The persistent impact of colonialism’s “Divide and Conquer” strategy on the relationship between Africa and her Diaspora, necessitates the addressing of entrenched power imbalances and confrontation of shared struggles against economic exploitation and systemic oppression. While acknowledging the historical scars of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade, this article challenges the notion of an overly harmonious relationship, recognising that tensions persist despite longstanding connections predating colonialism.

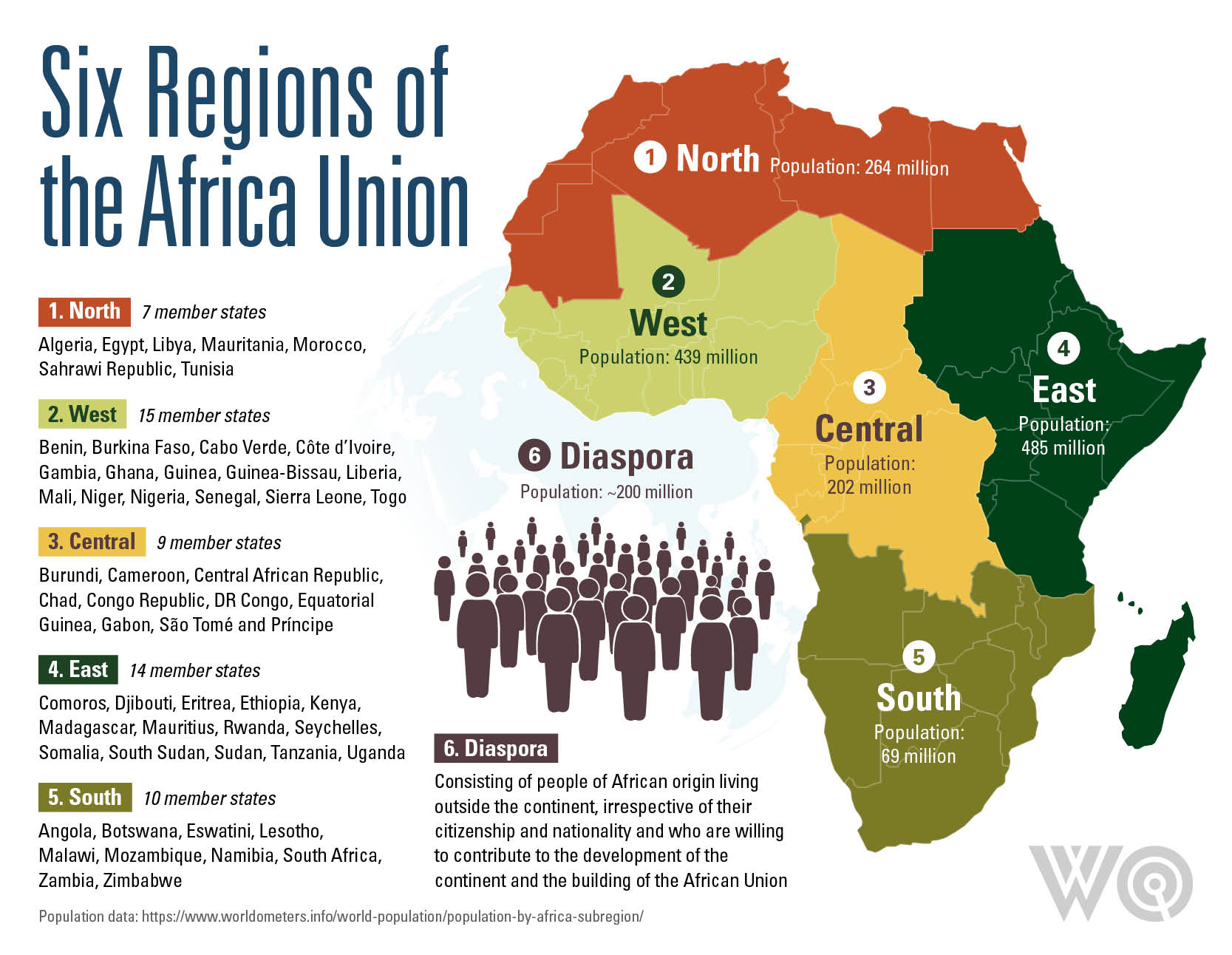

The Africa-Diaspora relationship has deep historical significance, shaping global politics, culture, and economics. It has undoubtedly contributed to Africa’s resistance against oppression and organisations like the African Union (AU) recognise this, dubbing the Diaspora as Africa’s sixth region. Beyond politics, the Diaspora also impacts Africa through remittances, education, entrepreneurship, and cultural exchange. Its importance is increasingly acknowledged, offering new avenues for collaboration and mutual growth.

In her reflections on the African Diaspora’s right of return, Her Royal Majesty Queen Mother Dr Dòwòti Désir called for sustainable dialogue and collaboration among African royal courts, governments, and civil society. She called for revisiting policies on free movement and naturalisation and enhancing government-civil society cooperation to facilitate repatriation. Emphasising collective action, justice, and development, she urged Africans worldwide to unite in shaping their shared destiny.

In the book The Palgrave Handbook of African Women’s Studies (2020), a chapter called African Diaspora and Women’s Struggles in Africa provides an intriguing analysis of the African Diaspora’s role in women’s struggles in Africa, highlighting its connection to broader continental movements for independence and democratisation. The chapter provides examples of how the Diaspora’s impact has been significant, providing crucial knowledge and facilitating economic and social support to empower women in Africa.

While the Diaspora’s sizable middle class is generally seen as an asset for Africa’s progress, the journal article, Africa and the African Diaspora: New Directions of Study (2003) illuminates some of the nuances of how the relationship between Africa and her Diaspora has led to power imbalances. Power dynamics within Africa already vary based on economic development and political stability, and technological advancements enhance connectivity with the Diaspora, meaning the dynamics are never static.

The notion that people of African descent are inherently in cahoots is easy to pull apart. This is a matter of class, not race. The article Rethinking the Pan-African Agenda (2022) critically evaluates Pan-Africanism, initially conceived to combat slavery and colonialism and promote liberation for Africans globally. Its writer Moses Khisa argues that “… the highest point of the liberation agenda, the final defeat of apartheid in South Africa, ironically coincided with the deepening of Africa’s place on the lowest rungs of the global capitalist system …”

In their paper, Reversing brain drain in Africa by engaging the diaspora: contending issues (2012), Idahosa Osaretin and Akpomera Eddy address Africa’s brain drain, referring to the significant loss of skilled professionals due to political and economic factors. In addition to the brain drain, which reinforces Africa’s subjugation, other exploitative extractivist mechanisms can be much more menacing. The latent yet persistent imbalance in political and economic power is part of the hetero-patriarchal system, but it is especially disheartening when it becomes an intrinsic part of the Africa-Diaspora dynamic.

There isn’t even an attempt to conceal the imbalance. A 2020 africanews article highlighted scepticism surrounding Beyoncé‘s adoption of African aesthetics in her Black is King era, with criticism of its monolithic portrayal of Africa. Those unsettled by her capitalist tendencies questioned Beyoncé’s authenticity in interpreting African heritage, adding to existing criticisms of her general commodification of Black feminism and culture. Her recent return to her country music roots employs Americana and patriarchal symbolism, adding complexity to the ongoing debate over frivolous cultural exploitation between Africa and the diaspora.

Beyoncé’s Black Is King (2020) was predated by Solange’s Losing You (2012), and countless other voyeuristic portrayals of African culture from a Diaspora lens. African Americans, though often illustrative of this inequality, aren’t its sole embodiment. With over 170 million individuals worldwide, the African Diaspora is vast and plays a ravelled role in Africa’s development, with many returning to invest in its economy. Unfortunately, even with noble intentions, engagements with Africa are marred by hierarchical systems, often relegating Africans to the background, seemingly less worthy than those who engage with them.

Far from hopelessness though, there are ample initiatives that seek to rectify the power imbalance between Africa and her Diaspora. In a paper called,Africa’s democratic deficit: The role of the diaspora in bridging the gap between citizens and government (2019), Tutlam et al. examine the Diaspora’s historical influence on Africa’s socio-political landscape, advocating for a collaborative approach to address political participation limitations, drawing on experiences from countries like The Gambia, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe.

The African Charter intends to rectify power imbalances in global African scientific knowledge production by addressing colonial legacies and Western-centric viewpoints that hinder African scholars. Earlier this year, Dann Okoth explored these issues with Professor Isabella Aboderin, the director of the Perivoli Africa Research Centre (PARC), originators of the Charter. In a 2023 blog post, Susan Jim and Caroline McKinnon from the University of Bristol discussed power dynamics in research collaborations between the Global North and Africa.

Such initiatives are advancing innovative strategies to tackle funding disparities and bolster Africa’s global academic standing. However, more collaboration is required across economic, cultural, political, and social sectors, involving governments, civil society, academia, and grassroots movements. Technology and globalisation further facilitate collaboration with Diaspora organisations. Achieving shared goals of prosperity, dignity, and self-determination for all individuals of African heritage worldwide should be more feasible now than ever before.