After the liberation and civil rights movements of the mid-century, phrases like “Black is Beautiful” came to epitomise Black empowerment. In recent years, films like Dark Girls (2011), brands like Fenty Beauty and figures like Lupita Nyong’o in Hollywood, Zozibini Tunzi in the pageant world or Anok Yai in fashion have brought more emphasis on the complexities of colourism in contemporary beauty standards. But efforts to celebrate dark skin in popular culture have sparked debate over whether they combat racism or perpetuate fetishization.

A 2022 Forbes article titled What Is Fetishization And How Does It Contribute To Racism? defines fetishization as a reduction of individuals to stereotypes based on race or ethnicity. Fetishization extends beyond sexual desire and can influence preferences and biases, which can perpetuate harmful narratives and contribute to systemic racism. In art and literature, racial fetishization is often mistaken for character building and can manifest as a stereotypical depiction such as exaggerated story lines, mannerisms or skin tones.

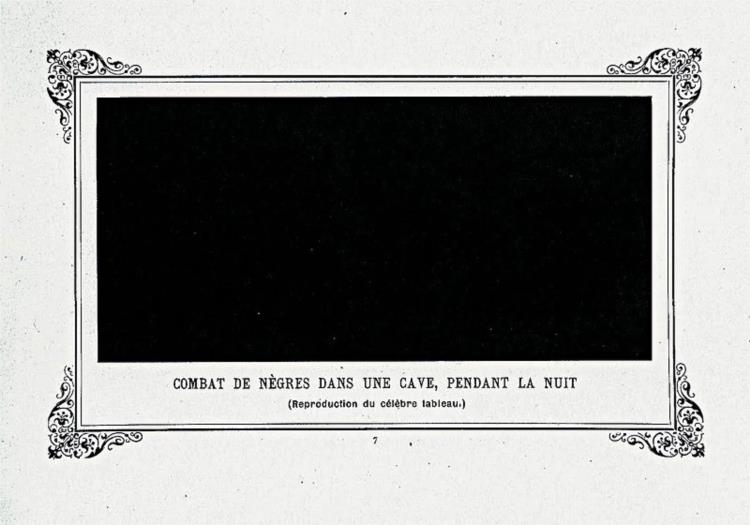

Racial fetishization is also known as negrophilia. It shows up blatantly in popular culture where the objectification of Black culture through cultural appropriation and Blackfishing, is freely championed by figures such as Kim Kardashian and Rachel Dolezal. But the commodification of Blackness, and perpetuation of racial “othering” is most sinister when hidden in the seemingly critical enclaves of the art world, as I wrote in an Ephemeral Care article. In art, fetishization and aestheticization are often quite inextricable.

In The Color Fetish (2017), Toni Morrison explored the use of skin colour, especially examining its role in American literature. Using examples from William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway, she showed how colourism in literature is used to shape characters and plots, thus serving as a narrative shortcut. Morrison advocated for a more nuanced storytelling approach and shared her efforts to subvert colourist narratives in her own work, prioritizing character development over racial identity.

Despite Morrison’s critique, exaggerating ethnic features can be an extremely useful tool and its potential is exponential in the hands of Black folk. In South Africa, many artists such as Zandile Tshabalala, Boemo Diale, Cow Mash, Wonder Buhle Mambo, Sthenjwa Luthuli, Sphephelo Mnguni, and Zanele Muholi have opted for the blacked-out Black body trope, which has seen phenomenal success. The question then becomes not whether this tool is useful, but rather whether or not its efficiency is by design and to what end.

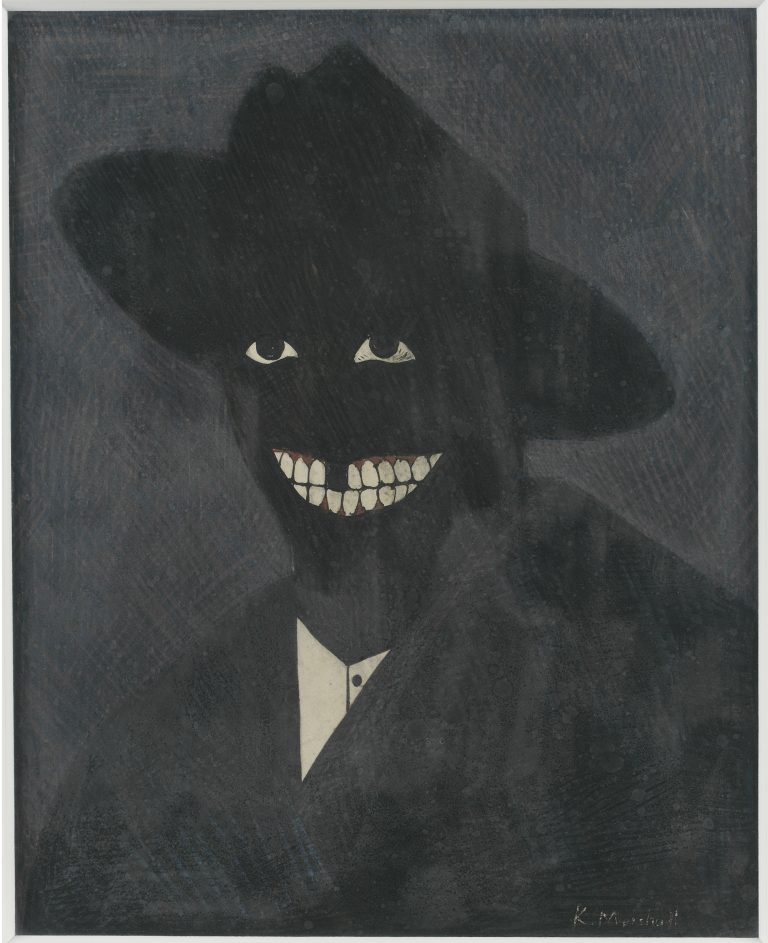

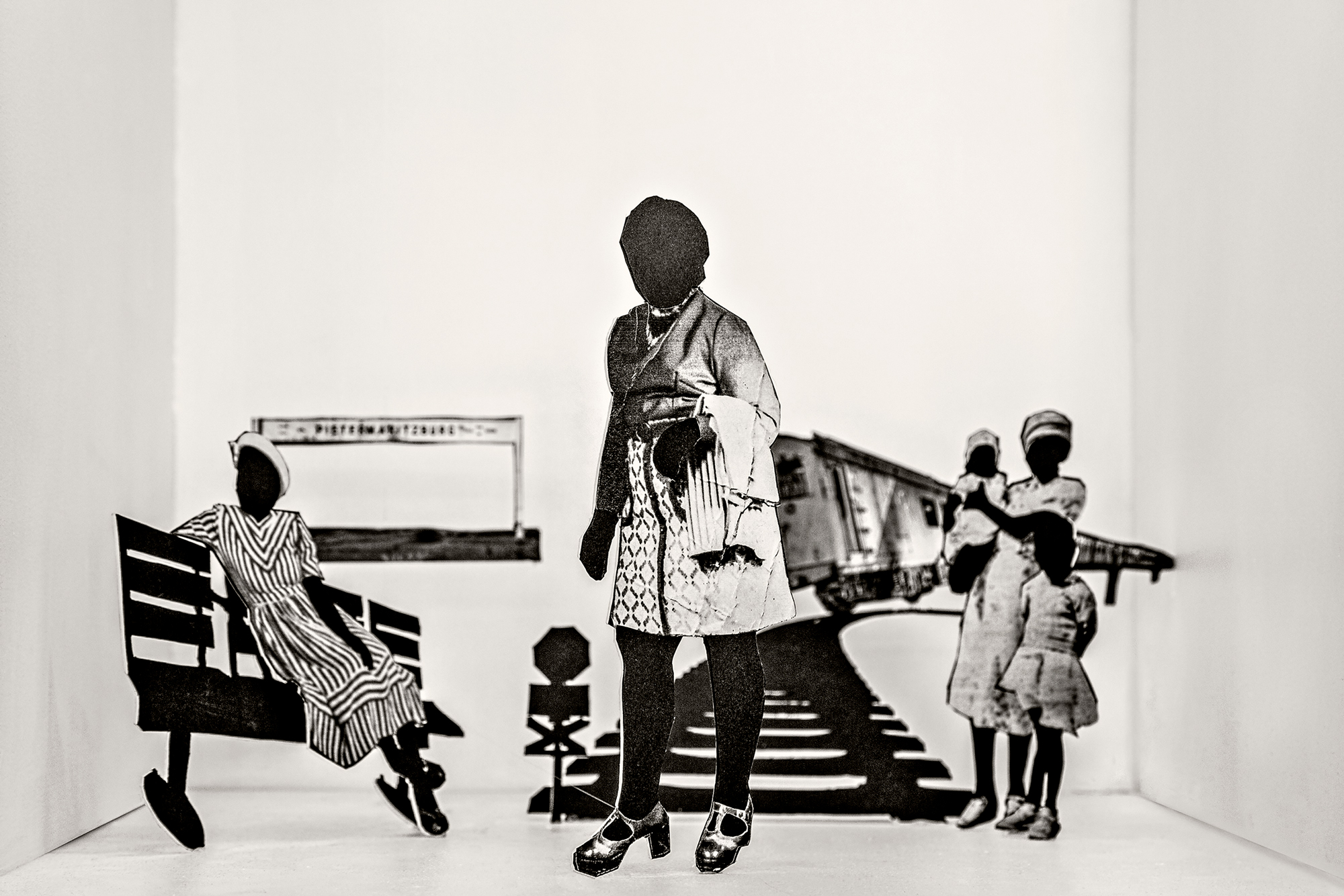

In African American art, there are plenty of examples of the fetishization of Black skin being used critically. Kerry James Marshall is known for his figurative paintings, sculptures, and photographs that feature ultra-dark skin tones to affirm Black identity and challenge the absence of Black figures in Western art. Kara Walker, in works like Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War (1994), similarly uses Black figures devoid of contours or shades to confront viewers with the harsh realities of racial violence.

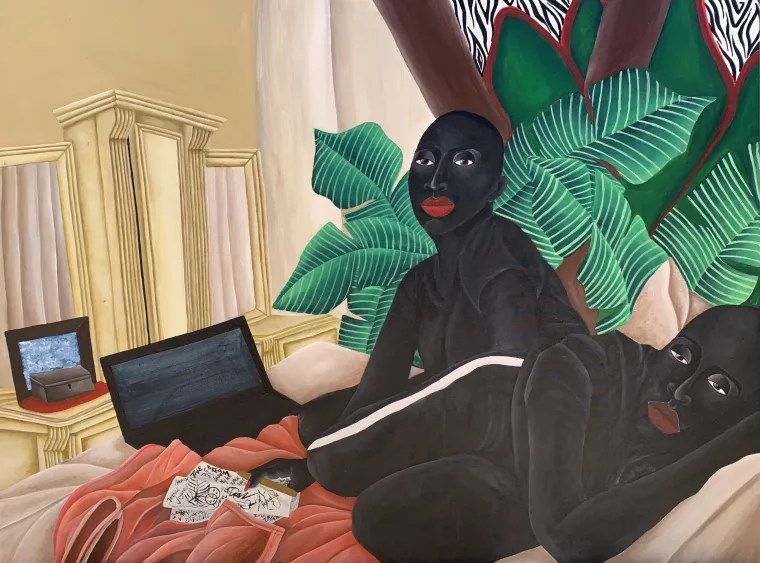

But of course, the South African depiction of very dark figures hits different. In a Mail & Guardian article, Palesa Segomotso Motsumi describes Zandile Tshabalala as “careful to not touch on too many issues … She interrogated the notion of black women being stationed to a singular position, one that is docile and domesticated … conjures up ideas of black bodies in pleasure and rest, deafening the pervasive, Western art practice of the erasure of black bodies.” How ironic especially as the article simultaneously notes Tshabalala’s global appeal.

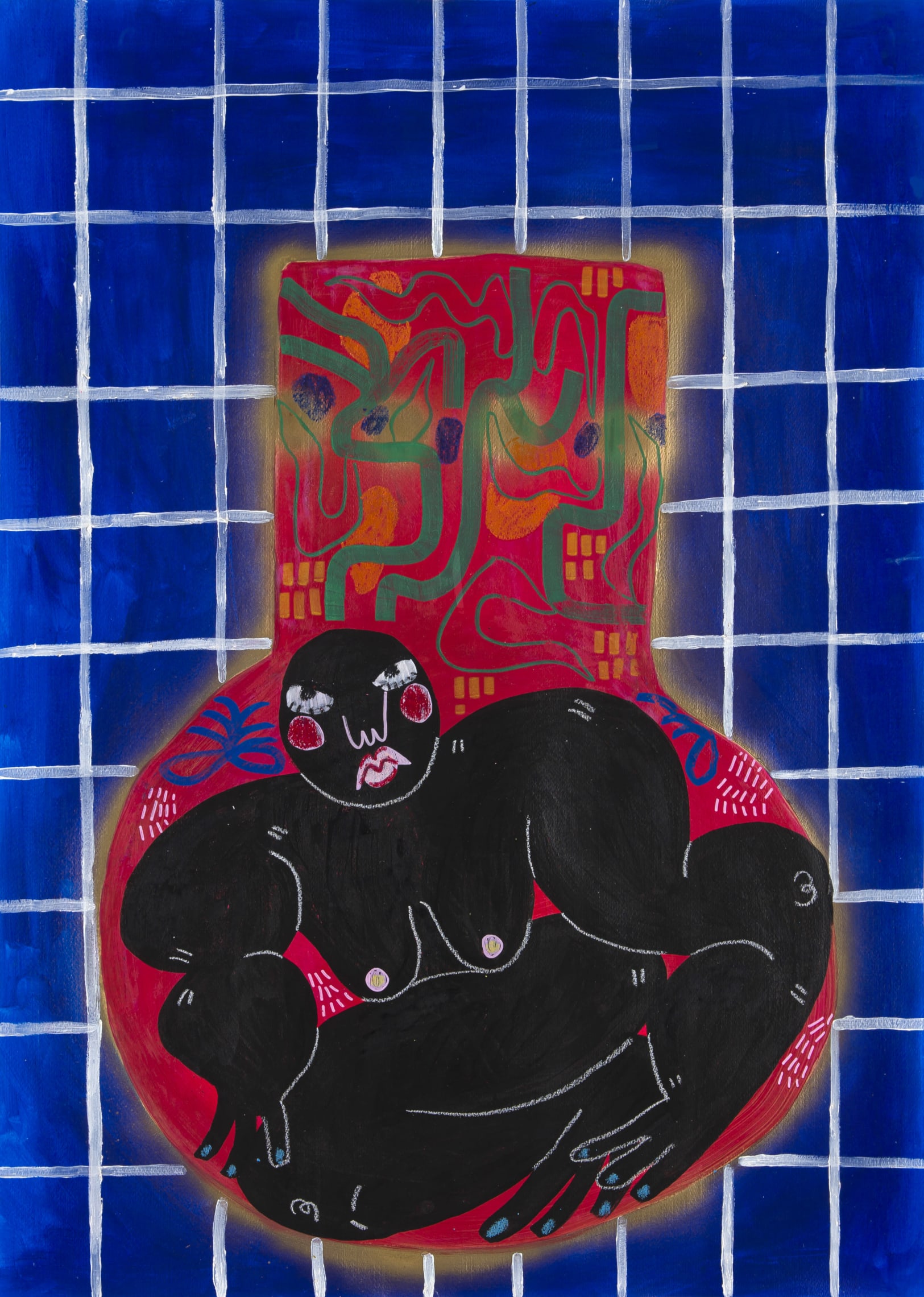

Similarly, Boemo Diale, this year’s recipient of the Tomorrows/Today Prize from the Investec Cape Town Art Fair has been lauded by the art world for her own ultra dark figures. An arrtskop.com article wrote: “Boemo Diale’s engagement with her heritage is more the function of a personal reckoning with her own nuanced existence, devoid of any direct political statements. Her use of colour – bright pink, yellow, green, red – and embellishing her characters with tattoos is more about engaging with the aesthetic reality of racial ambiguity than it is about, say, confronting and addressing social prejudices.”

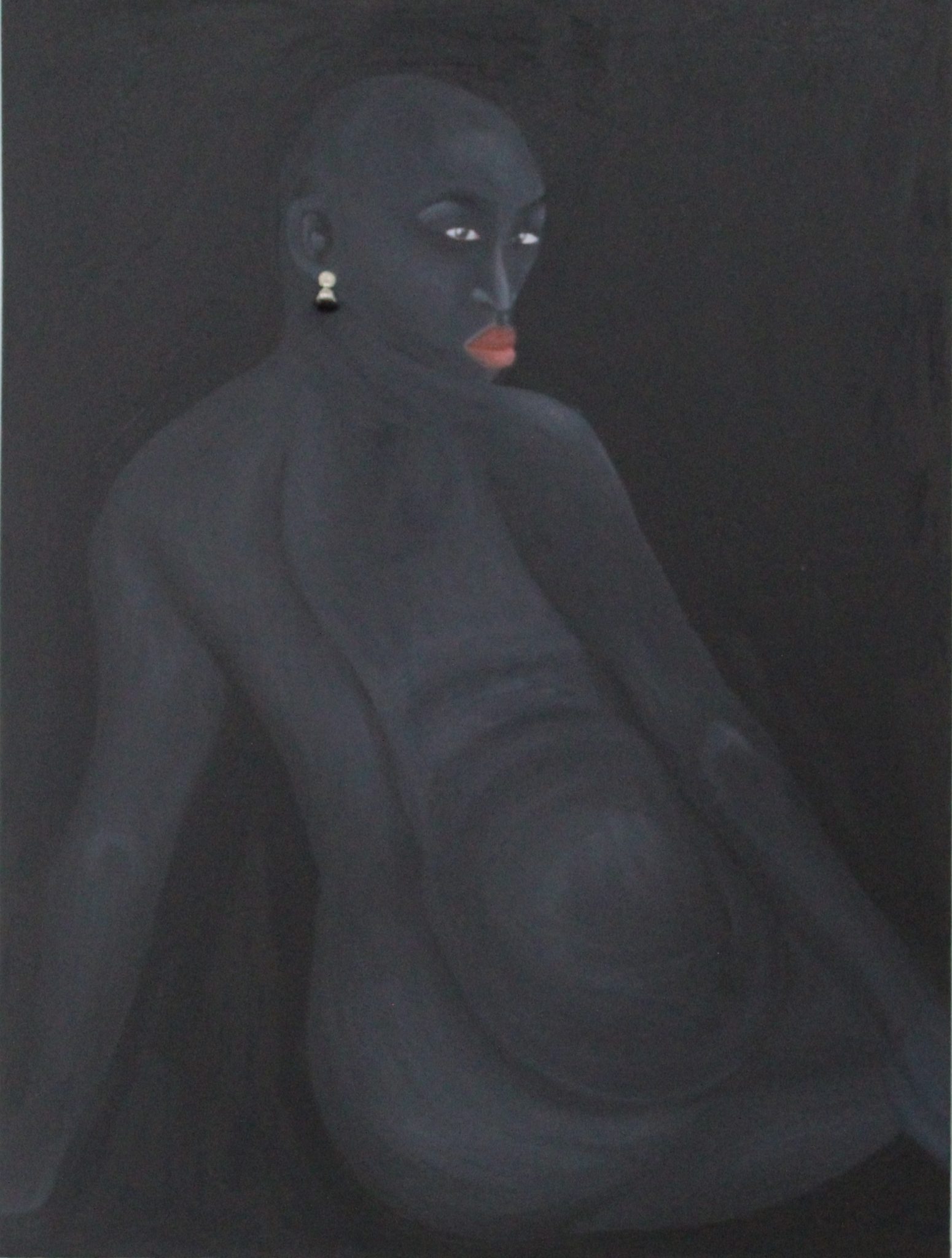

In her recent solo exhibition Re Gona (2024), Cow Mash attempted to explore the role of Blackness in shaping collective identity by using Black as both a literal and metaphorical element. Engaging both her Blackness and her womanhood, Mash used the uniformity of the colour to signify the complexities of race, identity, and belonging. Through this exhibition, which also seemed to straddle the line between man and beast, woman and object, Mash was said to be honouring Black presence in contemporary culture and inviting viewers to engage critically with their own perceptions and prejudices.

Where these explorations will lead is yet to be seen, and this text is a mere observation of what may turn out to be a passing fad. While some may be critical of such oversimplifications of the Black body and their proximity to the white art market, others may be inspired by the utility of axiomatic Blackness. Black artists who use this trope bear both the blessing and burden of negrophilia, seemingly (perhaps rightfully) serving inevitable preferences for certain types of Blackness while other forms remain more firmly in the dark.

Peripheral Perspectives and the Question of the Land. Image courtesy of Artthrob.co.za