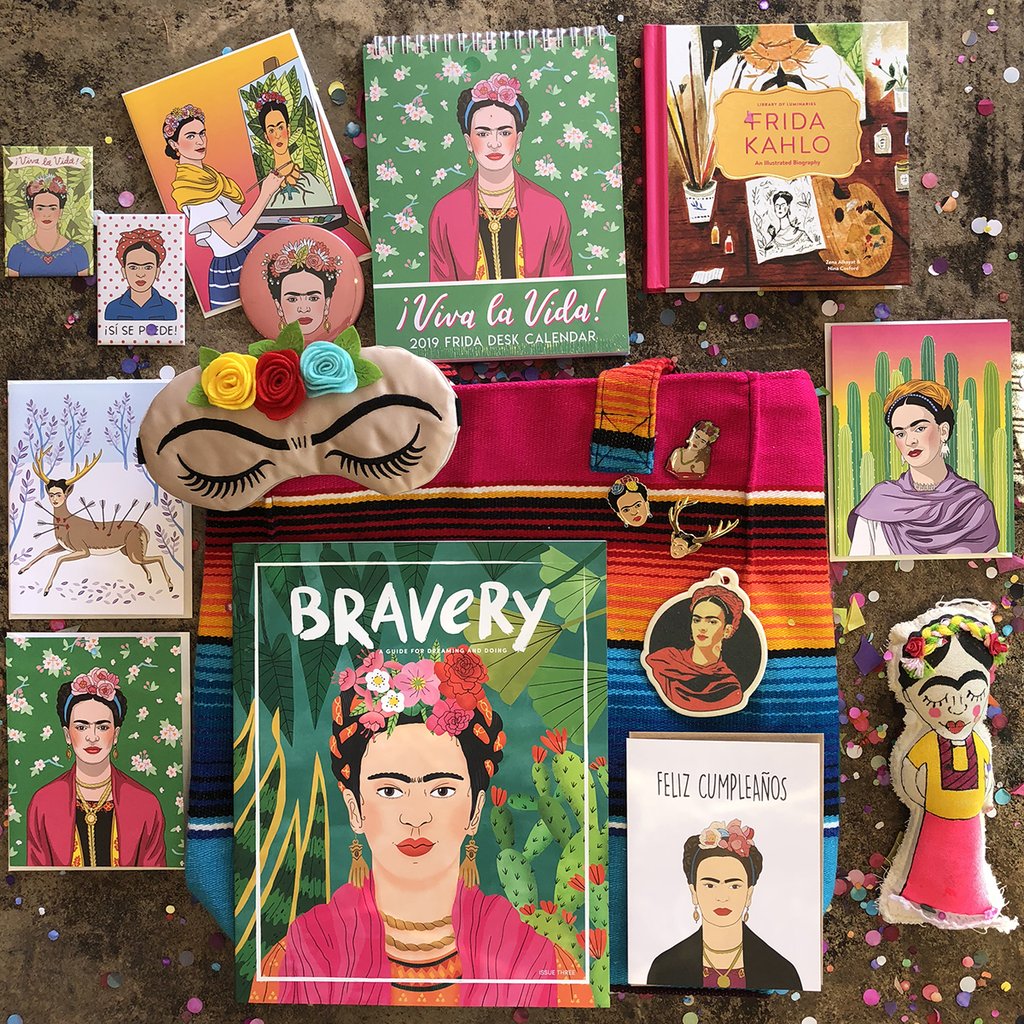

Yesterday marked what would have been Frida Kahlo’s 114th birthday and in a celebration of the fact, Dazed posted an Instagram graphic reminding people of a piece they published in 2018. The piece titled “Frida Kahlo is not your symbol” by writer Ayoola Solarin appeared to me at a time in which I had already been questioning artists and artworks as symbols within popular culture. The title of the Dazed piece was derived from a poem by Oroma Elewa, usually misattributed to the artist Kahlo. In the piece Solarin explains how Frida Khalo was turned into a symbol following her passing, a symbol made palatable to the general public and made to represent the “girl boss” thinking that surrounds white feminism. In truth, Kahlo was turned into a symbol that stood for the very things that she was against, in a manner that falls into the foundations of capitalism; merchandising her image and appropriating it to be mass produced and therefore mass consumed. As Kahlo was a communist and created works surrounding this, her commodification and icon status in popular culture shows how much meaning is lost through iconography in this way. Kahlo, like many other artists before and after her, had fallen subject to popular culture’s “borrowing” of symbols for aesthetic value. Symbols such as Kahlo’s portrait are reproduced and placed on merchandise constantly, removing them from the frameworks they once existed in and the concepts they stand for. Through every reproduction, the meaning of these symbols steers further away from the meaning the artist created them to convey.

Image sourced from internet archives

The age old saying “art is in the eye of the beholder” rings truer when we think about how art has now come to exist outside of its usual paradigms and entered popular culture as symbols or iconographies, each barring different meanings in contrast to their positionality in an art history context. Due to their popularisation as merchandise, the works of Kahlo, Haring or Banksy are sooner recognised as “cool” posters and T-shirts than they are as conceptual works of art. This allows for people to first become familiar with the works as symbols in the context of popular culture based on their aesthetic value alone, disregarding the deeper meanings they represent. As an artist who has come to know the artworks from an art history point of view, it becomes frustrating to me when artworks are appropriated by popular culture and paired with watered down meanings. However, this frustration was almost questioned when I began to study the works and mode of operation created by Takashi Murakami. Murakami presented to me a conceptual framework that almost pre-empted the fate of his artworks being used as symbols in popular culture by blurring the lines between high art and pop culture, in doing so allowing art to be accessible and still retain meaning.

Murakami’s Neo-Pop mocks the post-war Japanese consumer culture by “sampling” and “remixing” its themes and characters in high art. Through his work, Murakami critiques Japan’s contemporary culture and also popular culture’s intruding influence on art, and visa versa. Murakami’s vibrant flowers, and other characters, are an example of a symbolism that begins to appear in popular art in a way that is distanced from their intended meaning in the world of high art. Yet, these symbols begin to create their own visual language in the pop culture space that still aligns with Murakami’s conceptual framework. Murakami merges Japanese pop culture with the country’s artistic legacy, creating work that pushes the boundaries between commodity and high art. His art is influenced by the otaku subculture in Japan, which is filled with perversions of cuteness and innocence, as well as shocking brutality.

While Murakami’s flowers are often subject to interpretations based only on their aesthetic quality – an interpretation which I would usually deny thinking that it robs the work of its intention – it is clear that Murakami, through the mass production of his work as well as creating works ranging from high art pieces to toys, has allowed his work to exist in multiple paradigms without it being appropriated. I say this with the thinking surrounding Murakami’s work itself as framed in the idea of the artist imposing Japanese culture onto the west, specifically America, in retaliation of the histories between the two countries and Murakami’s belief that the fixation with cuteness, youthful innocence and violence is the result of the American involvement in Japan. There is no better way to impose one’s work onto America than to make it easily consumable and ready to be appropriated and mass-produced. Through this, Murakami critiques the very point I am trying to question surrounding art’s lost meaning in popular culture by presenting a way of working which disrupts the way we appreciate art across discourses. Murakami creates work that everyone can enjoy, that is almost ready to exist in every sphere, whether as conceptual pieces or based on aesthetic value alone. Even when appreciating the work on aesthetic value alone, consumers of Murakami’s work play into the conceptual ideas which underpin it – the need to impose his work into western culture and accessibly to art as well.