As a nihilistic sex worker who is typically shunned by every social group I come into contact with, baddie culture was once a safe haven. Back then, being a baddie meant that as a marginalised womxn, your power lay in your ability to take the sour lemons life laid at your feet and make sweet lemonade! And no—I don’t mean that in the Beyoncé sense.

Baddies were womxn who were truly bad. The womxn society wanted to pretend didn’t exist. Strippers and anarchists! Womxn who were not delicate or demure. Womxn who had big asses and even bigger voices. These womxn had existed so long on the margins, they no longer needed your love. Instead, you were the one who began to crave their love and by then, it was no longer free. Their survival became an act of refusal. An exceptionally sophisticated refusal to squander desire.

The term “baddie” first gained traction in the mid-2010s, primarily within online platforms. It became popularised by adult entertainers who had achieved mainstream success despite societal stigmas surrounding sex work. Figures like SZA, Tommie, Nene Leakes, Tiffany Pollard, Azalea Banks, EVE, and more started on the pole and became celebrated baddies. Even megastars like Rihanna, Megan Thee Stallion and Nicki Minaj, who didn’t start on the pole, but banked on the aesthetic have come to be known as big-time baddies.

But Amber Rose, Blac Chyna and Cardi B in particular, are the undisputed giants of baddie culture. Prior to Amber Rose, the Internet had never seen a racially ambiguous popular femme figure with a thick physique and an unapologetically hypersexual persona. During a 2016 episode of her online radio show Loveline (2016-2018), Rose spoke on her past as a stripper named Paris, saying: “When I was stripping it was the best time of my life.” Her advocacy includes the SlutWalk (2011), which promoted sex positivity and sex workers’ rights.

Blac Chyna also made her start as a stripper at Miami’s King of Diamonds Gentleman’s Club. She rose to fame when Drake mentioned her in his song Miss Me (2010), attracting Rihanna and Nicki Minaj’s attention. In 2015, Amber Rose and Blac Chyna made headlines for their appearance at the Ace Of Diamonds Club. According to TMZ, the pair showered strippers with $10,000 in crisp bills while twerking together, expressing their love for the game.

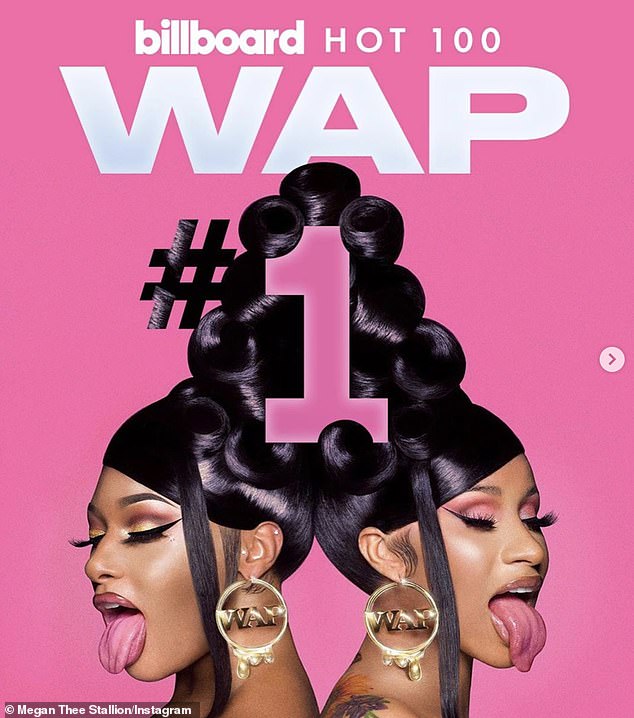

Cardi B’s impact on baddie culture is also undeniable. Her almost militant celebration of black femme sexuality is exemplary. She started stripping at 18, made her way into Love & Hip Hop New York (2011-2010) and eventually became a chart-topping musical artist with smash hits like WAP (2020) featuring Megan Thee Stallion. With a massive social media following and tabloid romance, Cardi has been recognised for her bombastic, loud and unapologetic persona. She is one of the outstanding remnants of what baddies used to be.

Nowadays baddies embody the “every woman” aesthetic, but the early baddie’s look was a lot more specific. She typically had a curvaceous figure with a full bust, slim waist, wide hips and a big ol’ ass. Her facial features were always curiously ambiguous, with her nose, mouth and eyes often being described as exotic. Baddie culture has intersected with other elements of black culture like Hip Hop and streetwear. Many of the biggest baddies have been girlfriends, wives or baby mamas to some of the most influential Hip Hop stars.

One of the most intriguing convergences lies within the symbiotic relationship between reality television and baddie culture. Shows like Love & Hip Hop (2012-present), The Real Housewives of Atlanta (2008-present) and Baddies (2021-present) feature ex-strippers turned models, business owners and artists. But while these shows provide visibility, they raise concerns about the differentiation between entertainment and lived experience.

Diminishing the contributions of black womxn emerging from the adult entertainment industry compromises our grasp of baddie culture. The unapologetic attitude central to the baddie persona often stems from past experiences of sexual objectification, abandonment, trauma and violence. This boldness can lead to physical altercations, as depicted in the aforementioned shows. This behaviour should not be condoned, but it must be understood.

Another issue is that securing the bag seems to be the main objective of being a baddie. It essentially encompasses more than just monetary gain, but baddie culture has warmly embraced capitalist ideals. Despite their financial success, many baddies never retire, perhaps for fear of returning to poverty or from societal pressures to maintain a certain image. Considering the comparatively privileged backgrounds of newer baddies, the constant pursuit of wealth can paradoxically result in economic exclusion.

Indeed, the very foundation of baddie beauty standards is enmeshed in problematic innuendo. Its aesthetic principles seem to be driven by outdated societal norms built to bar black womxn from being perceived as “basic”, accentuating certain features such as light skin, eye shape, nose slimness and straight hair. Rooted in respectability politics, these efforts are designed to distance black womxn from Afrocentric attributes and confine beauty based on that distance.

The prominence of baddie figures can also limit the self-actualisation of young black womxn by perpetuating harmful stereotypes and bad body image. The rise of dangerous procedures like BBLs (Brazilian Butt Lifts) reflects this dark side of baddie culture’s impact on beauty standards. While figures like Biggie and Rolly from Baddies defy baddie norms with their racially unambiguous appearance, it is their fair-skinned and slim-waisted counterparts who often receive more mainstream recognition.

Baddie culture’s mainstream success has also resulted in a detachment from its roots, now representing any self-assured, fashionable womxn embodying financial success. This cultural appropriation results in a form of erasure exemplified by figures like Kim Kardashian. It’s as if Kardashian took the How To Be A Baddie master class, adapting her appearance and engaging in relationships with famous black entertainers, including a sex tape release with Ray J and a marriage to Kanye West, helping her achieve fame and financial success.

Through influencers like Kardashian, driven by social media platforms like Instagram, Twitter and TikTok, baddie culture has become a significant cultural phenomenon. It has led to the rise of platforms like OnlyFans, which offer individuals a safe space to express their sexuality while monetising their intimate content and attaining financial independence.

But before being a subculture, being a baddie is an instinct. Call it survival instinct. Drawing inspiration from sex work, black culture and the digital sphere, baddie culture continuously evolves and adapts. Within its universal liminality, there remains a palpable sense of refusal. A sense which justifies identifying it as a black feminist movement that, though it may no longer be ours alone, may have changed pop culture forever.

Images courtesy of Internet archives