It’s important for Black creatives to stay connected, given the surprising similarities in experiences across different parts of the world. I had a candid conversation, with the prolific and accomplished author and artist Kayo Mpoyi, born in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and now a native of Sweden, based in Stockholm. Kayo Mpoyi’s work intertwines history and personal narrative. Our conversation explored themes of heritage, identity, familial history and cultural exploration, and how these inform her creative expression.

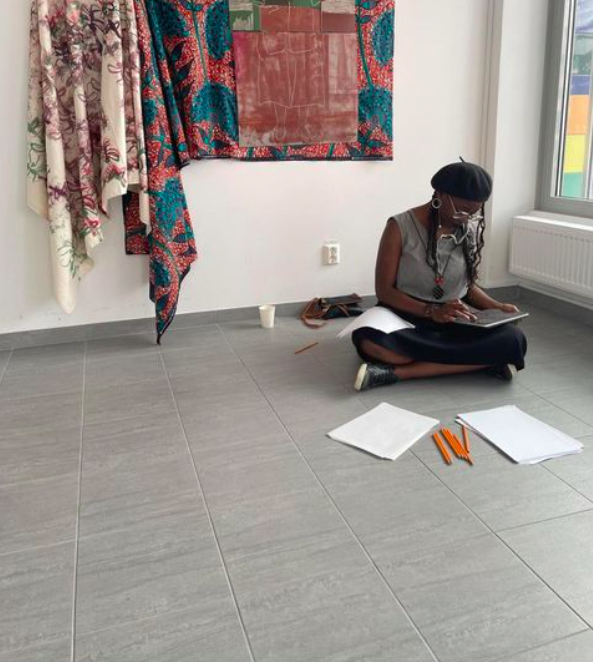

What makes Mpoyi’s story interesting for BubblegumClub is that as a member of the African Diaspora, her story resonates with ours. Born in 1986, in what was then Zaire, Mpoyi spent her early childhood in Tanzania and moved to Sweden with her family at the age of 10. She has studied at the esteemed writer’s school Biskops-Arnö and presently serves as a media producer. I first met Mpoyi at Detroit, an Artist-Run studio space in Stockholm, in 2021, while she was beginning her current studies at The Royal Institute of Art.

Mpoyi’s work mines her family’s archive, but her exploration of her heritage is not without its challenges. Even when I was living in Stockholm, Mpoyi and I would reflect on how alienating Sweden could be as dark-skinned Black Femmes. Growing up in Sweden, Mpoyi still grapples with the Eurocentric gaze that distorts perceptions of Africa and its people. “You live with this double consciousness,” she explains, “where you constantly confront the colonial perspective on yourself.” Amidst the turmoil of cultural dislocation, Mpoyi finds solace in art and writing.

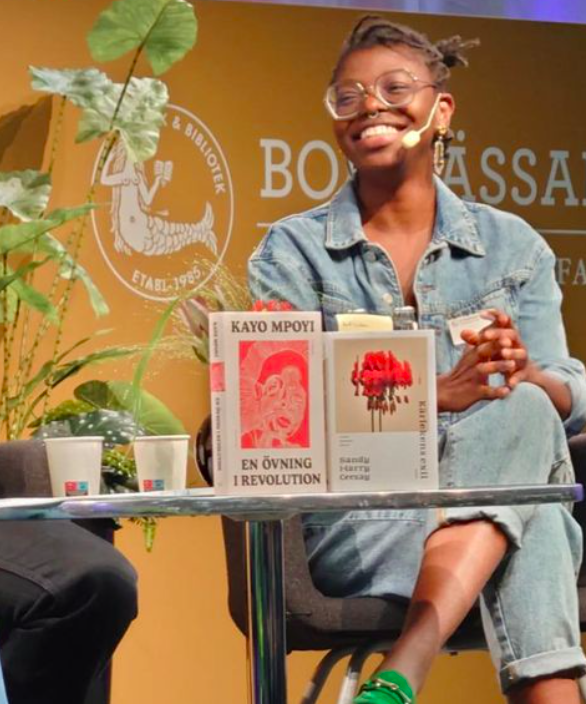

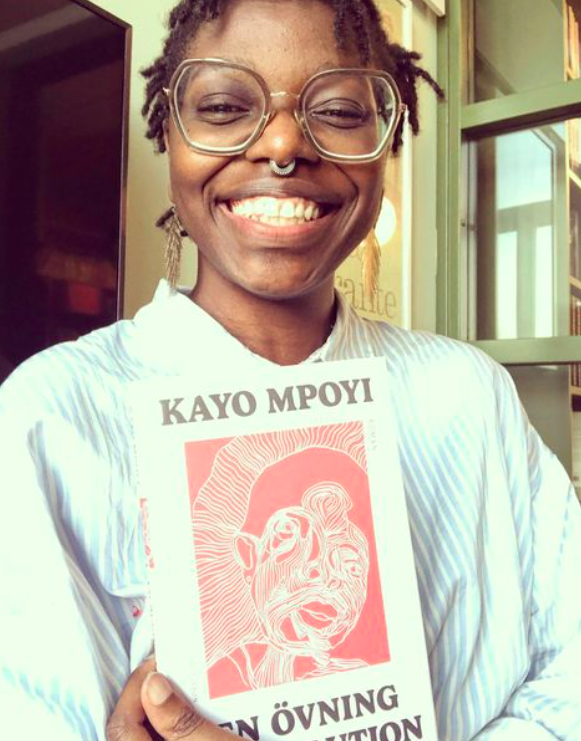

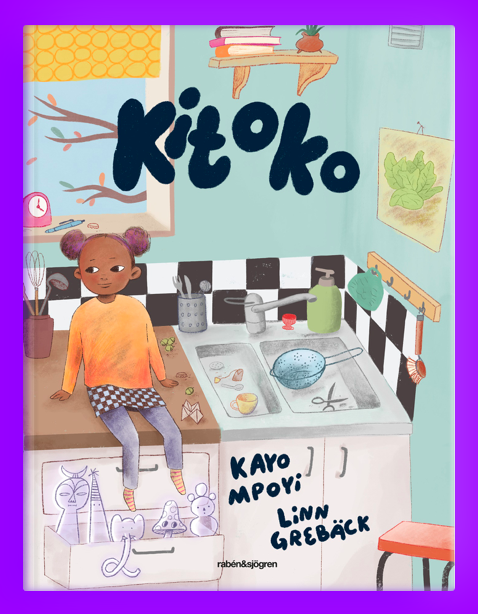

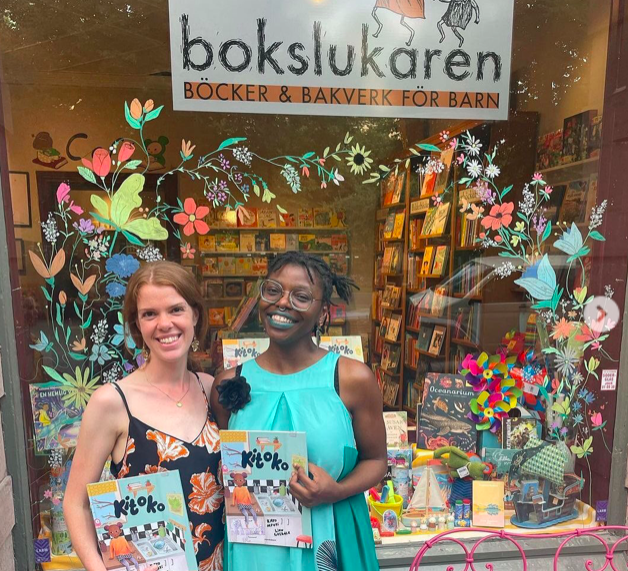

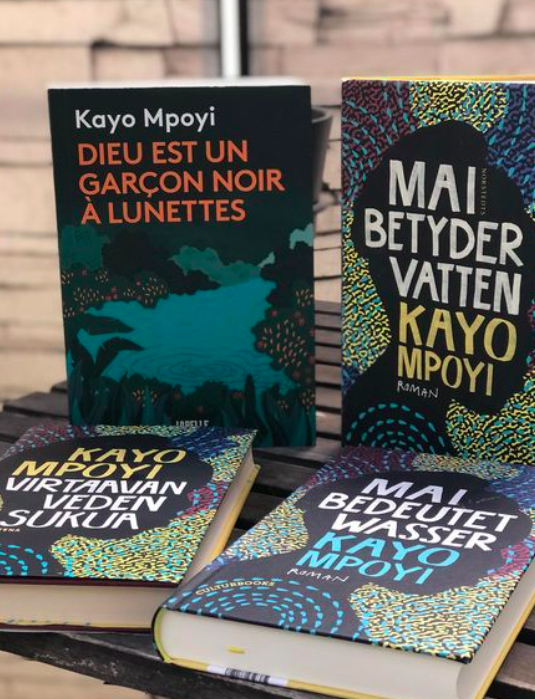

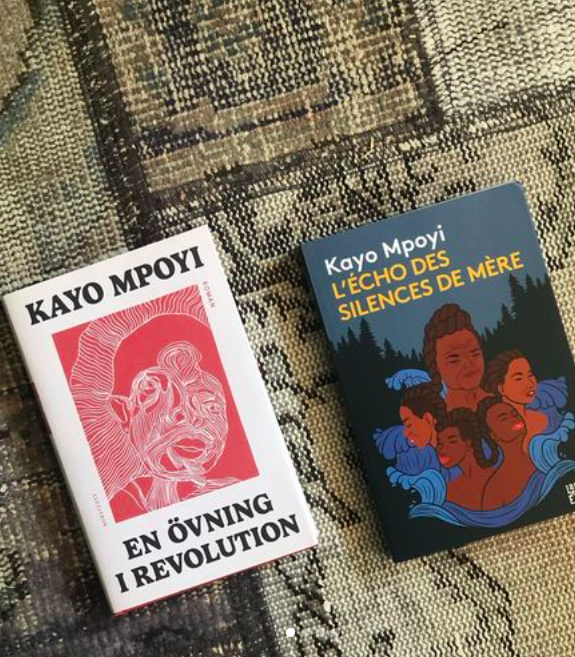

Mpoyi’s novels explore identity, trauma, and intergenerational violence, echoing colonial legacies. Her first novel, Mai Means Water (2020), earned her the prestigious Katapult Prize for best debut. Set in Dar es Salaam, the narrative follows a young girl and explores themes of shame and sisterhood. Kayo Mpoyi’s second novel En övning i revolution (2022) explores family dynamics, focusing on her mother’s struggle in Sweden. In the same year, Mpoyi debuted a children’s book, Kitoko (2022), illustrated by Linn Grebäck.

“I think I’ve understood after finishing my two novels and writing my third, that I’m writing about the same family. Which is sort of like, a copy or a reflection of my own family. … The whole thing is about silence. I think that is the thing that bugs me or bothers me a lot. One is the silence, one is the violence in the family, like, uh, the broken relationships.” In her literary pursuits, Mpoyi also bravely explores the legacy of colonialism and its effects on personal narratives, focusing specifically on themes of silence and violence within familial dynamics.

The integration of her artistic and written work is seamless. Mpoyi incorporates visual material from her family into her artistic practice, drawing inspiration from personal and national archives, including work with the Etnografiska Museet. Having observed many friends and acquaintances in the Diaspora collaborating with guilt-ridden Ethnographic institutions that continue to hold valuable African artefacts hostage, instead of returning them to the African continent, I asked, “The ethnographic museum is a continuation of colonial violence, right?”

“Yeah … But when you grow up in the Diaspora, there is this search for who you are. Because you are a displaced person in a way … so, the search for history is sort of blocked because of trauma. Because the past generation doesn’t speak about history. … a lot of people don’t get the opportunity to go to the museum and see this amazing handiwork. They’re not called art. They’re called … handiwork. … removing the whole artistic aspect, like the thinking and the personality and the individuality of art; the hands that worked with these things. And the thing is, yes, they had a function … A healer going to an artist who would create something. It was a commission. And the healer would use it and … build onto it. And create this medicine.”

So, like many Diasporans, rather than shun these institutions, Mpoyi commends Ethnographic Museums for collaborating with Black curators, artists and scholars and sees this as a path towards challenging dominant narratives and promoting inclusivity in cultural heritage discussions. Mpoyi admits, “ … yeah, that institution is very problematic and the violence that is in that archive is immense,“ but she aims to address historical silences and wounds and to her, the (Black) archive signifies a wellspring of knowledge, healing, and a fresh language for shaping future narratives.

While Africans may call for the return of their own artefacts, a good reason for Diasporans to work with ethnographic museums is that they too wish to engage with these artefacts. During a visit to the Etnografiska Museet, Mpoyi first encountered the intricate craftsmanship of Raffia clothing—a stark contrast to the simplistic stereotypes she had once been fed. This experience encouraged her mission to reclaim narratives sidelined by colonial narratives. “It’s not that the story is forgotten,” she muses, “it’s distorted, manipulated to instil shame.”

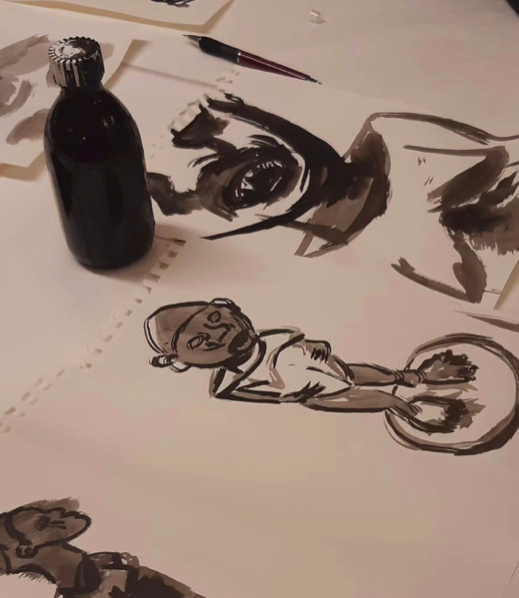

Mpoyi understands the dehumanisation of stolen cultural “artefacts.” For her, these are manifestations of creativity, spirituality, and survival. “They’re not just objects,” she asserts, “but expressions of agency and resistance against colonial violence.” Mpoyi seeks to breathe life into forgotten perspectives through her “story landscapes” and mnemonic devices. “Drawing portraits,” she explains, “is a way of reclaiming our presence, our agency, in a world that seeks to erase us.”

We need more creatives with Mpoyi’s dedication. Looking ahead, she envisions a future where her art becomes a catalyst for social change and collective healing. “I want to create spaces where silenced voices can be heard,” she declares, “where the wounds of history can be acknowledged and transformed.” Mpoyi reflects on a future shaped by the echoes of the past and the promise of redemption. “I don’t know what lies ahead,” she notes, “but I’m committed to telling these stories, to reclaiming our heritage, one brushstroke at a time.”