I love to take note of the artistic choices and motifs in television and film that go in and out of fashion over the years. It’s interesting to see how the creative zeitgeist can effectively erase entire popular motifs without a trace. To cite something possibly trivial within my short lifespan of media consumption, for example: whatever happened to anvils? Or grand pianos? If you were the kind of child whose eyes were glued to cartoons, bouncing between channels 302 (Boomerang), 301 (Cartoon Network) and 305 (Nickelodeon), like I was — you would likely have come across the hilarious trope of an anvil or a grand piano falling out of no where. It’s really inexplicable, looking back at it. Why those extremely heavy objects in particular? Did they carry meaning beyond the humour they bring as we watched them crash towards cartoon characters? I still don’t know, but it has been interesting to witness how our more modern cartoons have completely done away with this trope. As out-of-no-where as they appeared, so too out-of-no-where they disappeared. If we turn to even more recent, ‘adult centric’ media, joining anvils and piano in the void of absentia is that which once seemed so fundamental to movies and TV as we once knew it: extras.

still from Looney Tunes cartoon

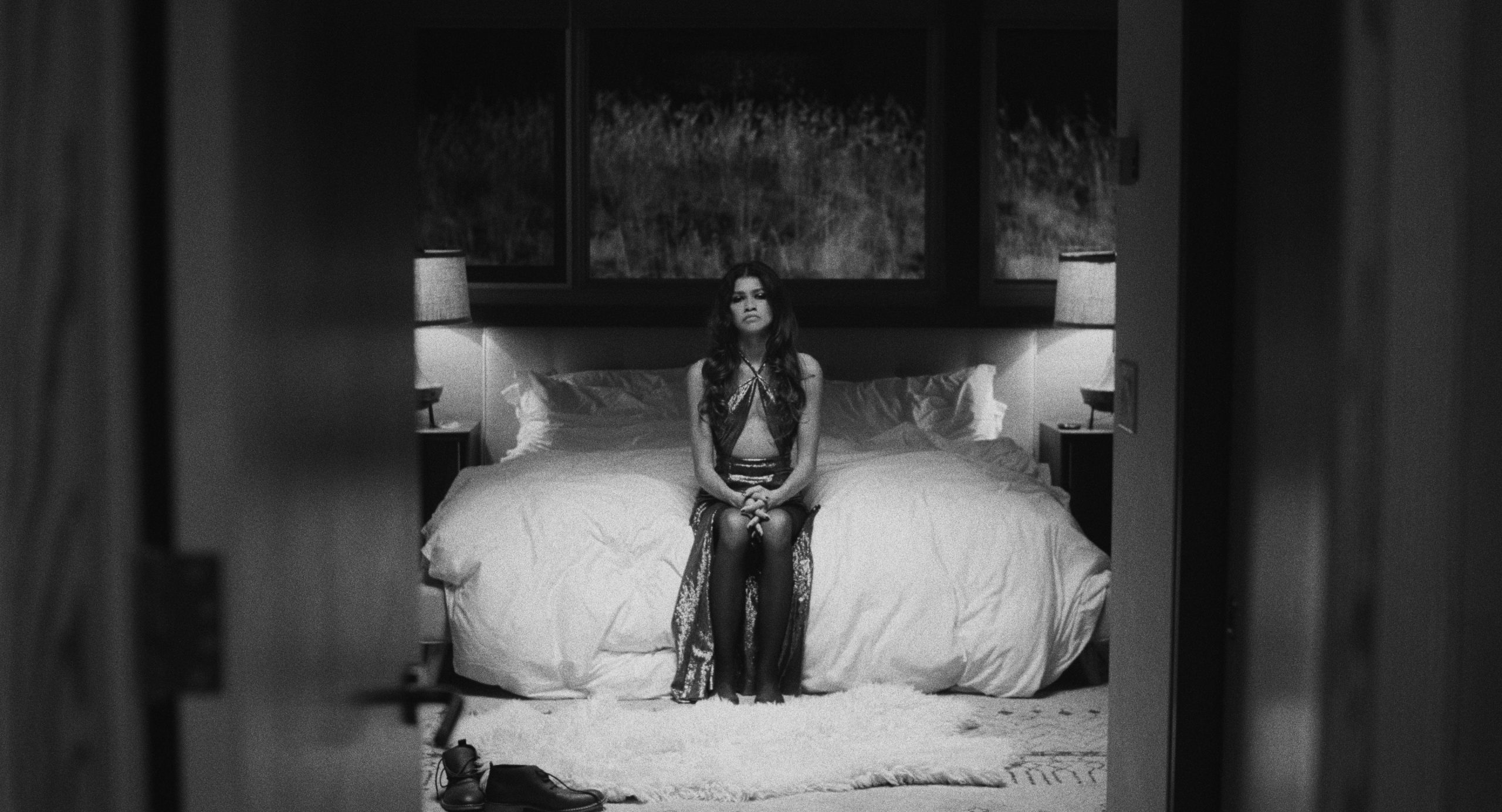

I’m talking about bartender no. 2 in the credits. The Black characters on Friends who would deliver a line or two. Those extras who ultimately aren’t thought of as significant to the plot but rather, aid in filling the frame and giving depth and a sense of reality to the main characters’ lives. Far gone are the days of Charlie Chaplin and over-exaggerated slap stick performances. Audiences seem to want believable characters. And the new best way to achieve this seems to be through populating cinematic works with people outside of the main characters — in name and narrative only — while forgoing their physical existence in the movie itself. Now, throw COVID-19 into the mix, both in our real and filmic worlds and what comes out of this is a movie making method and aesthetic leading to the creation of movies like Malcolm and Marie. The Levinson film that features Zendaya and John David Washington going at it for just over 90 minutes. Throughout the film, they make reference to other characters like the white critic, other famous directors and Malcolm’s chosen star, Taylor. None of whom actually ever show up in the luxury house that the entire film takes place in. The crew on set was equally as bare, with Zendaya having done her own makeup and styling for the film, so as to keep the set as socially distanced as possible. The film’s undeniable tension is further built up by the fact that the characters can’t seem to (nor want to) get away from each other. It’s like a build up to Steven King’s The Shining.

Zendaya in Malcom and Marie

still from Boys in the Band

And it isn’t just this film. It’s Ryan Murphy’s take on Boys in The Band, which takes place with a small cast attending one dinner party and virtually never leaving the apartment. It’s Chadwick Boseman’s swan song, Ma Reiny’s Black Bottom, where the bulk of the film takes place with the small ensemble working on a record within a single recording studio. The latter does admittedly have a few scenes with extras, however, even those easily quantifiable number of scenes are a major difference. The media content we are seeing on our small screens has a deeper “smallness” to it, an intimacy. Without the density of the extras, the films produce the atmosphere similar to that of plays. American Son (2019, Before.COVID) craftily blurs the lines between film and theatre production, having been adapted from the broadway stage to Netflix’s screen in an unprecedented ways. It didn’t detract from the “rawness” often experienced in theatre by adding new characters, new sets or new scenes; nor did it diminish the complexity of film by reducing it to a camera filming the stage.

Chadwick Boseman in Ma Reiny’s Black Bottom

With the film industry having been majorly slowed down over the last year, there was all the opportunity to plot the next moves forward. From the looks of it, those next steps forward seem to be a return to more traditional storytelling. The cultural move seems to be towards an epiphany that the confines of the stage and more limited set and cast, doesn’t have to be limiting at all. There’s so much room for the characters themselves to be full and complex without frivolous cuts and one liners. It’s something more attune to the chaos and incoherency of life watching two characters in dialogue for a prolonged period of time, as we witness them contradict themselves and go back on earlier sentiments. While there’s nothing wrong with the extravagance of Baz Lurhman-esque productions, it’s always interesting to watch the film industry reshape itself upon our screens. For now, that reshaping looks like a shedding. Where Lurhmaan’s 20s — imagined in his Great Gatsby adaptation — were filled with a lot more confetti, fast cars and extras. The 20s we live in now are a lot more silent, yet still just as fast. Who knows what cinema will look like just in the next year? I keenly look forward to who and what might spring from out-of-no-where.

Kerry Washington and Steven Pasquale in American Son