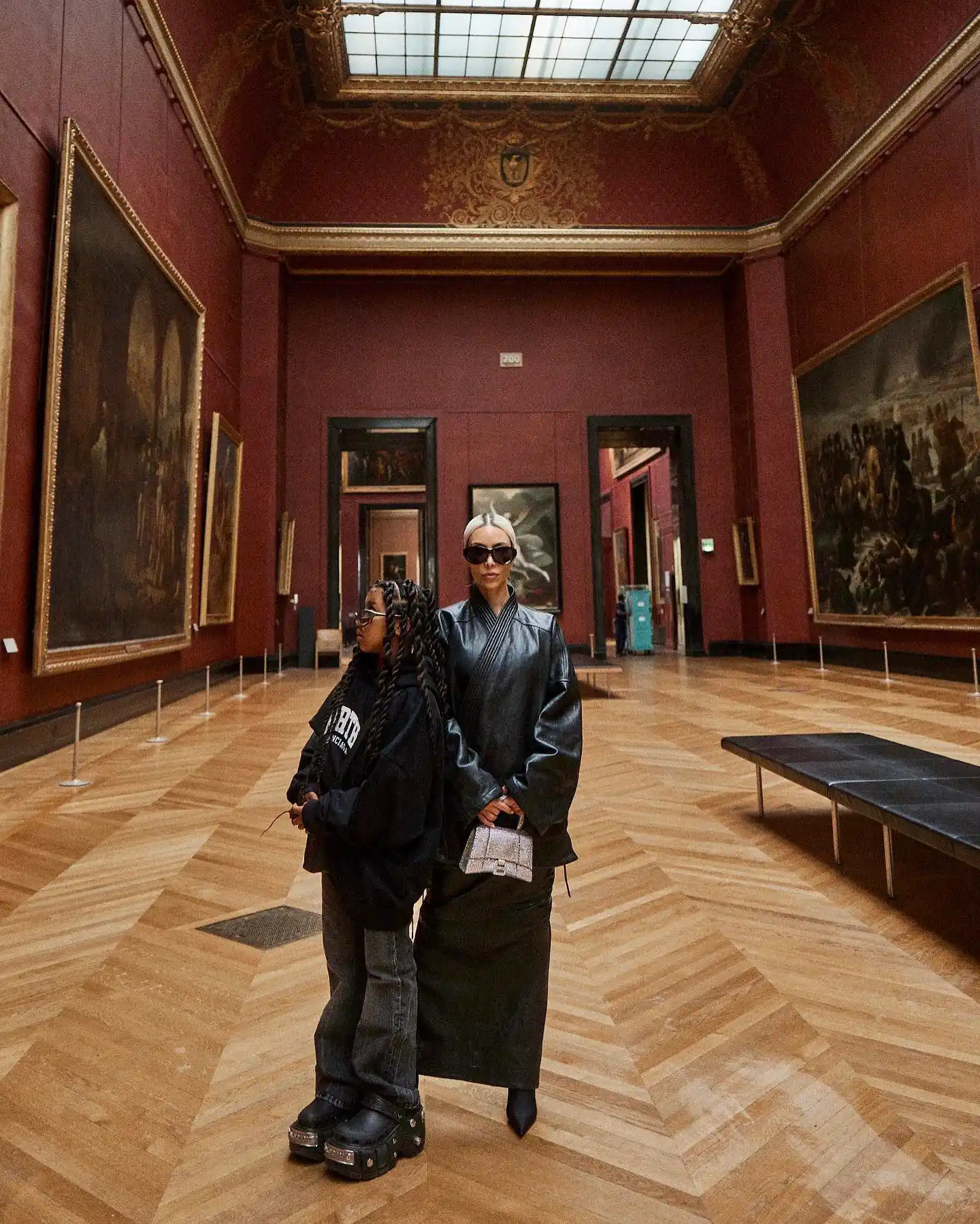

It’s a thing, we’ve all done it or seen it before. We turn our backs to the camera as we glean meaningfully into the art on the walls of galleries. It’s like a gaze upon a gaze. Or, we turn our backs entirely, allowing sizable artworks to be our backgrounds, embracing us almost.

Why do we do it?

In the moment we capture a photo of ourselves posing in front of artwork; we have captured a dialogue of aesthetics. We present ourselves before art, which presents itself back to us. The dialogue between fashion and art in particular is a long standing one.

Haute Couture dates back to Paris in the 19th century. By all means, the parallels are right there between Haute Couture and traditional fine art: a creative mind conceives an idea, perhaps sketches it first before bringing it to life, and signing a signature (or stitching it into the garment). And much like the most prized of fine art possessions, the idea behind Haute Couture is that it is an original, made very specifically for clients and not mass produced.

The relationship has only seen continual growth and strengthening, with technology allowing both industries to innovate more in terms of the power of prints and screening. Right here at home, the latest Adidas x Thebe Magugu collection features the collaborative work of artist Phatu Nembiliwi. Indeed, the relationship between art and fashion is stronger than ever.

However, it doesn’t directly answer the question of why we pose in front of art.

The answer lies in the same place that questions why architecture has a focus on aesthetics at all. A building, be it pleasing to the eye or not, would be able to stand, house and shield all the same. But we are humans. We don’t live like machines, created for functionality. We need things to be beautiful. Research within neuroaesthetics – a field which focuses on the effect of beauty on the brain – shows that beautiful spaces improve our psychological and emotional wellbeing. Beautiful spaces possess a kind of soft, but important power.

And in some of the most densely populated places in South Africa, like central Johannesburg and parts of Cape Town, the space is still charged with the Apartheid government’s affinity toward brutalism architecture. While some celebrate the functionality and simplistic but strong design of these buildings, none of their focus is on beauty. In the hustle and bustle of these busy metropolitans, the tall brutalist buildings tower above citizens performing the same song of function. So, in these very same cities, which also serve as major arts and creative hubs, finding the galleries is like finding a little pocket of humanity. A reminder of the deeper need to be in a space which feels welcoming and reflects the need for beauty, and not just necessity.

That’s what art does: it reminds. It was the call of famed visual artist Esther Mahlangu that we never forget our cultural roots. Her famed work is the painting of traditional Ndebele decorative elements, which would be painted on houses and updated to mark moments of importance to the community. It is a reminder that there was a time, as Africans, that we didn’t have to find little pockets of humanity within the galleries and white cubes. They were on the walls, all around us, on display. It is the recognition that beautiful spaces are a need, and are functional. Their function is to anchor us in something humane.

So when we see people entering galleries to pose in front of art, be it with their faces or backs turned towards said art, there is a reason. It is a reclaiming and affirmation of the soft, but important power of the aesthetic quality of life.