasizing that critical Black thought should never be reduced to its textual, intellectual, so-called “theoretical” mode of expression. Black thought is expressed through Black social movements and Black cultural practices around the globe. I evoke the Soup Joumou tradition in the Haitian diaspora: every 1st of January, we eat a soup to celebrate the independence of Haiti and the successful rebellion of the former enslaved. I learned about Black liberation, about the value of Black life as much in books that by eating this soup each year since my childhood or thanks to Black music. So, the “integration” of theory and artistic and collective experiments in my work is necessary if I want to cultivate an understanding of the complexity and the expansiveness of Black histories, lives and horizons of liberation.

Can you elaborate on your exploration of divergent understandings of antiracism in European public debates and institutions?

To answer, let me quote an extract of an article I wrote for the Journal Darkmatter: “Political anti-racists are concerned with undoing racism by transforming a set of conditions that narrow life and participation of the racially degraded, while primarily caring for the latter. In contrast, anti-racialists are concerned with preserving their moral capital of white innocence, without giving up the commercial capital provided by racist neoliberal images and narratives (such as blackface).” In Europe there is a clash between these two forms of antiracisms, between these two understanding of what we should undo: unfortunately, political antiracists – those who want to undo the colonial legacies, the oppressive systems and white supremacist capitalism – are minoritized and even sometimes criminalized as people who see problems everywhere. Antiracialists – those who want to undo the vocabulary of “race”, and put racism in the past without addressing its ongoing effects in the present and while often reproducing racism I their practices and imageries – dominate the landscape.

How do you envision contributing to the exploration of Black diasporic futurities during your time in South Africa?

Our residency took place between September and December 2023. We envisioned it as a way to pursue our collaboration around the play “Vielleicht” and expand certain dimensions explored in that play, like Black dreams and futurities. My role was to do research, gather documentation, organize our ideas and find prompts and creative common exercises with Cédric in order to generate the right questions for ourselves and then for our interviewees. We indeed conducted creative interviews with 6 Black artists (Jamal Nxedlana; Rangoato Hlasane, Mweny Kabwe, Chris Djuma, Thulile Gamedze and Mbali Dhlamini) based mainly in Joburg. We experimented with different interview scripts informed by various methods allowing our ability to project ourselves together in the near future of Johannesburg. For these experimentations, I relied on my previous work having centred Black conversation as an art form, as an important mode of knowledge production.

I also envisioned this residency as a moment of study. I am devoted to a life-long study of Black critical thought, especially of Black feminisms. Until now, my focus was very Northern-hemisphere centred (Black feminisms from Europe, the US, and a little from the Caribbean), I really wanted to be immersed in another geographical space that is key for understanding the histories and theorization of Black liberation. I am grateful that I could attend so many art, political and intellectual events while here. I think I learned and unlearned a lot. I also think that I would like to come back soon!

BubblegumClub co-founder Jamal Nxedlana

In what ways do you navigate the intersection of theory and practice in your projects?

To me, there is no way to really separate theory and practice. I apprehend theorizing as a practice, a way of producing articulations between events, experiences, phenomena, words, meanings, images, imaginaries, sounds, spaces… Also, in my view, theory is involved in practices that are deemed “non-theoretical”: ritualistic gestures, music, and movements propose articulations, so they are theorizing… I don’t think I can really answer… Or maybe I can say that theorizing is a practice that orients itself towards systematicity and abstraction, whereas practising does not always need to be oriented towards systematicity and abstraction. But I’d say that all my practices are always very oriented towards systematicity and abstraction, towards the horizon of generating the right critical notions, questions, and meanings in order to think about liberation, so this is why I identify as a Black feminist theorist.

Can you discuss your role in co-writing the theatre creation “Vieilleicht” and its exploration of Black history and dreams in relation to European public spaces?

In 2018, Cédric Djedje invited me first to act as an “academic consultant” as the play is mainly based on interviews he conducted with Black activists in Berlin fighting for the renaming of colonial street names. As the process of creation progressed, he told me that I also had to write. I had never written for theatre, it was a huge learning experience. I was fortunate to co-write with Ludovic Chazaud who is an experimented theatre writer. We organized a set of writing residencies that we called “writers’ rooms” where my role was to think about the whole structure of the play, to interpret and select excerpts of the interviews, to make sure that certain historical and political key information would appear in the text, to fact check. Ludovic would write the scenes with the subjective voices of the two characters on stage. However, as we progressed in the process, our respective roles got blurred, I also began to write certain scenes, to rewrite etc… It’s funny to witness the audience laugh on certain parts I wrote, this is something I could never experience with my previous writing.

How do you see the impact of this work on the broader conversation about decolonization and Black narratives?

I hope that this work, besides many others, contributes to open up a space of homage and care for past, present and future lives, names and voices that were, are and will be key to the constant struggle towards decolonization and more just futures.

This story is produced in the context of an editorial residency supported by Pro Helvetia Johannesburg, the Swiss Arts Council.