The arts and sciences have been separated into distinct fields. More than that, art and science, particularly in Western culture, are often positioned as polar opposites – associated with either the left or right side of the brain, different sections on university campuses, and even gendered as masculine or feminine. These fields never seem to occupy the same spaces. But Swiss-based artist and researcher, Anke Zurn, questions this inclination towards separating the fields and created a project that crosses disciplines, cultures and time.

Anke Zurn is professionally trained as a solid state chemist, obtaining her PhD at the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research. She has also studied Visual Arts at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Stuttgart. She has spent much of her career separating her work as a chemist and visual artist. But with her project on indigo traditions, Zurn decided to cross the boundaries between art and science to incorporate both her science-research practices as well as her artistic pursuits.

“My interest in indigo is related to my personal art-chemistry relation,” Zurn explains. “And how the production and use of indigo combines an artist’s and a chemist’s approach to materials.”

In August last year, Zurn travelled to Senegal as part of her residency with Pro Helvetia Johannesburg. She spent her residency primarily in Dakar but ventured out to other regions to explore indigo dye traditions in places such as Saint Louis, Tambacounda, and Kédougou. “I have already been to Senegal several times, especially Dakar as my partner is from there. So, choosing Senegal as a starting point for my indigo project came from a deeply personal and intimate place,” says Anke.

For her project, Blue Herbarium, Zurn explores indigo dyeing techniques in different cultures. She visited local artisan studios and ateliers, such as textile weaver Tëss and artist Cécile Ndiaye. She discovered different plant-derived inks that were grown and used in Senegal as well as projects on reviving leather dyeing techniques. “I learned a lot about West African tannin-containing plants used traditionally in medicine, or for leather tanning.”

The use of indigo as a dying pigment is a tradition that traces back to ancient Egypt and stretches across several cultures from around the globe throughout human history. Many countries around the world discovered indigo independently and developed their own dyeing traditions, different ways of extracting and processing the pigment, as well as their own relationship and history with the dye.

Indigo seems to hold a particular social currency. Referred to as “blue gold” in the sixteenth century during the peak of its trade, indigo, the growing, extraction, trade and even dying of fabrics, has a rich and complex history, involving slavery and abuse as well as connection and exchange.

“I am drawn to indigo’s material properties, and the related biological and cultural diversity, but also the history of indigo as a valued material, which is densely interwoven with the colonial past, and today’s post-colonial economies particularly indigo fabrics,” she adds.

However, during her residency, Zurn tested positive for coronavirus. Her hotel room then transformed into a quarantine-studio-research hybrid space. She began experimenting with dying techniques, even using other plants that have their own dying properties, and reflected on the relationship of indigo in Senegalese culture and gained insights and new ideas about using indigo in her work.

“Blue Habranium is a long, ongoing project,” Zurn says. “I hope to come back to Dakar during the harvest season and continue researching indigo traditions and the intimate relationship local communities have with the plant. The trip was far too short, and I still have much to learn!”

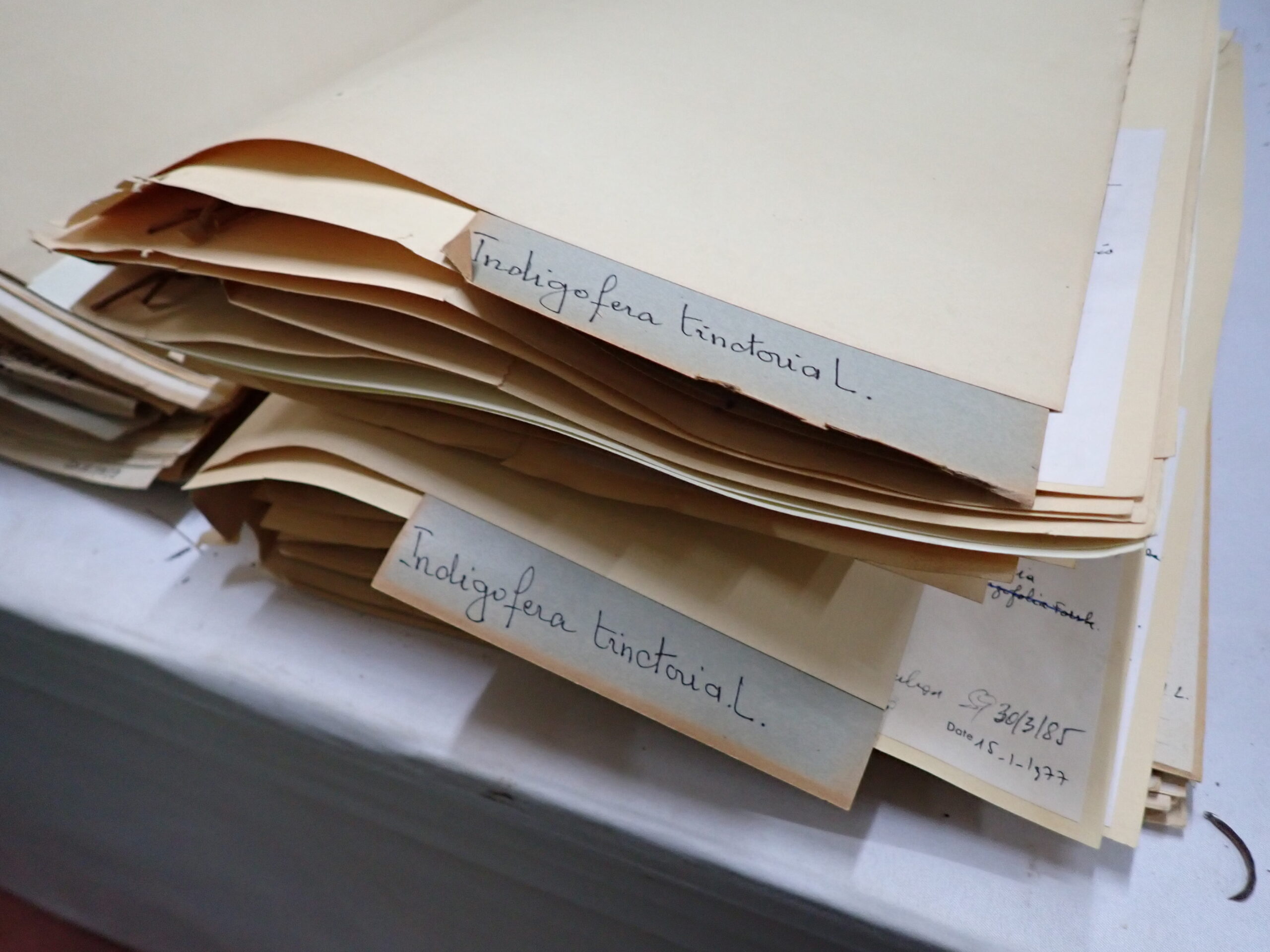

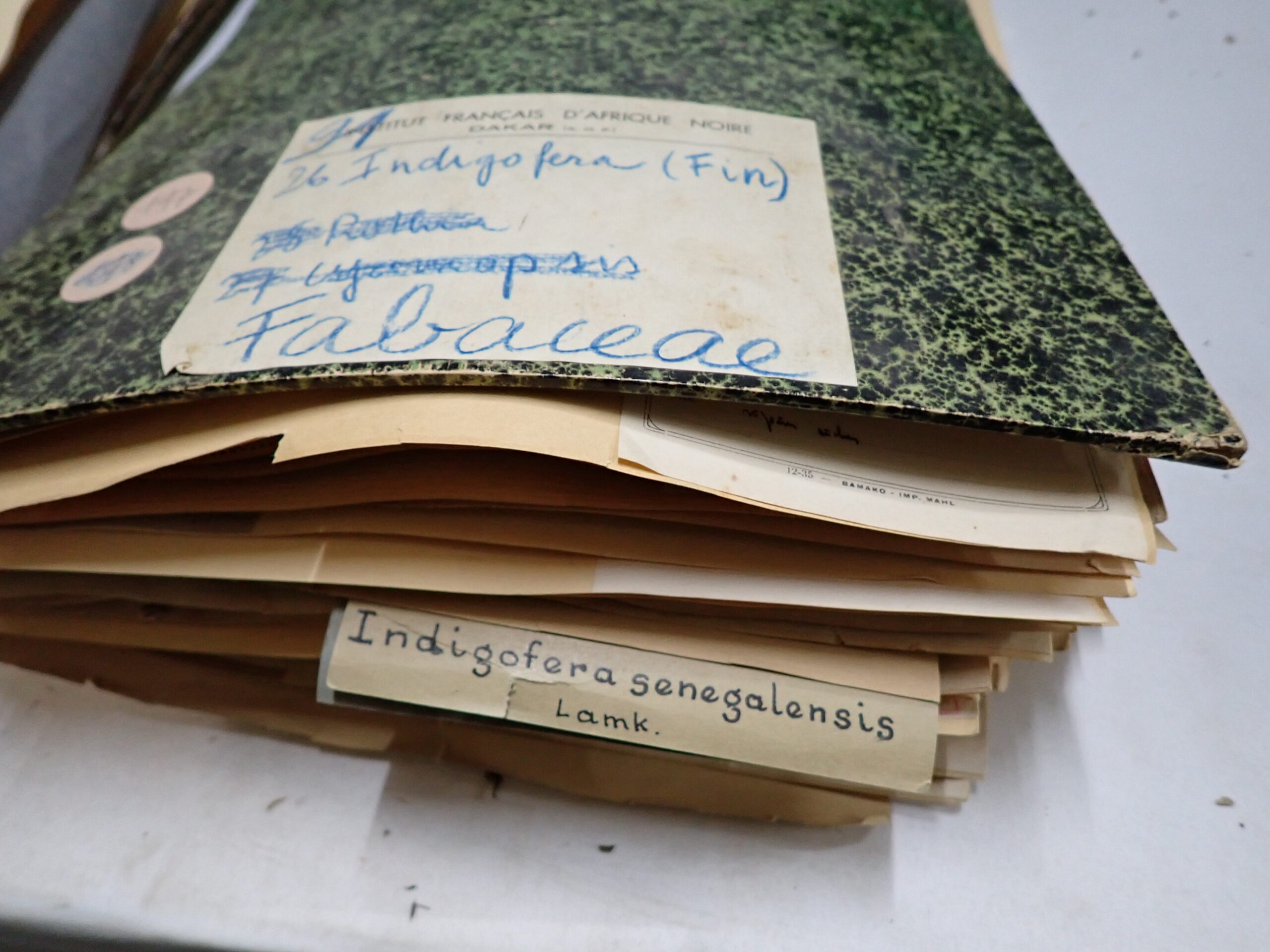

For the Blue Herbarium project, Zurn collects and preserves indigo plants to create a collection and visual representation of these different techniques as she relates them to the history and cultural practices associated with indigo dying. Zurn uses a chemical process to expose the composition and structure of indigo plants.

“I really underestimated the technical as well as logistical issues involved in the process,” Zurn admitted. “It’s not realistic to collect and process the different plant materials during a research trip. I think it would have been better for me to focus on the different indigo traditions during my residency, and then process the data afterwards. Considering the plant materials I needed for the Blue Herbarium project, it would have made more sense to grow the different plant species in my personal garden, and to process them in my studio, at the right harvesting time.”

Zurn’s residency in Senegal is just the beginning of her research project. She hopes to travel to different places to continue investigating and studying the practices and history of indigo dyeing traditions from different cultures. “I hope to one day move my art studio to Dakar and have a foodscape of sorts where the pigments can be grown and extracted all in one place.”

This story is produced in the context of an editorial residency supported by Pro Helvetia Johannesburg, the Swiss Arts Council.