Through the collaborative residency project, Luso-Linkup, initiated by the Bag Factory to connect South Africa, Mozambique and Angola, editors Luamba Muinga and Sara Carneiro bring us the digital project; Are we not makers of history?

Rendered in book format, the project brings together a group of artists, writers and makers to explore historical legacies of colonialism, civil war and apartheid. By pointing to the ways in which history and identity are a never-ending project, the book seeks to re-examine the past and our relationship to it.

Below is an interview with the curators of the project. The full publication can be accessed, here.

My first question is why the proposition of the project is framed as a question — are we not makers of history? I’m interested in the object and subject of this question. What the question is about and who it is directed to?

SARA: The title is inspired by a phrase in one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches that said “We are not makers of history. We are made by history.” We found this statement to be very interesting in how it raises questions about whether we are participants or products of our History. So the question arises are we not makers of history?

The word ‘makers’ in my opinion is key, in the sense that we collaborated with creators and we are producing content. The question we think is directed to everyone, as living people today, we are participating [in] and shaping our history but we also have the power to change the perception of the past, and that’s a crucial question that we wanted to explore.

LUAMBA: We were interested in looking at History and Identity as a never-ending project. And the best way to do this didn’t seem to be with a statement, but with a question that made [it] everyone’s responsibility to give an answer.

The issues explored by these two themes are articulated every day by each person at any time, and it is essential not to be apart from them.

Teresa Kutala Firmino, Respect, Waste and Recycle; 2020.

In a sense, the book relies on the practice of translation to exist — the necessity of translation in communicating and making meaning. But I’m also thinking about the work that artists, historians, anthropologists etc. perform as a type of translation of history, particularly in this context.

Can you tell us a little bit about what that process of translating between two languages was like in this project?

SARA: Since the beginning of the project, we acknowledged the importance of publishing this book with both languages: English and Portuguese, so we could make it accessible to the South African and international public but also to our Portuguese speaking countries, Angola and Mozambique.

So, early on we started to translate our textual material and we worked with a translator that helped us along the way. Another question was: how to translate physical artworks to the book/digital format. In that sense, the process of choosing the visuals, the layout and [the] sequence of the publication was crucial to how we wanted the work to be perceived and understood.

We tried to give the artworks the central focus of the publication, and pair them with text that complemented them conceptually. Also, we wanted to take advantage of the digital medium by publishing video works that allow the reader to have an almost full experience of the work.

LUAMBA: It’s interesting what you say about the “work as a type of translation of history”. The publication is really centred on that, on how to translate individual experiences into History. History has always been a kind of translation of events, many of them relegated to official structures and few structures of power over the majority. It’s also interesting that at one point the idea of the “end of history” [was] theorised by many academics.

The central question of the book is to understand if these artistic, personal, affective fragments are not part of an assemblage in a History in constant movement; the one from which no one has stopped yet, to define all its lexicons and attribute a single language to it for everyone.

Marilú Mapengo Námoda, Memórias de uma língua de cão; 2019.

Can you speak to us about the form of the book? The textual contributions were quite broad and rich — Lizette Chirrime’s lyricism vs the interview format with Teresa Kutala Firmino, or prose with Luís Santos for instance.

What were some of the decisions that went into the concept of how the book would look and feel?

SARA: Our approach to this book was to create a dynamic and captivating publication that allowed the reader to emerge in the artworks and the questions presented. We invited the artists to collaborate with us, not only by providing images of the artworks, but also by sharing a textual intervention of their choosing.

We were looking for different ‘text’ formats that would capture the overall feeling, and their personal approach to the concepts. We wanted to have material that could bring conceptual depth, but also a poetic approach that would leave the reader meditating on it.

LUAMBA: As Sara said, we wanted the texts to reach a kind of “performativity”. So, the use of experimental and less formal formats seemed relevant to this project.

Can you tell us a little bit about the Luso-Link Up? Is this the first publication to come out of the project?

SARA: Luso-Link Up was a curatorial residency designed to help young curators based in Angola and Mozambique. At first, the program was to have a 1-month residency in Johannesburg, but because of the pandemic, the Bag Factory ultimately decided to do the residency online.

Going virtual gave me and Luamba more time, where we spent more than 3 months discussing and working on this publication. The publication was a personal choice of ours; we felt that it was the best format to communicate and bring these artists/writers together. However, if the project continues the participants [could] choose another approach to the residency.

LUAMBA: Our participation was the first in the Luso-Linkup project. We don’t know yet if Bag Factory will continue with the program, but it would be of enormous interest if it were possible. And if it does that, it could connect professionals from other PALOPS countries.

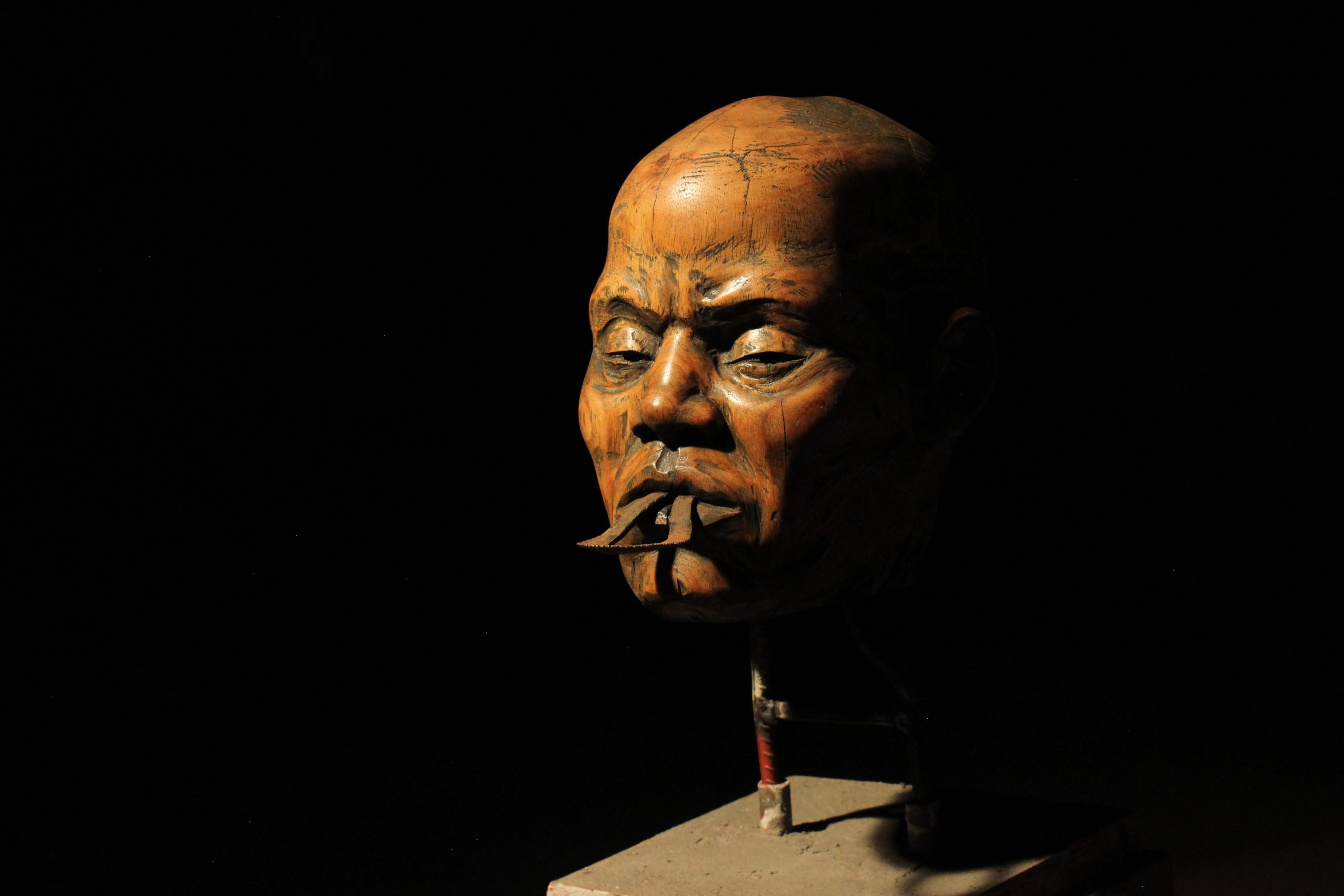

Luís M. S. Santos, Bite Your Tongue; 2020.

I recently learnt of the PALOPs. The six Portuguese speaking nations in Africa —including Cabo Verde and Guinea-Bissau. It made me think about how language isn’t always the only restraint in reflecting on our shared histories of colonialism.

Can you speak to some of the challenges that you believe present themselves in relation to South Africa, Mozambique and Angola, for instance, beyond language — if any?

LUAMBA: I think this is a very cross-cutting issue. If we think in terms of regions — we can situate the question of borders in this topic — by seeing how communities have [been] fragmented throughout history and, in that, instead of thinking about their identity issues resulting from these fragmentations, they prioritise concerns that could nullify this. The easiest way to answer you might be to mention national politics.

SARA: I think there are many challenges. Between language barriers, borders, long distances, lack of resources, all of which result in poor communication and awareness between countries.

We could all benefit from exchanging experiences, and maybe this way we could have a more complete sense of history and how we are linked. Maybe that’s why initiatives like this residency are important, to build more bridges between people. Nevertheless, the art community has the ability to constantly search for new ways to connect.

I’m interested in how memory is not only temporal but also spatial. How it is tied to place in very complex ways. Toni Morrison speaks of it as a re-memory of place. Can each of you reflect on the art landscape in Angola and Mozambique today, given these shared histories?

LUAMBA: If you look at the practice of each artist in the publication, you can get an introduction to how this spatial perspective of memory is so settled. Each reflection shared by the participants from Mozambique identifies with the practice of various artists currently on the scene in Angola.

For example, Helena Uambembe and Teresa Firmino, who are Angolans born in South Africa, have many memories and reflections on the common past of Angola, South Africa and Namibia.

SARA: As two countries that were colonised by Portugal and have had long-lasting civil wars after independence, artists within Mozambique and Angola often take on similar questions. I’m also interested in how the publication introduces two different generations.

An older one that lived through the independence and civil war, as we see through the photographs captured by Rui Assubuji, and a younger generation, that although they didn’t necessarily live through the conflict, they feel its impact and how it has shaped their surroundings, as Tavares Cebola describes in his text “In the shell of silence and oblivion”.

I feel that these younger artists are eager to learn and reflect more about their history, and they are not afraid of turning some stones to deconstruct and understand better who they are and where they come from.

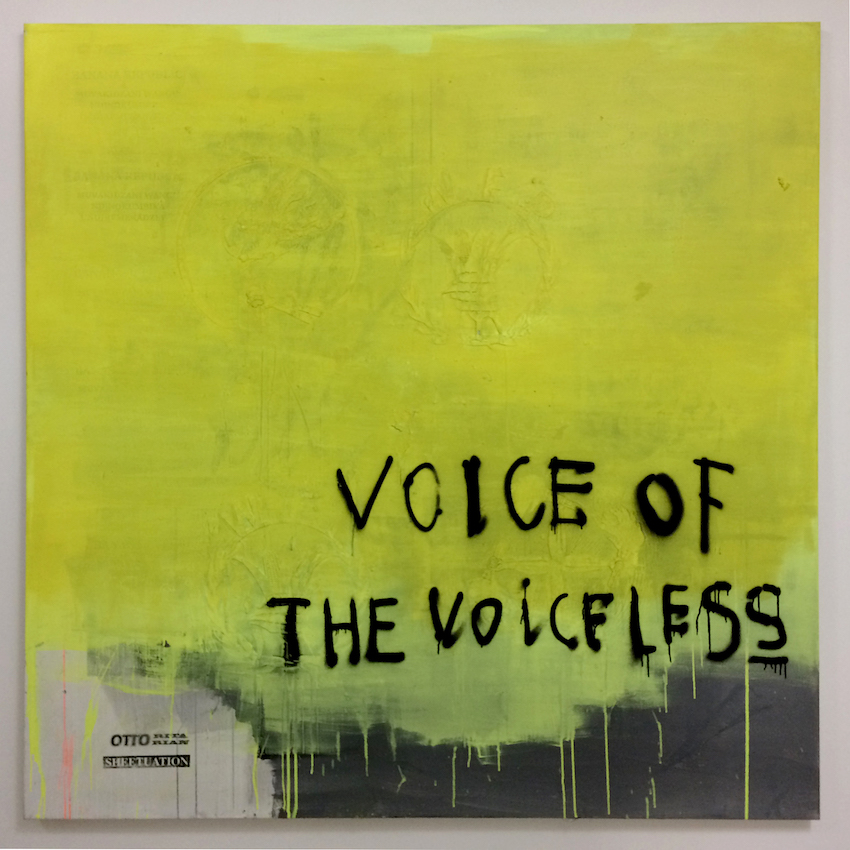

Yonamine, Sheetuation Town IV; 2018.

Contributors include:

Sara Carneiro, Luamba Muinga, Tavares Cebola, José Luís Mendonça, Yonamine, Teresa Kutala Firmino, Rui Assubuji, Marilú Mapengo Námoda, Luís M. S. Santos, Lizette Chirrime and Helena Uambembe.