This title may come across as clickbait, but it is not entirely unfounded. According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the literacy rate in Africa was estimated to be around 64% in 2018, which is below the global average of 86%. Data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators shows a lower availability of books per capita compared to other regions. More specifically, Sub-Saharan Africa has exhibited the lowest youth literacy rates, reported at 70% in 2011 by the African Library Project.

Photograph by Ismail Salad Osman Hajji Dirir

Ancient civilizations, Arabic influence, colonialism, indigenous knowledge systems and the fourth industrial revolution play significant roles in the history of African literacy. Prior to new languages and scripts being introduced by external influences, ancient African civilizations had their own information systems. While Africa’s strong oral traditions contribute to lower reading rates, they do not account for nor imply an inherent disinterest in reading.

Instead, socio-political factors may play a larger role in our reluctance to read. Economic subjugation has been shown to limit opportunities for self-discovery, contributing to lower reading rates. Inadequate infrastructure and insufficient educational systems inadvertently affect reading habits. Despite these challenges, Africa’s rich literary culture and growing interest in reading fuel ongoing efforts to enhance education and literacy on the continent.

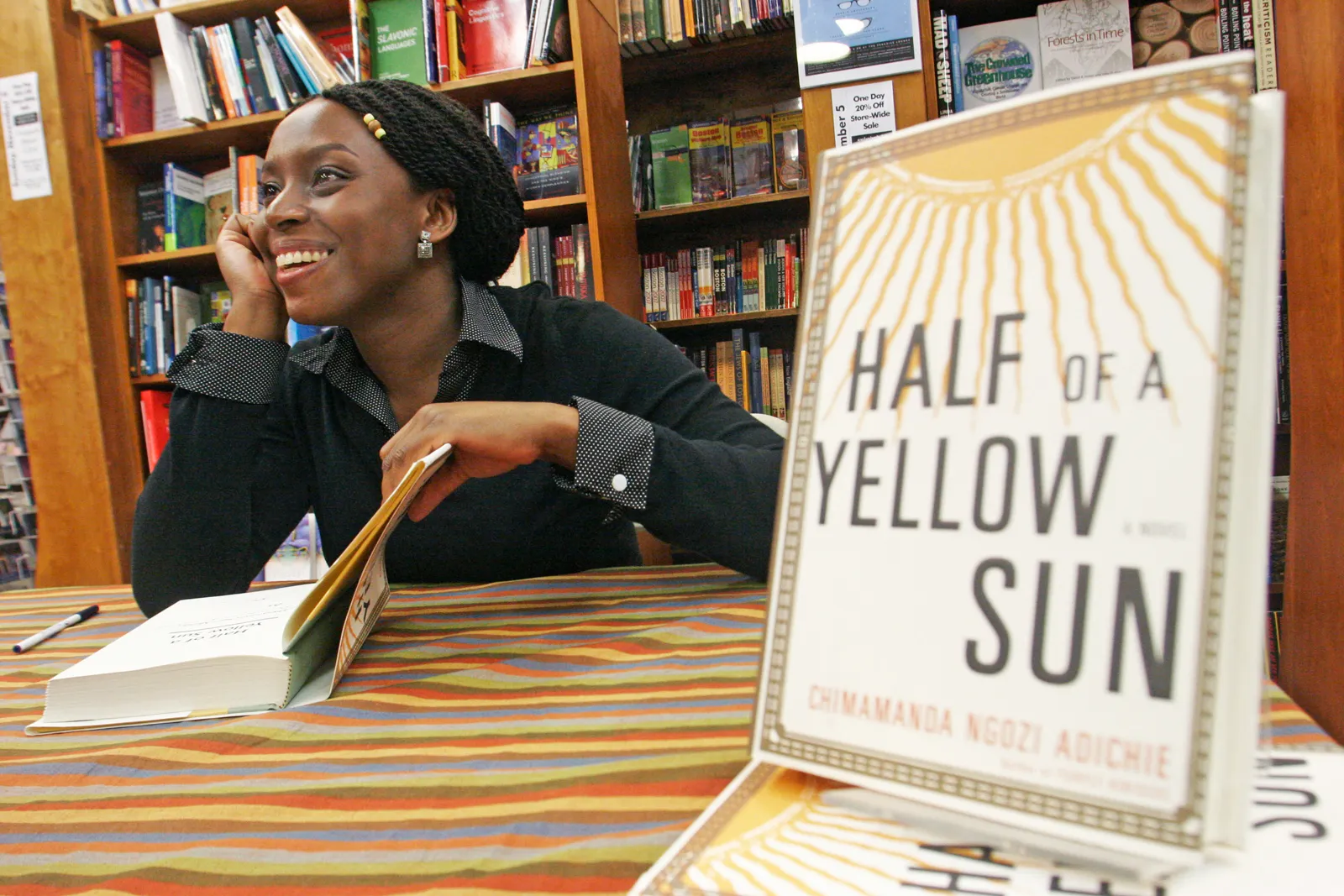

Renowned African authors such as Achebe, Adichie, Soyinka and Thiong’o inspire young African readers with their thought-provoking works. Book fairs, festivals, libraries, schools and community centres, along with the support of governments, organisations and NGOs, actively work towards improving literacy rates through various educational initiatives.

Chinua Achebe

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Images courtesy of Britannica

While efforts to promote literacy in Africa are acknowledged, it is imperative to recognise that the desire for widespread literacy is not universal. Illiteracy can serve supremacist interests by limiting political participation and access to information in the global South. In Africa, misinformation, propaganda, censorship, diversion tactics and the spread of conspiracy theories are commonly used to maintain subjugation.

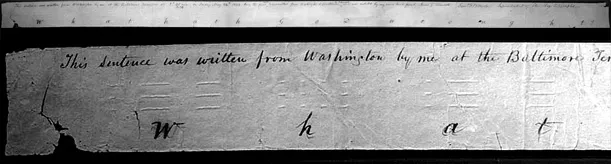

Popular media has long been exploited for the manipulation of collective awareness, revealing the impact of emerging technologies on global epistemologies. Between the 15th and 20th centuries, the global North had prioritised scientific and territorial progress, with inventions like the printing press, electricity and railroads, driven by colonial ambitions. Eventually, the advent of the Telegraph revolutionised information exchange, and the invention of the Internet further privileged speed and novelty over context and comprehension.

Image courtesy of Library of Congress Corbis VCG via Getty

An image of the first telegraph message sent from Baltimore to D.C. in 1844

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On one hand, contemporary technologies do enhance the reading experience through customisable features and other interactive elements. Digital tools like e-books benefit readers with disabilities and empower authors from all walks of life. Social media and online reading communities consistently foster human-to-human connection, while reading analytics improve content through data analysis and artificial intelligence.

On the other hand, smartphones and other personal devices lead to shorter attention spans and a preference for bite-sized content. Social media platforms divert focus with notifications and other social cues, while multitasking habits hinder sustained engagement. Skimming for specific information has replaced deep reading, spreading superficial and inaccurate content.

Social media’s impact on education is embodied by platforms like YouTube and TikTok, which blur the boundaries between entertainment and learning. These platforms may enthral younger audiences with visual stimuli, but they arouse concerns around mass manipulation by means of algorithmic ‘suggestions’. On these platforms, young Africans face the risk of unwittingly (re)surrendering to perpetual states of subjugation.

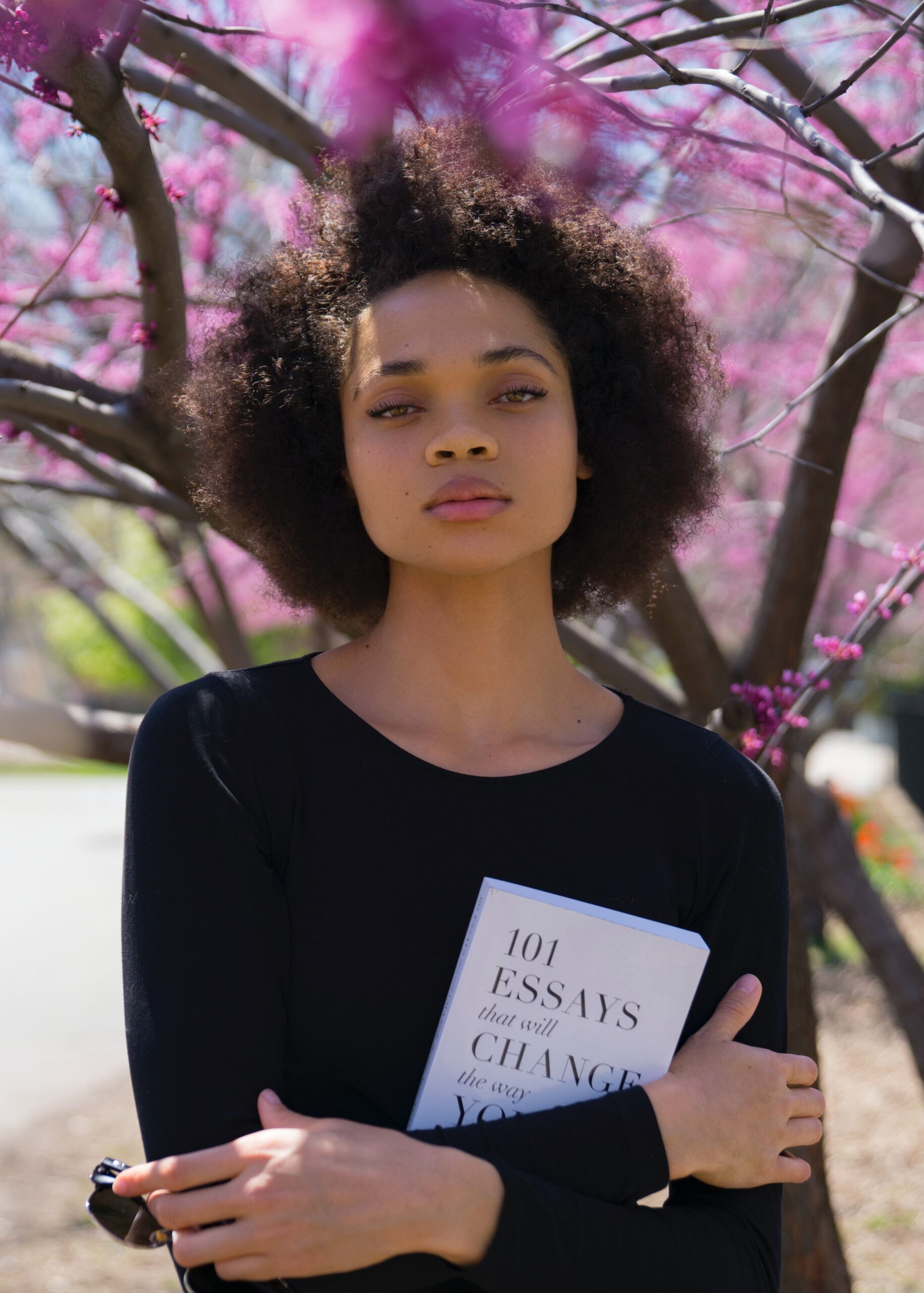

Photograph by Bruce Mars

Photograph by Fausto Garcia Menendez

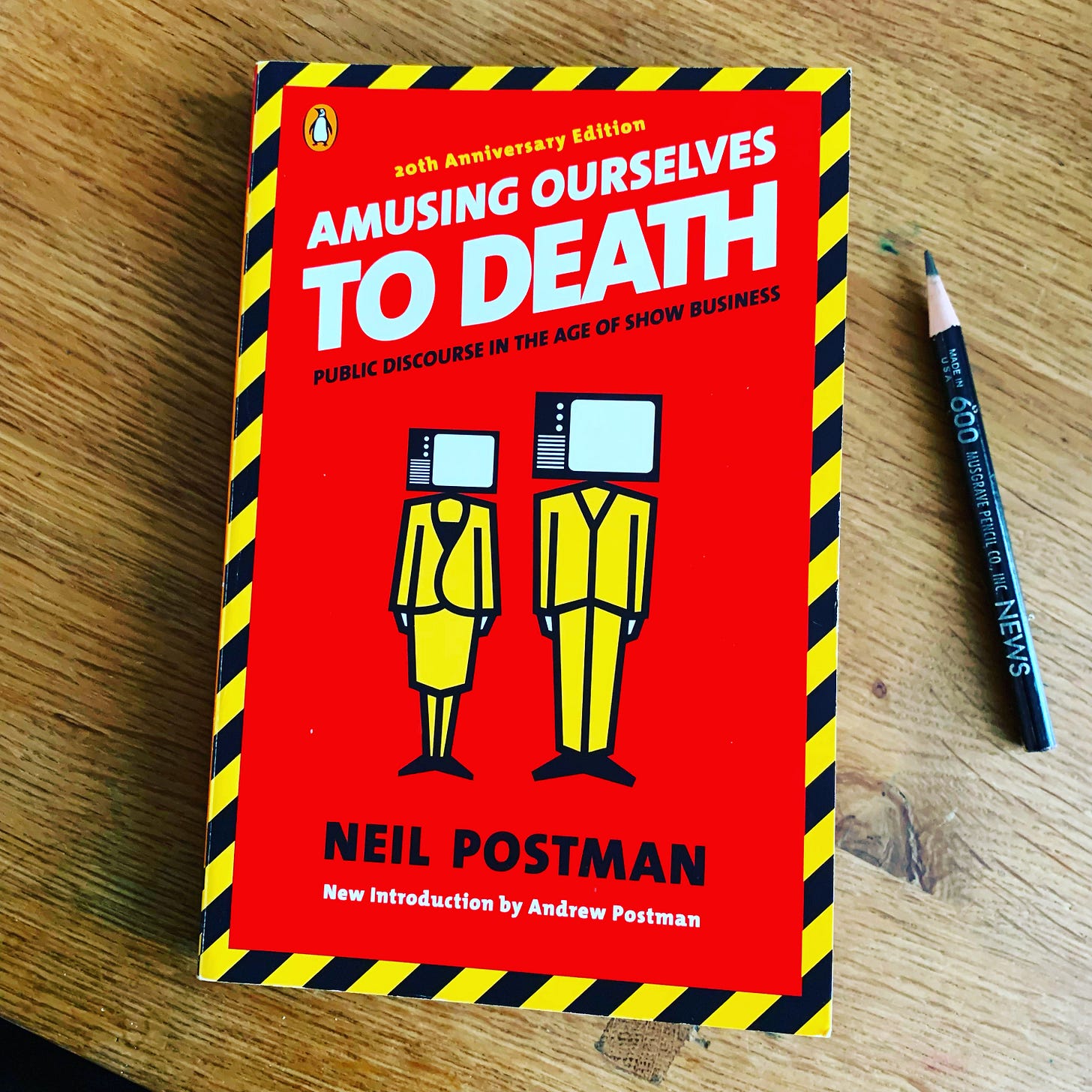

Of course, your humble narrator is not the first to voice such concerns. Much has been written on the matter, and dare I say, reading on the subject of reading, or lack thereof, is particularly compelling in its meta nature. Neil Postman’s book, Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985) highlights the consequence of media making us mistake ignorance for knowledge, prompting us to question the information we consume and its influence on our perception of reality.

Photograph by Abdul Ahad Sheikh

More pertinently, iconic literary works like George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), interrogate distinct forms of mass oppression. In 1984, Orwell portrays an authoritarian government that surveils each individual’s actions, enforcing uniform attire and attendance at communal ceremonies. Conversely, Huxley’s, Brave New World depicts a society where individuals willingly consume soma, a pill that perpetually induces pleasure, but facilitates brainwashing.

While Orwell’s 1984 operates as something of a warning against external oppression, Huxley’s Brave New World cautions us against the dangers of becoming so accustomed to oppression that we actively participate in it. Where Orwell’s concern lay with those who sought to prohibit books, Huxley’s apprehension centred around a future where there would be no need for book bans since there would be a lack of interest in reading altogether.

One needn’t read every book on earth to surmise that access to and appetite for authentic information are intricately linked to how instruments of power are wielded. Yes, platforms like YouTube and TikTok are a helluva lot of fun, but they are also deliberately dangerous distractions and deterrents for those who try to truly learn. Ru Paul prophetically popularised the phrase “Reading is fundamental!” as if for this very purpose. If you’re not catching the shade, I’m saying: Read more! The forlorn ritual may be the last key left to unlock your liberation.

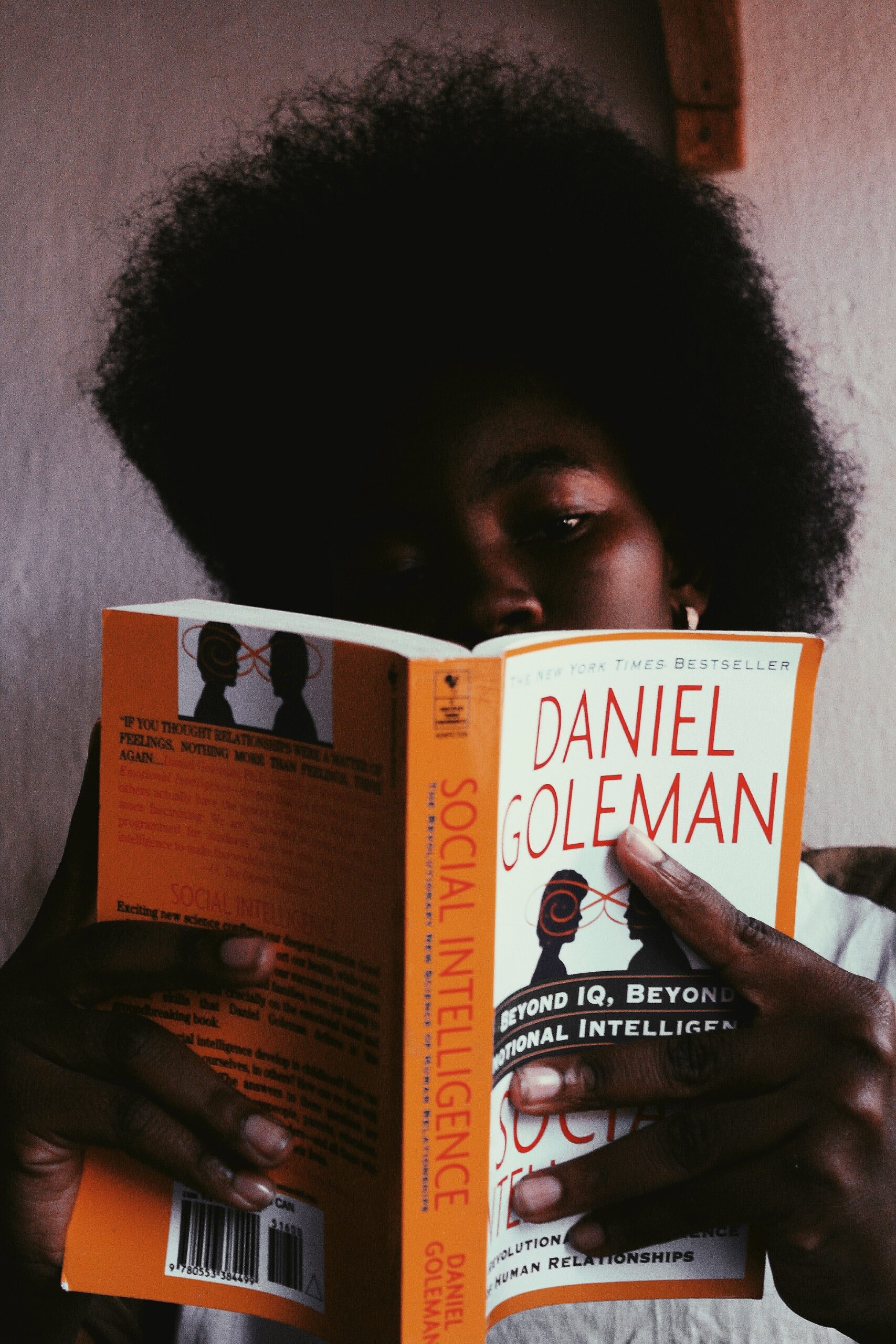

Photograph by Bansah Photography

Photograph by Thought Catalog

Photograph by Muhammad Taha Ibrahim

*Thumbnail photograph by Suad Kamardeen