The Natural Nancy Doll was supposed to help soothe some of the tension that lay lingering after the riots had quieted down. After the Watts Rebellion of 1965, the city of Los Angeles was in critical need of a social rebrand. Decades of racialised inequality and a matchstick incident of police brutality against Marquette Fry (on the hook for driving while Black) culminated in six days of civil unrest and rioting all-over South-Central LA. Black civil rights activists from Operation Bootstrap Inc, a Black Power economic self-sufficiency programme, met with Mattel (the company that makes barbies) to talk through what would become a radical product. An agreement was made that Mattel would provide capital for the creation of Shindana Toys; the first Black-owned-Black-made-Black-marketed doll company. Shindana’s main factory took up roots in South Central, employing Black factory workers and enlisting Black toy designers to create a selection of dolls that reflected the community.

The Natural Nancy was a dark chocolate baby doll, with a short afro, full lips and a wider set nose than any other doll on the market. They had other dolls on sale too- like Wanda the Sky Diver -created to give people something that represented them in roles that were both accessible and aspirational. Dolls like those the Shindana Company were making are a foundational part of growing up Black; each doll functioning as a memory of the times in which people have found themselves.

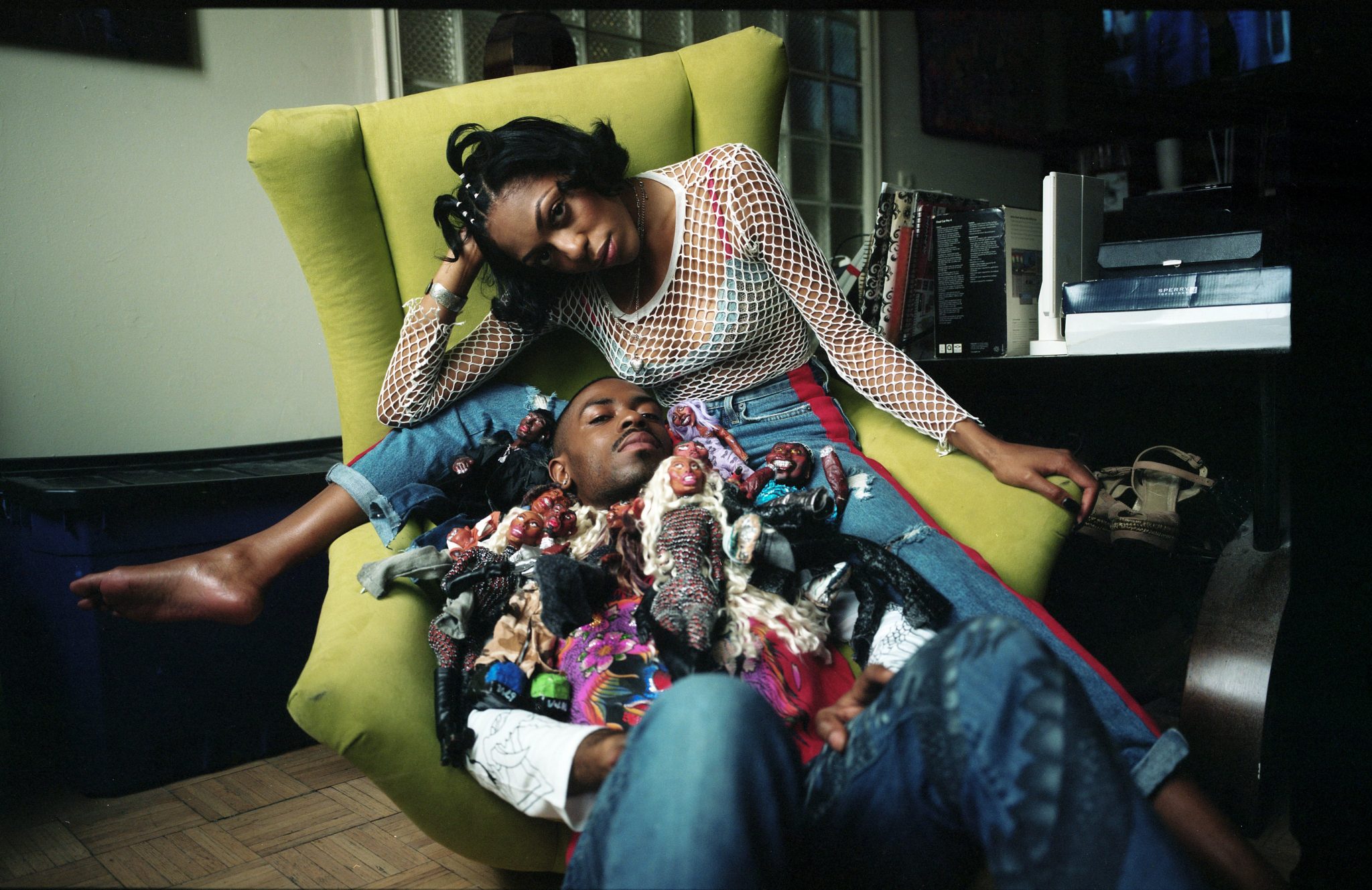

Photograph by Dare Dollz

Conversations about Black dolls didn’t start or end in Watts. The doll has taken different forms across the Black world. Carved wooden figures coming out of Africa, like the ‘colonial men’ figurines and ornate Ashanti carvings, have been placed in both the Africa sections of museums and on mantle places in Black homes across the diaspora. In the US, the doll has a long and intimate history and connectedness to community representation. The Topsy Turvey doll, a bi-racial two-bodied cloth-doll popular during slavery, helped usher Black dolls into the market for the first time. Designed with the politics of the civil rights movement, the Natural Nancy helped popularise a doll that had ‘ethnically correct features’, de-popularising the brown-tinted euro-dolls that Black children had been using for decades. With this new babydoll, children got an image of Black dolls that reflected their childhoods more honestly than ever before.

From her came Christie. Barbie’s first black friend was born in 1965. She had a blunt-cut with grey-brown hair. Rouged cheeks and pink lips, her makeup and hair both an evident sign of the times. The Christie doll helped officially usher in a wave of Black dolls of all varieties on the market. African-inspired babydolls wearing dashiki prints became more widely accessible. As Mattel recognised a growing trend in black purchase, it expanded its range to create more versions of ‘Barbies black friend’, offering different hairstyles and clothing options for the original Christie doll. Barbies black friend laid a sort of skeleton for artists to develop the dolls themselves. I’ve seen Barbie’s old-sidekick transformed and beautified according to standards of beauty that reflect the way Black beauty standards have developed over the decades (see the Alma Negra). Through the Black doll, intimate connections have been drawn between and across the diaspora; connecting small wooden and plastic hands together in Black experiences.

Photograph by Dare Dollz

In hip-hop, Black dolls have had an almost permanent role in shaping aesthetic culture. In the 90s, the puppet became a popular trope in music videos, standing in for the musicians themselves. Though not dolls in their most traditional sense, the puppets took on the characteristics of the era much like a doll would have. Music videos like Blackstreet’s “No Diggity” and Eminem’s “Ass Like That” both feature puppets playing people and sound tracked by some of hip-hop’s biggest songs. As Mattel expanded, so did its budget for creating celebrity inspired dolls. A couple of them, over the years, have been Black. A blonde Beyonce, a faux-loc era Zendaya and a feathery haired Diana Ross have all been immortalised through the Barbie. Most notably, the desire to be doll-perfect has come out in the music.

Nicki Minaj’s ‘Black-Barbie’ persona has become a staple that travelled with her, even after the iconic Pink Print era. Her own doll has a blunt cut, candy-floss pink wig on with a diamond nameplate ‘Barbie’ chain. In hip hop and within wider Black culture, the doll has continuously been a symbol of perfection that can be manipulated according to the prevailing Black standards of beauty as defined by that moment of temporality. “In Black art, I think Black dolls are looked at as rare collectibles”, artist Darius Moreno says. “In hip hop, I think dolls are kind of associated with dark themes versus lighter, happier themes. I can appreciate both because most Black dolls come from a dark, long history from specific cultures. I do wish that hip-hop themed dolls were more accessible, though” he continues. “Especially for kids who feel like they can’t play with dolls growing up”.

Photograph by Dare Dollz

Darius and Dare Moreno created Dare Dollz, a universe of urban-glamour clay dolls, in 2018. “We were in Virginia Beach at our grandparents house, just thinking of things to create” Darius tells me over email. “My grandmother has a room dedicated to her doll collection. After really studying that room, we realised the importance of dolls for every age group. We knew that we wanted to make our own and did that within a month of us staying there.” Raised in the DMV (the area stretching between D.C, Maryland and Virginia), the brother-sister duo started making dolls inspired by almost everything. “The facial and body structures are inspired by some ballroom icons that I love” Darius explains. “I love androgyny and how a person’s confidence can be shown just through physical alterations because of the boldness of it all. When it comes to clothes, we draw inspiration from our family members, who’ve always been very stylish for generations. We also really love Japanese culture, the detail they put in all of their art is an inspiration”.

The Dare Dollz exist in a claymation universe that is opulently Black. The female dolls have neon inches, coiffed into perfect updo’s. They have long acrylic sets and razor-sharp winged eyeliner. One doll wears a thick purple teddy fur coat with a yellow and black minidress. Another wears fishnet stockings and a snakeskin leather jacket with purple fur on the trim. The male dolls are equally done up, with their hair laid into perfect waves and diamond jewels on each earlobe. The dolls exude the type of glamour that defined the late-80’s and early-90s; confident, bold and articulating the definition(s) of ‘urban’ for themselves, outside of whatever connotations not located within their universe(s).

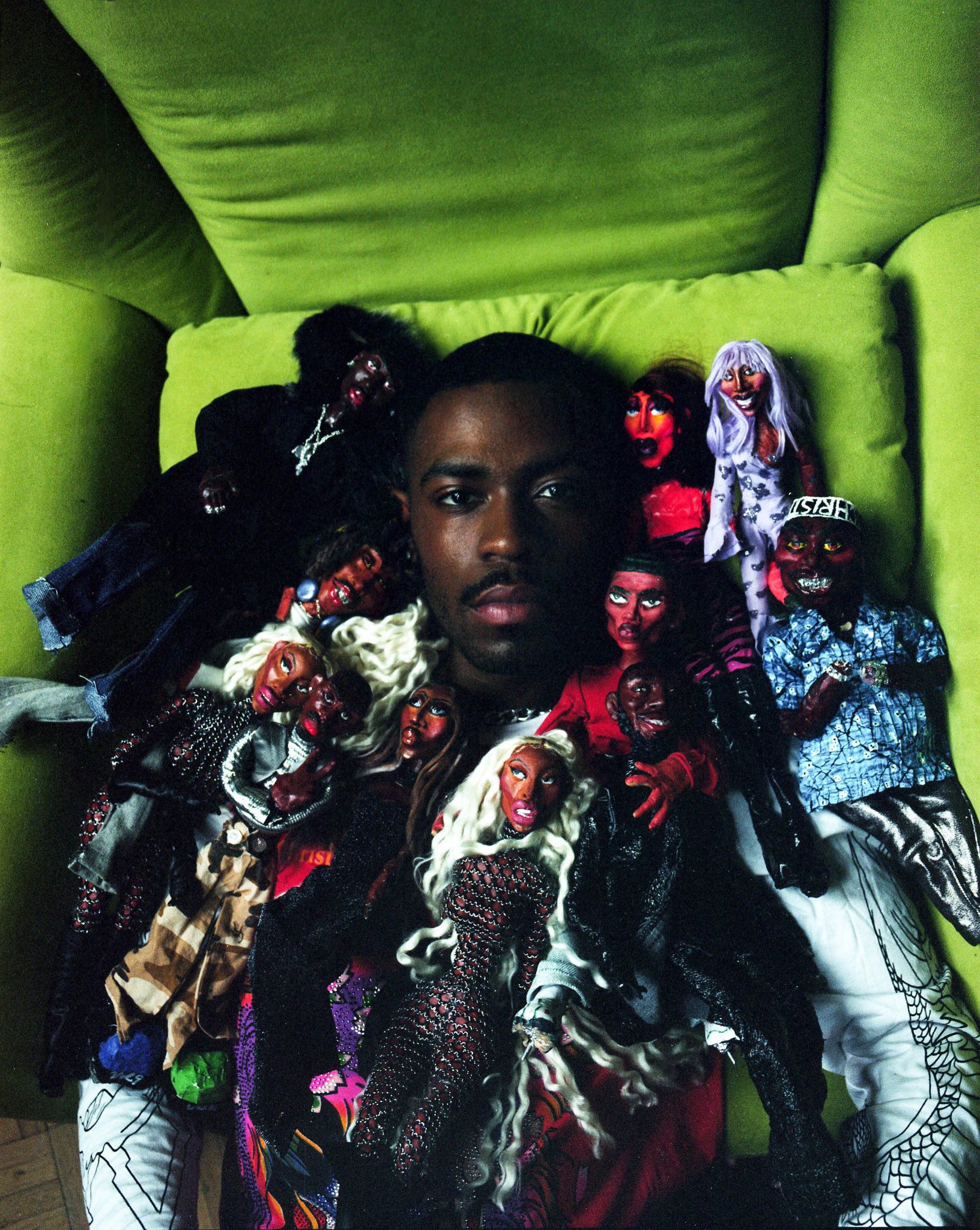

Photograph by Jeremy Grier

Life is represented through the Dare Dollz themselves. Aside from the outfits, the facial and physical compositions of each doll is its own narrative. Each doll is inspired by people the artists know, sometimes a combination of individuals. Sitting, slouched, eye’s low, clutching a titty, blowing smoke. The Dollz appear each with a unique personality and story, representing the different moods and intersections. “Everyone wants to see themselves in a doll, whether they admit it or not” Darius says. “As a child, a doll is like a foreshadow of who you want to be. [There’s] always been a lack of diversity in dolls and when they make them diverse, they come out looking goofy. We want to show that you can be beautiful and confident no matter what you look like through our dolls”.

Creating dolls made for a Black, adult market is an interesting space to find oneself in. In the same way that dolls geared towards children have served as an introductory form of representation, dolls geared towards adults open up conversations for how we see people and how we want to be seen. “We want to be as authentic as possible” Darius and Dare tell me. “So, dealing with adult themes helps with that. Even if that means some dolls aren’t always in the best moods or doing the most logical thing. Our dolls make mistakes just like adults do. We want to show that they can learn from them too.”

Photograph by Jeremy Grier

While dolls aren’t a dominating aesthetic right now, the Moreno’s have a distinct visual imprint that’s impossible to ignore. The personality that jumps off the clay, rich colours, dark brown hues and deep, dramatic facial contours make the figures unique to the Dare Dollz universe and hard to ignore where they do pop up. The Dollz have appeared in the cover art for musicians like Goldlink (also from the DMV), Bucky Malone and the O.G Invictus. Darius also led the creative direction on the cover for Goldlinks At What Cost. Although it exists as an illustration, that cover is almost unforgettable, and its rich quality makes the Dare Dollz look so unique.

In the space that exists between history and culture, the Black doll has stood the test of time as a tool of representation and self-actualisation. Where dolls were made without Black people in mind, aesthetics have been manipulated and shifted to create something new. Like so much of Black culture, the doll has reformulated and evolved as to give rise to something that is so unique and separate from its Western origins thus in a way doing the working of denouncing them. Through the doll itself, a kind of counterculture has developed that challenges ideas about Black aesthetics, modernity and beauty. The Dare Dollz, specifically, are created in the image of people, places and scenarios that would never be put into a factory or a shiny pink box. “Dare Dollz aren’t just dolls” Darius explains. “They aren’t just toys, but they can be used as a reminder of how you should view yourself. That doesn’t mean I want people to look exactly like the doll, [just that] our dolls embody style, confidence and pride in whatever it is you’re trying to achieve”.