When you ask someone how they are doing, it is not uncommon to hear one of two responses; “I’m fine” or “I’m so busy”. Busyness is a currency to value worth, busyness as code for “I don’t have time” or more appropriately “I don’t have time for you”. We are all too busy, escaping each other and escaping ourselves.

The posthuman speed of circulation means that the world now escapes our capacity for attention and we’ve lost our time for otherness, and therefore ourselves. Under the present dispensation, connection is defined as the functional relationship between formatted materials or components. Via networks, human relations are reformatted to the pure syntax of the operating system. – John Kelsey, 2012

In a new participatory exhibition (and partial fulfilment of a degree in MA Fine Arts at Wits University) taking place at the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG), Johannesburg based artists and photographer Anthea Pokroy explores the intense connections between belonging and alienation.

I interviewed Anthea as she was preparing for the exhibition at JAG, which will be open until 21st April 2019.

I’m interested in the inherent contradictions within this word; belong, when it means inclusion and when it means exclusion? If some people belong, who does not and why?

Yes, for me the contradiction lies in the presence of the word ‘longing’ within ‘belonging’. It makes us question whether belonging will ever really be a possibility, or if we will always be left with the unfulfilled longing to belong. Belonging connotes togetherness, community and inclusion, and so in its very nature highlights its opposite – those who don’t belong, those who are excluded, the ‘unbelonging’, the ‘other’. Therefore, there is a cost to belonging: in order to maintain these boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’, we must conform, assimilate, be fearful, and keep to ourselves.

My work is interested in moving away from ‘belonging’ which is attached to these polarities, to the more nuanced, affective term ‘be-longing’. How can we reimagine be-longing as something that is more fleeting, temporal and relational than belonging; something that exists in the space between? The idea of a sustained and permanent belonging is an impossibility, owing to our constantly shifting and changing subjectivities or identities, and so I see the potential and legitimacy of belonging for a moment, in a moment.

I love how you deconstruct the word belonging…. carrying it through all the way to home, to longing and finally loneliness.

a) what is home to you?

b) what is your relationship with loneliness?

I see belonging as being ‘at home’ with yourself. Of course, ‘home’ also refers to the place or space you share with other people that make you feel that you belong. But I think the most important and most difficult thing is to feel ‘at home’ with yourself; to be at peace, in comfort, in love with yourself. I think when that is absent, that is when loneliness emerges. It is a common thought that loneliness does not mean being alone: one can feel lonely in their solitude or lonely in a crowd. It is a disconnect from where you are at that moment – either from yourself or from others. I often feel lonely when I feel that I can’t share my thoughts, feelings or experiences with someone – not because there is no one else there, but because it’s almost impossible for another person to ever really know what another is feeling. Sometimes I feel lonely when I am alone and I do not know what to do with myself, and so I often resort to filling my space with the Internet, social media – anything that allows me to escape my own thoughts. I think it is so important to be mindful and present and for us to learn to be with ourselves.

You refer to this era as the “post-relational” era, what do you mean by this?

The art critic John Kelsey, introduces this term in reference to ‘relational aesthetics’ or relational art, an art practice in the 90s which emphasised human relations and community-making as its medium. However, with the over-consumption of technology, our human relations are being disrupted and diffused. Technology optimistically promises us connection, and thereby, belonging. The paradox is that this connection is often no more than a material network, and our human relations are disconnected and fragile. We can see this clearly in our social environments where people are more obsessed with being on their phones, or taking photos to share on Instagram, than they are talking to each other and savouring real-life experiences.

“the act of being lonely together” – what do you believe happens when we are in this state? What does it mean for our relationships when we create spaces of being lonely together?

Loneliness can feel like an incredibly isolating experience. When you are in it, you feel utterly alone and that nobody else feels the way you do. I imagine that a ‘collective loneliness’ can ensue when people share their experiences of loneliness. Being lonely together may allow for a sense of identification with another. And perhaps, that moment of recognition in another’s experience – seeing myself in you – could promote a sense of momentary fleeting belonging? I initially started this project to explore my own experience of loneliness. I thought there may be a sense of healing or catharsis that emerges through hearing other people’s stories of loneliness; knowing that you are not alone in this feeling. While there is certainly an element of this, there is also a heartbreak in knowing others’ suffering.

In a culture where we romanticise mobility and individualism, what does belonging look like in the future?

The world is most certainly changing in the way that we form community. We are no longer reliant on our village, church or nation to fulfil our needs of belonging. We are able to find our kin online, globally, and with unconventional criteria. Perhaps belonging need not be thought of as ever-lasting and sustained or confining and prescriptive. The fixity of this kind of belonging is fraught, complicated and fragile. What be-longing offers is alternative, newer possibilities of forming connections, communities and collective identities. Perhaps more ethereal moments of connection and belonging can affect long-term change? Having a conversation with a stranger about loneliness could be an example of this.

Can you explain to us what the exhibition at JAG will include?

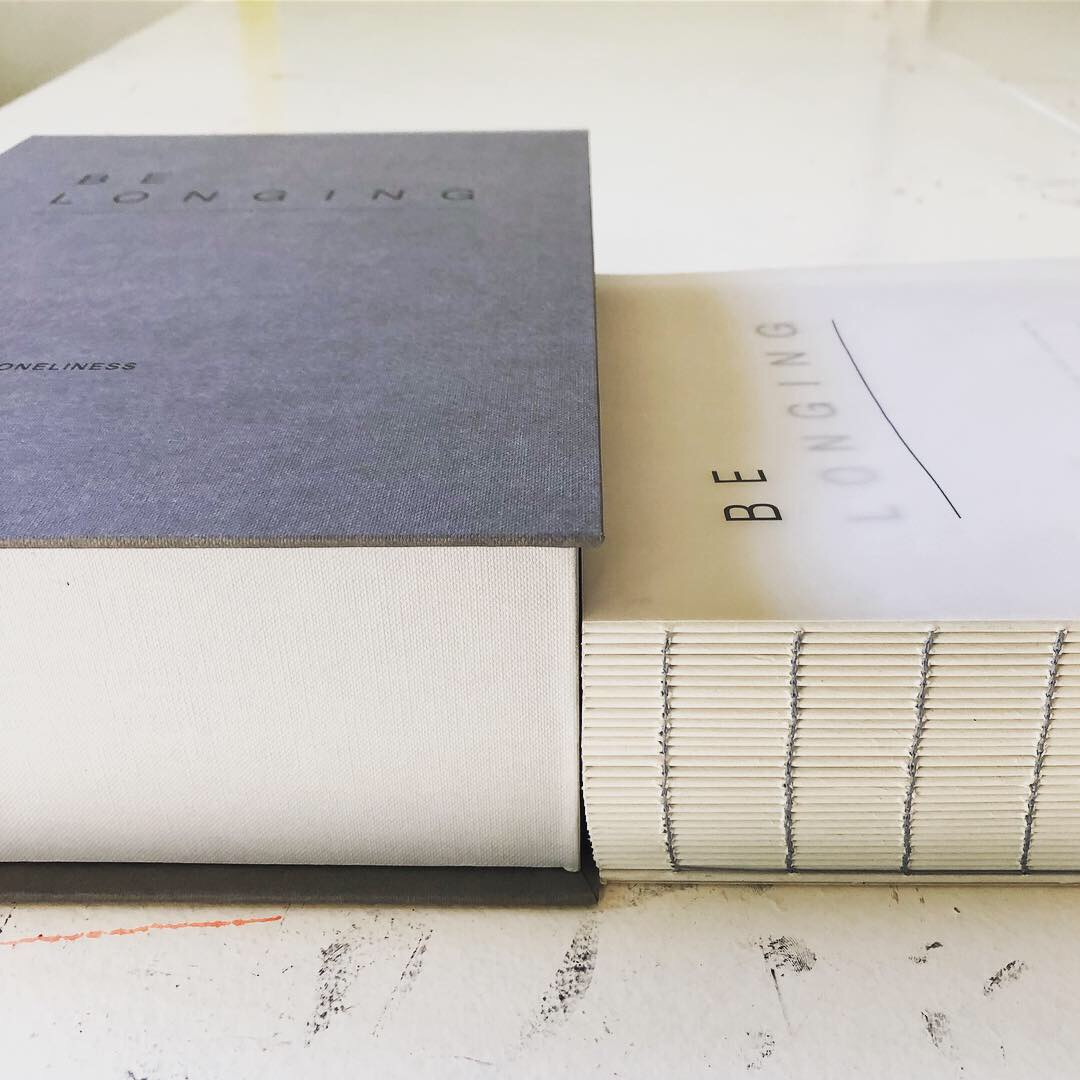

Over the last two years, I have staged six performative interventions (or ‘situations’ as I call them) in different scenarios – in public space, online, in a gallery and in a studio – where people engaged in dialogues about loneliness. Each iteration was different and brought about its own set of complexities, difficulties and potentials. The exhibition consists of a series of descriptions of these situations, which were themselves artworks, as well as a book with transcripts of 257 interviews collected over the six situations. There are three copies of the book, thereby encouraging multiple viewers to sit and read the book at their own leisure. The book comprises 1120 pages, and so is thick and heavy and hard to manage. The weight of the book suggests the weight of the stories, and the act of navigating this awkwardly large book implicates the viewer in the difficulty of the topic.

The first thing that the viewer sees upon entering the exhibition space in the basement of JAG is this turquoise neon sign, that reads ‘BELONGING’. The sign is interactive in that when two or more people sit on the bench in front of it, the whole word ‘BELONGING’ shines bright. However, when there is only one person, or no people in front of the sign, the ‘BE’ will fade and leave the word ‘LONGING’. This title piece of the show alludes to the antithetical notion of be-longing, and emphasises to the viewer that belonging cannot exist without longing.

The sixth situation, which was video recorded in a studio, forms part of a video installation in the exhibition. I attempt to cultivate a participatory and affective element through the presence of two conversation chairs between the two-channel video, which are projected on opposite walls. By asking only two viewers at a time to sit in the same chairs that are present in the video, is to ask them to connect with the narratives on screen and, in the gaps of narrative (when there is a blank turquoise screen), to consider echoing the experience on screen with the person sitting next to them. The viewer’s participation in this work is minimal and subtle. It is about the physical proximity to the person next to them (their bodies are literally touching, shoulder-to-shoulder), being alone in the room together (only two people at a time can enter the darkened room), and about engaging with the stories of loneliness that transpire before them.

It is important that this exhibition is participatory, in the sense that the works can only be experienced through an active engagement with them: paging through the interviews in the book; waiting your turn to enter the video room; sitting intimately next to another person and watching the stories; sitting on the bench alone or together to trigger the ‘BE’ in ‘BELONGING’ neon.