Nearly a year ago, I spent a warm afternoon with one of my heroes, renowned photographer Roger Ballen at his Inside Out Centre on Jan Smuts Avenue. It’s taken me that long to finish this text, partly because the fanboy in me wouldn’t let me observe his creative process objectively. With over five decades of artistic practice, Ballen’s oeuvre commands respect and elicits reactions so effective that our encounter sent me into a months-long existential conundrum from which my dear reader, I am only just now emerging.

Roger Ballen is an American, born in New York City, in 1950. He has been interested in art since he was young and was initially drawn to photographing elderly men, but he went on to study psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. After travelling through different countries, he arrived in South Africa, where he met his future wife Lynda and settled permanently. An artist whose bond with Johannesburg began in the 1970s, one could argue that his work could be considered South African art, which I am in the business of critiquing.

I first fell in love with Ballen’s work in London sometime around the mid-2010s. Ballen’s art is transdisciplinary, merging visual art, theatre, film, and installation, with themes of psychology, biology and surrealism. Often featuring marginalised (often mutated) subjects in strange settings, the grotesque is what draws me to Ballen, though I recognise the flaws. Supposedly devoid of a political agenda, Ballen’s work aims to reflect the subconscious and transform reality.

Upon arrival, Amanda Ballen, daughter of Roger Ballen, led me through the Inside Out Centre for the Arts, which opened in March 2023. Her illuminating tour seemed well rehearsed and organised and at first, the family angle was an unexpected treat. Learning about the artist through watching his descendant proudly perching her own legacy on his. Reflecting on Ballen’s artistic philosophy, Amanda stressed that the Inside Out Centre is dedicated to exploring psychology and encouraging introspection and self-analysis, as well as diversity and the democratisation of art. Curious.

Designed by JVR Architects with a Brutalist aesthetic, the Centre is spacious and well-lit, with office spaces on the top floor and plenty of outside space. But from the architecture to the leadership and even the content, the err .. elephant in the room at the Centre is whiteness. Black figures are depicted mostly as aides or servants to white figures in the historical imagery. Generally, Ballen’s human subject is white. The only other subject is animal. This could be generative if it were uttered outright, but it is not.

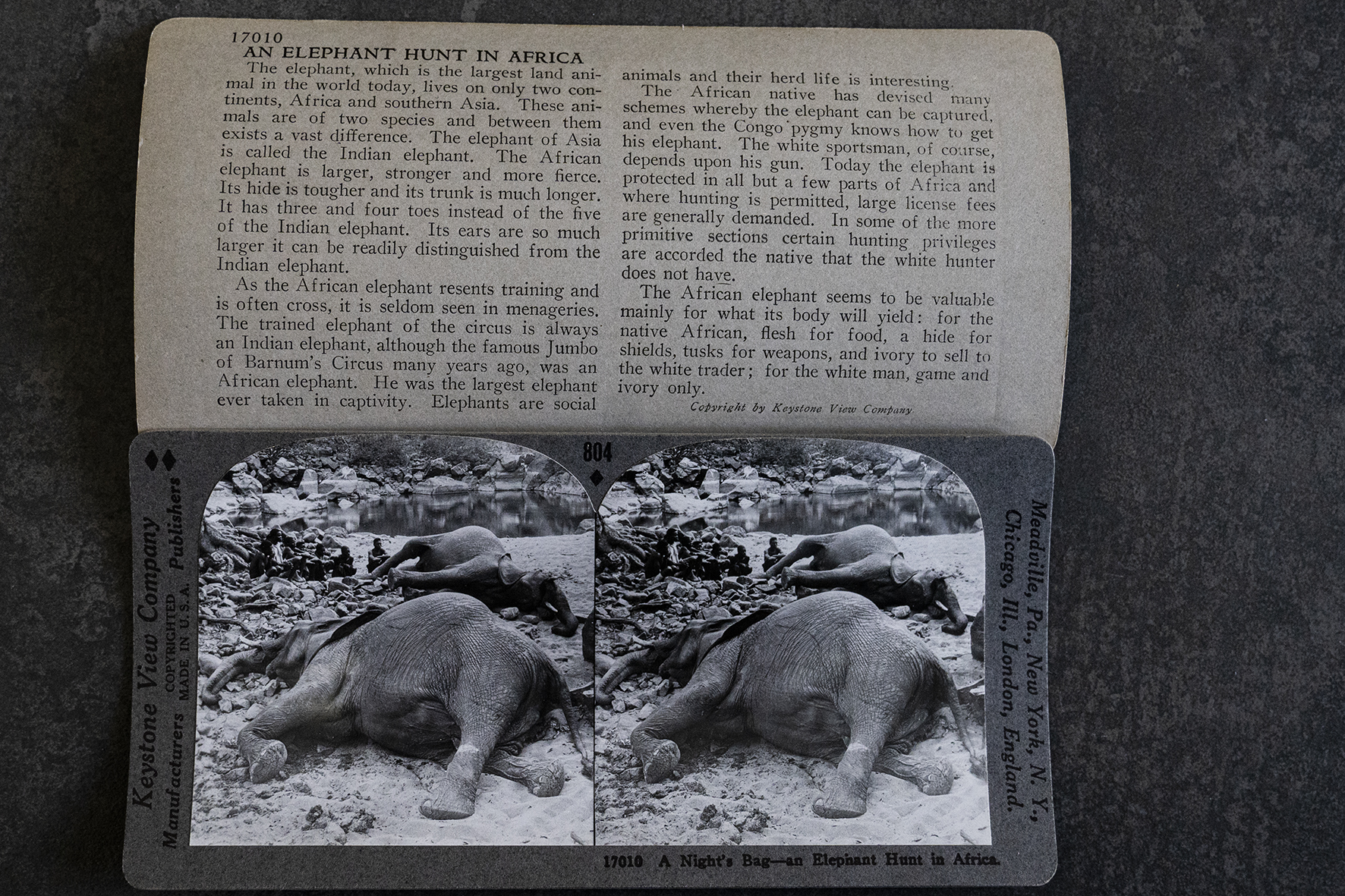

Apart from the formal presentation upstairs, which takes an ethnographic tone, the rest of Ballen’s inaugural exhibition End of the Game exudes comfortable chaos. Curated by Ballen, it explores the historical and ecological impacts of African hunting expeditions during colonialism. Featuring photographs, sculptures, installations, and Ballen’s distinctive creatures like taxidermy animals and mangled mannequins, the exhibition evokes a strong sense of the grotesque. A theme that permeates the exhibition texts and signage.

When at last I was introduced to the artist himself, he was nothing like I had imagined in all my years of fandom. His work made me picture some menacing, maybe mousy man, some creep holed up with his despicable designs. But in front of me stood a rather handsome man of stature, put together and fitting the family firm environment I had found him in. There seemed strangely nothing especially grotesque about him at all. When he spoke, in his subtly Yankee accent, he was assertive, perhaps even slightly cocky, but not at all grotesque.

We walked to the far end of the exhibition space and sat eerily close to one another, separated only by one of his menacing mutants. Through his body language and tone, I could sense that he had no high expectations of me. He had no clue how much I loved him—his work that is. He did not sense my intoxication, being so close to him. I found this dynamic in itself already rather grotesque and I leaned into it. The first question I asked was about the grotesqueness of his work and how he thought it was perceived, but we did not seem to see eye to eye on this line of questioning. He answered:

“The first thing is … when we talk about people’s response, this is very complicated. Firstly, you can’t get it into anybody’s head … So, people’s emotions are very complicated. And to be able to put them in a box and say, “Oh, uh, this makes them scared.” Well, what do you mean by scared? … Ultimately, uh, the response to the museum, which is most important for me … I’ve had a lot of people here who’ve never been to a museum in their whole life … And they are so, uh, happy that they came here. They’re so enthusiastic. And so positive.

So … this is what makes me most happy … people who have no understanding of art, museums, anything to do with what I do here, are overwhelmed and hug me sometimes. Sometimes they even cry; they’re so happy they’ve been here. They all take pictures. And other people who see a lot of art thank me for what I’ve done here. So, I’m not getting any of the responses that you’re talking about. Even if they feel terrified, they thank me for bringing this up and making them feel something towards what we’re doing.”

I listened intently, hoping for something darker to emerge. Desperately wanting to move away from the clinically positive messaging, I critically questioned Ballen about his use of taxidermy, intending to spark debate about the moral implications of reappropriating animal remains. But Ballan clarified that he did not kill the animals used in his installations and that was that. Rather than the dark, anarchic experiment I had hoped it would be, End of the Game was beginning to come across as not only peachy but also quite preachy.

I probed him on the ethical implications of presenting End of the Game in present-day Johannesburg, given that it was Westerners who promoted mass game hunting and the subsequent decline of wildlife species on the continent. Ballen responded, “I mean … Look (at) what you wear. Look (at) what you eat. Look (at) what you drive. Everything you do is destructive … It has nothing to do with Africa or anything else. It has to do with your behaviour and my behaviour … What you see here isn’t just an African problem, it’s a problem of humanity. It has nothing to do with race, colour, creed. It’s human biology.”

Fair enough. To this day, the World Wildlife Fund states that about 20,000 elephants are poached annually for their ivory, with SA alone recording 1,000 rhinos killed in 2020. Despite concerns, countries like South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Tanzania remain popular destinations for international trophy hunters and illegal wildlife trade persists unabated. But while End of the Game nobly defends Africa’s biodiversity, its removal from its current context is still problematic. Ballen’s benevolent mission could benefit from a more holistic perspective.

My admiration for Ballen endures and there are works in this exhibition that prove his prowess as a portrayer of South African culture. The Shack, with its perfect mix of realism and absurdity, is one such example. But I needed to sit uncomfortably close to him to recognise Ballen’s blind spots. His aversion to current social issues and distinctions, many of which happen to have racial implications, particularly in Joburg, mixed with the Centre’s superficially inclusive messaging does raise an eyebrow or two—even the institution’s name and appointment-only policy prompt reflection on the precarious balance between inclusion and exclusion.

Founded in 2007 and later rebranded as the Inside Out Trust Foundation, save one member, Roger Ballen Foundation’s board consists of Ballen’s family; since it opened, the Centre has mainly platformed one artist—Ballen himself; frequently, his texts and tours are by his daughter. Sadly, Ballen’s albeit commendable cultural enclave, in the context of Joburg, is a painful reminder of the implications of wealth and privilege—the same forces that led to the destruction of Africa’s wildlife. Even as an avid Ballen enthusiast, the Centre’s murky meaning makes me feel like an outsider in my own messy metropolis.