Warning: This article contains sensitive content that some may find graphic and explicit

Recently, I came across some texts and reflections on the work of Clarice Lispector. The celebrated author produced most of her work in Brazil, where she lived from the age of two until her death in 1977.

Born in the Ukraine, Clarice always felt like a foreigner, even though she was naturalised in Brazil.

Her works do not directly deal with the immigration traffic we live in today — with more than a billion people trying to leave their countries of origin — her literature does not address the process itself however, it addresses the feeling of being a foreigner at all times; the feeling of the estrangement effect of a being before this sociocultural cycle — a feeling of not belonging to the worlds one inhabits.

By thinking of the formation of art as a product far from works of contemplation, landscapes or simply a portrayal of what the eye sees, we can arrive at what we call contemporary art today. Art has become and always has been movement, it is astonishment at reality — epiphanies.

Art alerts us to banality, to breaking the obvious and predictable. Art employs us to perceive or to see the perception of what we have inside and around us. Everything that has already been concluded, finished or finalised does not interest artistic practice, it is the movement that grabs it. It serves us to document and register points of view.

The Russian formalist production alerts us to this question of strangeness and the perception of the same. In the book ‘Art as Procedure’ by the literary critic Viktor Chklovski, Chklovski discusses the concept of ostranenie, which in its literal translation from Russian brings us closer to the word “strangeness”. The author expands that in “strangeness” is something essential to artistic practice. “Art is the means to feel the becoming of the object, that which has already ‘become’ does not interest art”, Viktor Chklovski states.

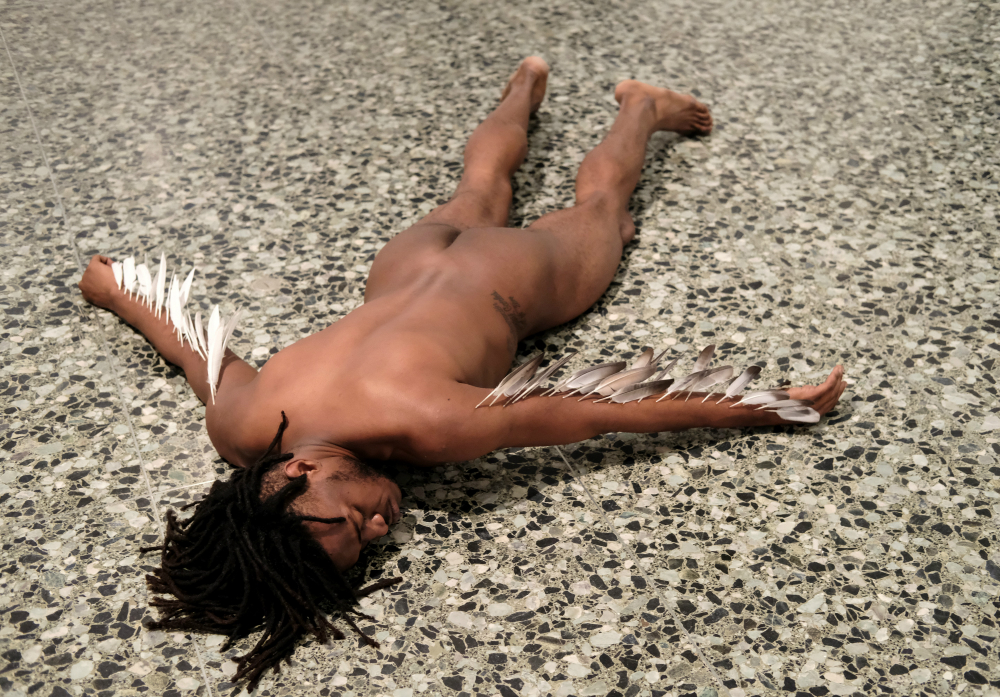

The state of ‘becoming’ — in the sense of a verb in progress — of being born, building and destroying is the artistic state at its purest. It is on all of the above and its connections that we arrive the work of Carlos Martiel.

The artist, who began his work in the performance field in 2007, lives and works in New York and Havana. Born in Cuba, he graduated in Havana from the National Academy of Fine Arts San Alejandro and during his training he studied at the Cátedra Arte de Conducta, which was directed by artist Tania Bruguera. His works and the record of his works are spread all over the world, in various biennials, museums and public and private collections such as the Guggenheim in New York.

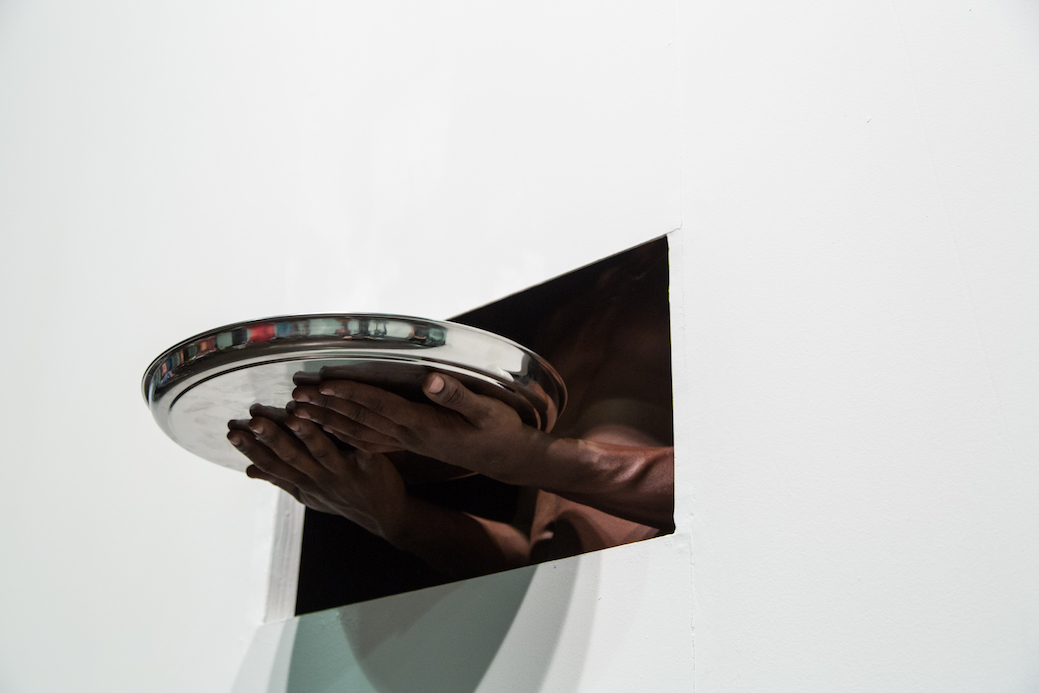

His works, even before being performative, already inhabited the experimental artistic field. When he drew, he did not use traditional materials such as pencil, acrylic or oil paints — he used charcoal, vinegar, beeswax and his own blood. It was exactly in his blood dripping on the paper that he realised that his own blood could be his subject, realising the ability to work with his body as matter and support.

His career developed a lot due to his anonymity, performing his first performances in public spaces and developing his artistic performative practice. Today, his performances have been performed all over the world.

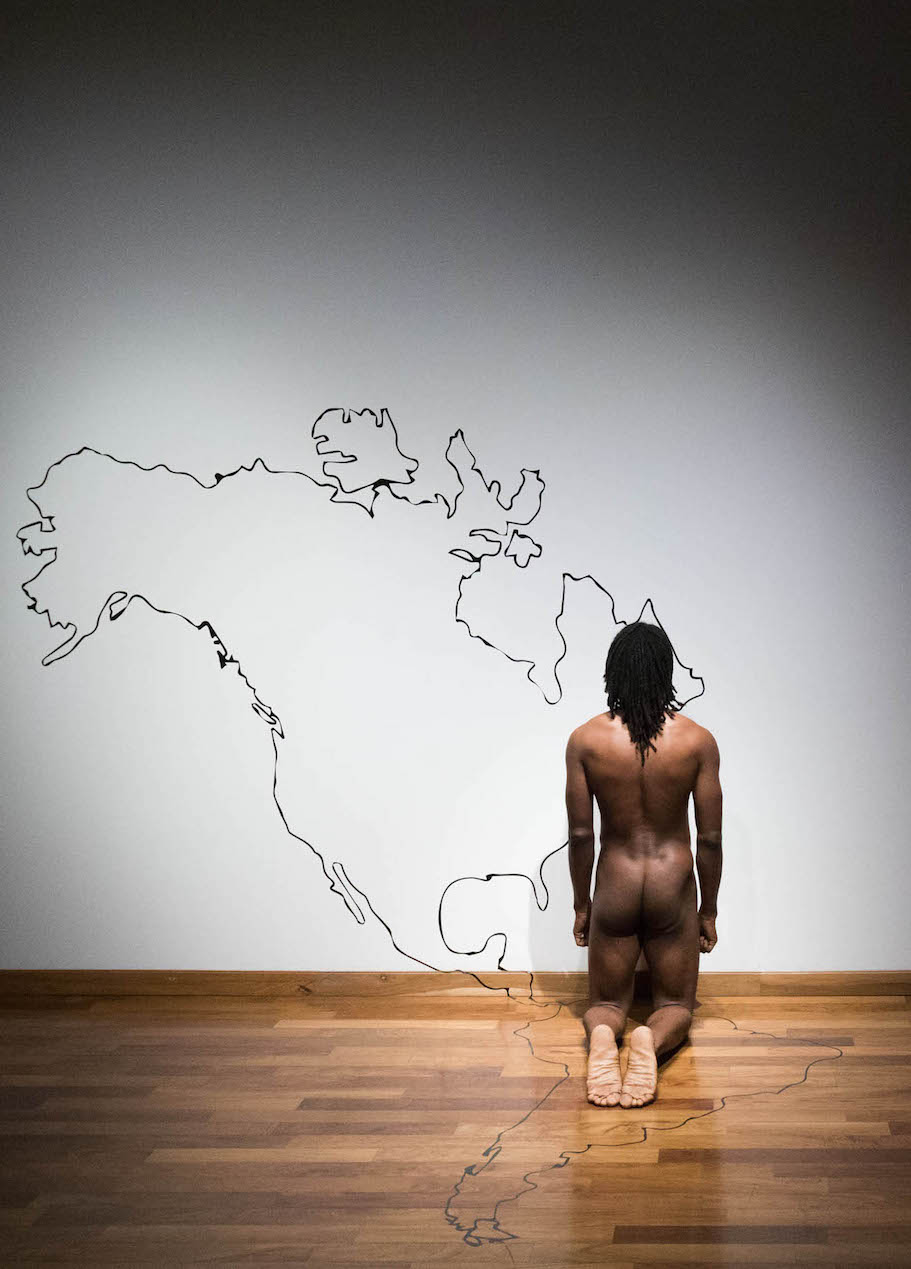

Martiel possesses and performs an art that is entirely and essentially political. His themes addressed relate directly to immigration, racism, homophobia, xenophobia and the abuse of power by political authorities, especially in Latin America. Martial states,

Art that does not express, refer to, allude to, reflect or propose a change in reality and the oppressive circumstances that specific (usually racialized) bodies experience on a daily basis, cannot be called political. My art is absolutely political. I couldn’t think of doing anything else because I was born in Cuba in the 1990s, because I am black, because I have Haitian and Jamaican immigrant ancestry, because I am currently an immigrant, because I am queer, and because my art is the way I have found to express myself about the socio-political issues that affect not only my life, but others’ as well.

Once he defines his theme, based on his perceptions and inspirations — which today draw not only from the plastic-artistic world but also from music and literature — the ideas run onto paper until they become moving images. The great attention that the artist takes when thinking of the documentation of his work and especially the register of his performances, guarantees the conservation of the image as a whole.

Often these objects, used in performances, become sculptural pieces and are exhibited as post-performance objects. “This is another way of documenting the works and for me they are like relics, as each performance I do is unique and unrepeatable”, Martiel expands.

The importance of Carlos Martiel’s work lies in the necessity of everything we are told in Clarice’s work: the recognition of the process of foreignness. The artist goes even further, what is the form of the social portrait we choose to put in art? The birth of a critical stance — of a look not of a utopian society or one that no longer belongs to us but of something with a performative and crystalline look of what surrounds us at this moment, as living and acting beings of a common society.