It’s been 30 years since South Africa entered democracy and legislatively ended the apartheid regime. New language accompanied the entering into this new territory, named the Rainbow Nation. Within it lay multiracial schools, ubuntu, born frees and coconuts that served as a bridge to reconciliation. The last ten years (marked by the Fees Must Fall movement in 2015) unveiled how narrative building overrode what should’ve been nation-building. As the nation we didn’t build reaches its third decade, it invites us to zone in on the material, spiritual and psychological consequences of hosting an undisrupted narrative and what it has silenced.

The Melrose Gallery has met this invitation with a conversation between two curators from different generations and their respective contemporaries. Curator Ruzy Ruzike has titled her exhibition The Agitation to Regain… To Regain, The Regeneration of Africa and cultural worker Sipho Mdada, who lived through the apartheid regime, curated a show titled 30 Years of Wishful Thinking. This conversation is housed by the 2 exhibition spaces that sit across each other in the upmarket high-end fashion precinct called Melrose Arch. Ruzike’s show centres artists making work post-democracy while Mdada echoes in an older generation of voices who made work during and post the apartheid regime.

Walking into 30 years of wishful thinking feels like entering a chamber filled with special secrets. The exhibition fuses painting, sculpture, mixed media and combinations of printmaking. Collectively, they point at the hushed museum of works and artists who’ve been excluded from the canon of art education. They also foreground questions relating to the politics of categorising art practices; who decides what qualifies a work as fine art or craft in the South African art ecosystem? What do these distinctions mean for the work and trajectory of the artists who are placed within each category? Why are these artists grossly undocumented and excluded from the curricula that’s producing the next generation of artists?

In great beauty, the works explore materiality, mysticism, spirituality, fantasy and collective intimacy. Michael Maimane offers oil paintings that provide insight into the intimate space, in The Three Mothers we see three women in communion, preparing vegetables on a wooden table outside what looks like a four-room house, in Jazz he brings a jazz scene that resembles SophiaTown, a black cultural hub where artists and thinkers would gather before it was destroyed under apartheid. Through his command of oil paint, he skillfully renders everyday scenes and landscapes, revealing the essence of ordinary moments from a time gone. Similar to most impressionists, he underscores the ambiance of each scene and affirms the Black intimate space as a site of ebullience and joy. His use of the broken-colour technique accentuates the vibrancy of movement, distinctly capturing the ephemeral.

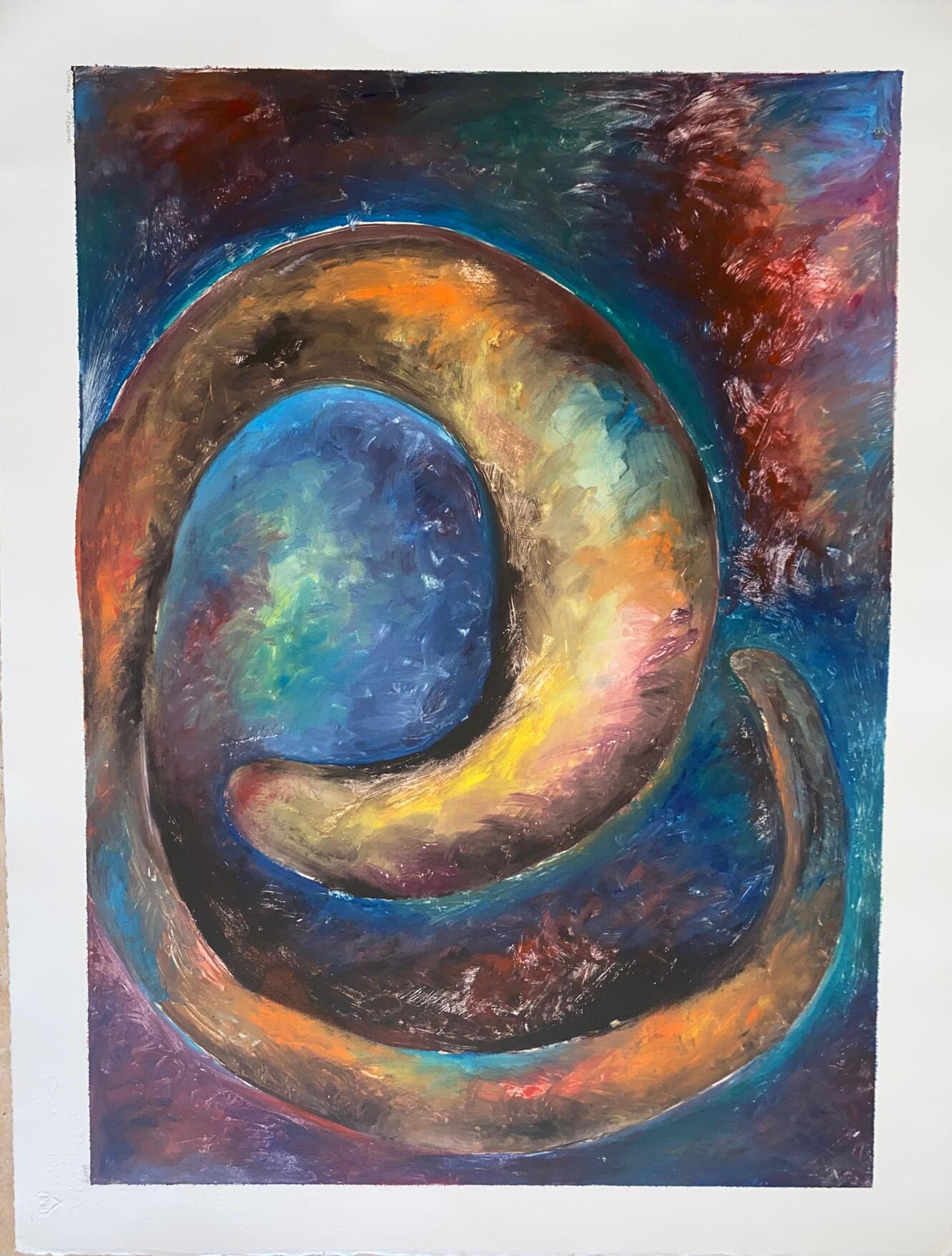

Sarah Tuke’s works create portals into the cosmos, in Beyond The Mind she uses the monoprint technique to create scenes from outer space revealing a vast expanse of stars. Through blending an array of colours, she creates an ethereal glow of distant galaxies and nebulae. Her work highlights an anchoring on nonconceptual ideologies during times of resistance while pointing to the erasure of African astrology and what it means to disconnect space as a repository for insights on scientific, ideological, and spiritual life.

30 years of wishful thinking emphasises communication as one of the main functions of art making. One would expect the tone of this exhibition to be political but abstraction throughlines the approaches to material and forms. Matsemela Nkoana offers large-scale wooden sculptures that serve as semi-abstract portraits depicting African deities and varied forms reflecting his inner and outer reality. When speaking to his sculptural practice Nkoana shares “When I make these holes, I am communicating. I think about the holes in the formation of planet Earth and how they help by bringing energy, in the way black holes do. This informs why I enjoy punching holes, the holes give me perspective then I can see where I am going. As I continue to move through, I’m brought back and controlled by lines that are only perceivable to me.” I’ve observed that bronze and stone sculptures are given great reverence while wood is mostly lensed as craft in the South African context. This leads me to think about the toxins exposed by the wearing off from the rainbow nation narrative against the damage caused by its exclusion of accessible art education institutions such as Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre and Dashiki music and Art Museum. These institutions were independently formed by artists and cultural workers during apartheid with the intention to preserve black consciousness and creativity within art education.

The conversation between these exhibitions implies a responsibility to care through repair onto the younger generation. The Agitation to Regain… To Regain, The Regeneration of Africa Ruzike features painting, sculpture, photography, mixed media and digital paintings from artists who mostly integrated into the ‘legitimised’ art institutions. Ruzike’s curatorial choice centres on figuration to point at the dominant materials, figures and symbols that were present post-democracy. The works touch on state surveillance, a suburban bliss that was accessible to a privileged few, the disappearance of Nelson Mandela and emergence of Winnie Mandela within collective conversation and imagery. She uses the 30-year mark to reflect on the dangers and consequences of inheriting an old consciousness to build a new world while suggesting deep reflection from young artists growing to receive international recognition and acclaim.

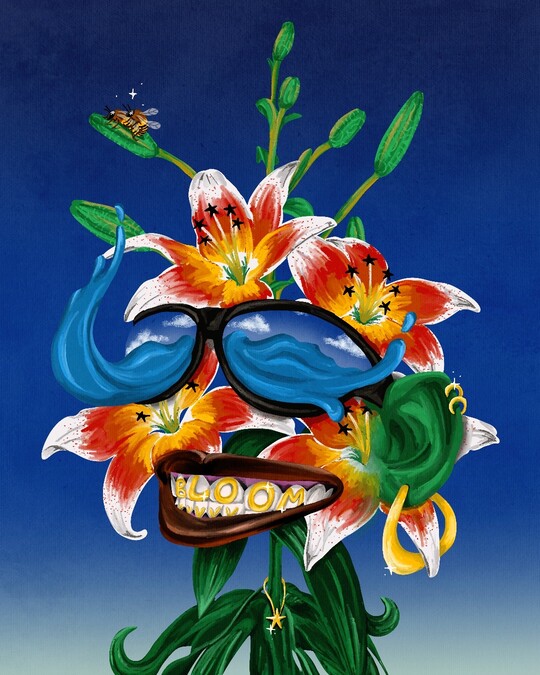

The process of identity mapping throughlines the show, in Sinalo Ngcaba’s Bloomington, she uses digital paint to depict a flower-human in bloom, this green creature is embellished in gold jewels, with grills that glisten ‘bloom’ through a big smile. The painting radiates feelings of joy brought by material gain and self-actualisation. In thinking about self-actualization within an African context, I connect it to Ntu which Dr Nduduzo Makhathini describes as a non-permanent state but ongoing rehearsal that goes through moments of dislocation and fragmentmentation, creating pathways for improvisation to circle back to the paradigm of Ntu. This paradigm also connects to rooting in the indigenous to be fully embodied. Paballo Majela’s sculpture is a totem of the baKwena clan, in Sefata Majoeng we see a black headless crocodile laying on the ground. In this, he foregrounds interconnectedness as an African philosophy, wielding family totems as guides to identity mapping and self-actualisation.

This cross-generational conversation examines the effects of inherited complexities attached to place and time. The colonial severing of generational ties can be linked to the absence of congruence in the dialogue held by these exhibitions. One of the consequences of narrative building was the watering down of ubuntu as a lived philosophy. The agitation to regain beckons a cleansing of consciousness that synthesises a collective responsibility from millennials who eloquently express their interest in engaging processes of decoloniality.

30 years of wishful thinking is a call for care, willing the young to leverage new technologies to restore the archive, take the baton through recording these generators of knowledge and see the present as a time to create new cycles.

The exhibition is on show at the Melrose Gallery until the 25th of August 2024.