On the 1st of August, the Wits Art Museum opened a solo show by Swiss/Italian artist Nicola Genovese. The exhibition titled, Sad Boy explores masculinity and the decay thereof. The day before the opening, I had the chance to interview Genovese and gain insights into his artistic intentions and material choices. The artist contemplated the term “queer art” and the inherent queerness of art, suggesting “queering the material” as an evocation of both the fragility and threat of his show.

The well-attended opening of Sad Boy was quite an event. The Wits art department (and other Joburg art world) cohort were in ample attendance, and it must be noted that they too are mostly white and masculine identifying. Robin DiAngelo coined the term “white fragility” in her book White Fragility (2020) exploring white people’s defensive reactions to racism, attributing it to largely segregated societies that shield them from racial discomfort. The South African art world is a perfect example. To this extent, it makes sense that they identify with Genovese’s work, which Christo Doherty, one of the supervisors of the artist’s PhD was all too proud to point out in his opening talk.

But this particular flavour of white pride was somewhat softened by an inevitable presence of Black folk who came alive during Genovese’s opening night performance, in which he reflected on societal expectations that led to feelings of inadequacy. He shared Italian working-class anecdotes of men whose pride lay in their defence against emasculation and touched on masculinity’s biological complexities, admitting to using Viagra to regain self-confidence. Aware it may be labelled as “white fragility” or “white male privilege,” Genovese remains unapologetic, announcing this will be his last explicit performance on the topic as his artworks will communicate his message going forward.

The Day I Got Stuck In Your Garden; 2023; HD video loop, 5 minutes

Beyond the dazzling opening and thrilling performance, the art surely does speak for itself. At the physical and conceptual heart of the exhibition is a video titled The Day I Got Stuck In Your Garden — the first work Genovese chose to share with me on our walkabout. Featuring an anti-heroic, almost pathetic avatar, 3D modelled after the artist, it is dressed in Baroque clothing and writhing in repetitious pain. Humorously receiving constant smartphone notifications, Genovese’s bleeding avatar is trapped in an endless loop, akin to non-player video game characters who are ironically seemingly impervious to pain.

Genovese’s version of Venice (the setting) further adds to the video’s surreal quality. The images are made on Midjourney, juxtaposing the city’s historical significance and its tourist fascination. Skillfully intertwining elements from the Venetian Renaissance with a dystopian future, The Day I Got Stuck In Your Garden comically prompts viewers to question their digital-era perceptions.

Sad Boy; 2023; Quilted Textile; 240x120cm each (x3)

The headliner of the exhibition, Sad Boy, commands the most wall space in the gallery. Created in collaboration with an unnamed Braamfontein tailor, it comprises six large metallic-looking textiles forming the letters ‘SAD BOY’ in an oddly contemporaneous yet gothic lettering style reminiscent of the Y2K era that is currently making a resurgence. Upon closer inspection, the polyester pieces begin to resemble blankets, evoking familiar synthetic materials found in pillows and duvets.

This juxtaposition of the garishly metallic surfaces and the plush softness behind them results in an intriguing interplay between femininity and masculinity. As Genovese’s exploration of ‘Sad Boy’ aesthetics aims to use vulnerability to challenge traditional notions of masculinity that have historically been detrimental to men’s well-being, this work is something of a triumph.

Cramps is the first work one sees when walking into the exhibition space. Made from various metals and faux leather, this piece is reminiscent of medieval armour, underscoring the idea of vulnerability and protection intertwined. Its worm-like quality and odd phallic bits leave very little to the imagination.

Cramps (detail); 2023; Metal, resin, fake leather, copper; variable dimensions

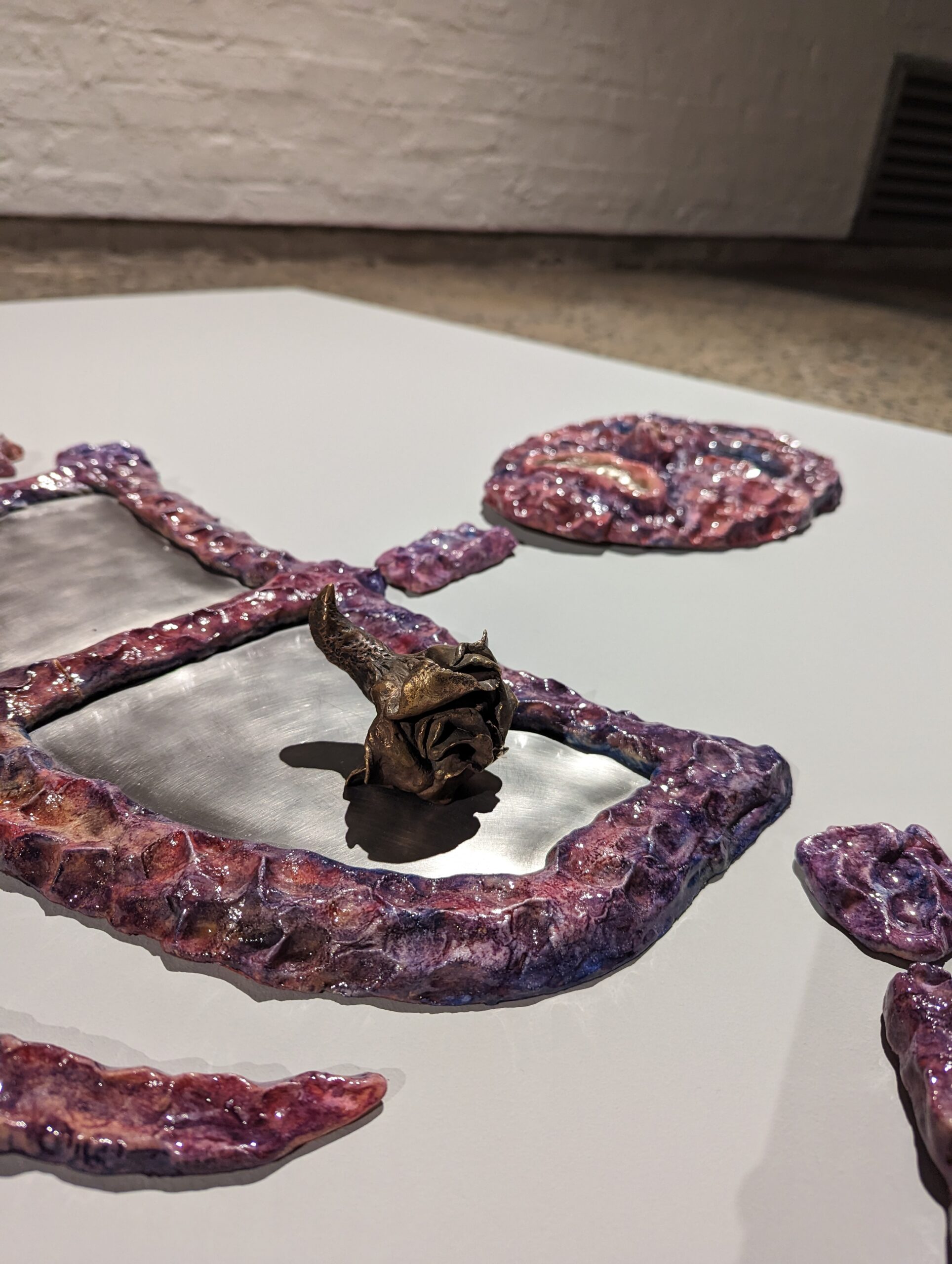

In My Prime; 2023; Salt dough, watercolour, metal, bronze, textile, resin; 340x180x35cm

Depicting a seemingly silly skeleton, In My Prime further experiments with charmingly petty materials, presenting them in a wryly opulent manner. Questioning the divide between high and low art, the sculptural object is made from resin, gold leaf and a delicate bronze piece. When I asked about this use of materials, the artist promptly picked up a piece and let me hold it. It felt smooth to the touch and it was light, contrasting the facade of hard heaviness it evoked while laid on the floor.

It’s impossible not to identify elements of kitsch in this piece and the exhibition as a whole. I even go so far as asking the artist whether Memento mori, the Italian art genre that emerged in the middle ages plays a part, to which the artist generously responded: “I’m 51 … I’m not young anymore and I’m realising death is a big taboo … I think it’s the last taboo, especially in Western countries … and my mother died recently of Alzheimer’s disease. And uh, it’s funny because when she died, I was making this work. It was serendipitous, you know?”

In My Prime (detail); 2023; Salt dough, watercolour, metal, bronze, textile, resin; 340x180x35cm

While I have a dangerous obsession with this subject matter, I did not wish to impose on the artist’s grief, so I swifly moved on, asking Genovese what place this exhibition has in an already fraught and fickle context like Johannesburg. Acknowledging class, history and privilege, his answers were satisfactory, but I made my own inferences, drawing comparisons between contemporary Italian and South African art.

Arte Povera and so-called ‘Township Art’ are two distinct Avant-Garde movements with different origins, themes, techniques and social implications, but upon walking into this exhibition, the comparisons were clear. Arte Povera emerged in Italy during the late 1960s, exploring themes of social justice and working-class identities in response to economic changes and the Americanisation of Italy. The movement’s name is translated as ‘poor art’ and it challenged traditional art values by using everyday materials.

Township Art was born during apartheid South Africa, and it also used accessible mediums to depict daily life and political struggles. This tradition has clearly influenced contemporary South African artists like Bronwyn Katz, Bonolo Kavula and Lungiswa Gqunta, as well as artists across the continent like El Anatsui, challenging conventional art notions with the impactful use of “cheap materials.” Of course, the pertinent question here is the notion of materiality.

Genovese admits that as a Swiss/Italian artist, he has privileged access to funding and materials, but maintains a preference for “cheap materials” like textiles. He finds inspiration from feminist artists like Leonor Fini, whose soft sculptures portrayed fragments of the body, and Louise Bourgeois, whose art similarly explored representations of the body through textiles.

Though I boldly and repeatedly made the comparison to Arte Povera and Memento mori, Genovese did not quite agree, and I respect that. For him, his artworks are more of a reclamation of the grotesque—an aesthetic often associated with kitchness and other Northern European traditions. The grotesque embraces exaggeration and embellishment, a characteristic intrinsic to Italian Baroque art. For Genovese, the grotesque becomes an act of resistance against the prevailing minimalist trends that have pervaded the art world, particularly in Protestant-influenced countries like South Africa.

Genovese’s work subtly evokes monstrous features like mangled digits, open wounds, flaccid penises, oozing faeces and decayed corpses. Using accessible materials, gothic lettering and obscure elements from art history, Genovese’s Sad Boy challenges traditional notions of masculinity, rather embracing fragility and inviting a soft contemplation of the grotesque and the sublime. The exhibition runs from the 1st of August and the museum hours are Tuesday to Saturday from 10 am to 4 pm.

This story is produced in the context of an editorial residency supported by Pro Helvetia Johannesburg, the Swiss Arts Council.