It’s fascinating how we can measure the changes in the world around us.

Some changes show themselves cyclically, like the leaf’s change from green to brown to green again, and so forth. In the more material world, we remark at the price of things constantly increasing around us.

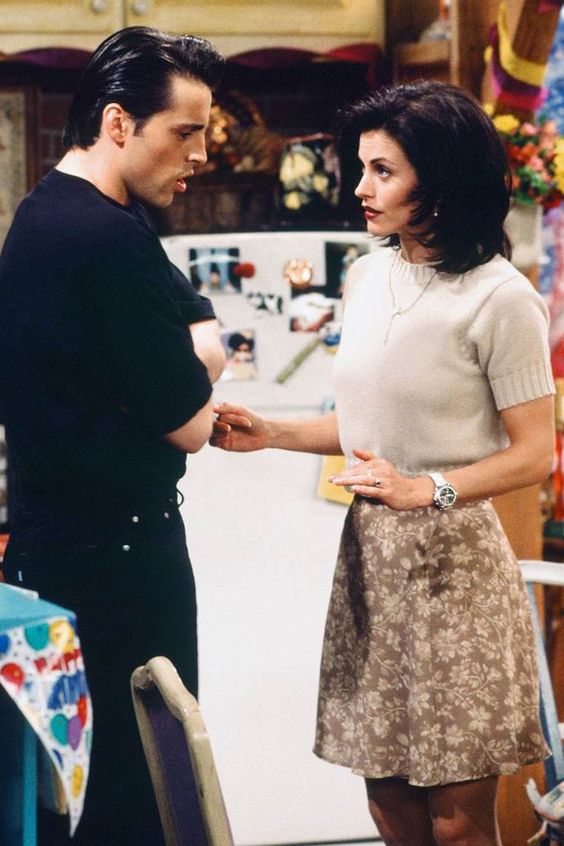

I was taken aback when in conversation with a millennial who had gone to university in the year 2000, he remarked: “The biggest difference on campus is that people dress like characters we only used to see on TV.”

Without giving it much thought, it makes sense. Of course, we could ask questions that prod deeper into the statement, like which TV characters and in what way? And of course, there’s an argument to be made that the selection of our clothing is naturally inspired by the overbearing presence of the west in our media. You are what you eat, or something along those lines.

But how did we get to even having access to these clothes?

On 1 January 2005, the Global Fashion and Textile Industry abolished the global quantitative quotas. This essentially meant it was open gates and a free-for-all for all fashion markets, allowing for retailers to start sourcing a higher quantity of clothing for a cheaper price.

All at once, as the world collectively took a deeper step into the new millennium, more and more “MADE IN CHINA” labels could be found stitched into the back of clothing. And conversely, with every import, more and more cotton mills in South Africa closed down due to a lack of demand.

It’s a tricky crossroads South Africa has found itself at. In the 17 years since the abolishment of the quota, fast fashion has been rife in the country. In 2022, if you know what you’re looking for, you can find SHEIN items pretty much everywhere. Although it’s hard to keep up with all the SHEIN drops, given that the fashion giant releases up to 6000 styles daily. In fact, in July 2022, China produced 3.29 billion meters of fabric. And of course, as the largest online fashion retailer continues to grow, they are 6 different outlets across the country.

On the other hand, in more positive news, South African designers of the millennium have made waves across international waters, having displayed in fashion shows across the world. The international abolishment of the quota, albeit problematic in its own right, has opened South Africa up to the global language of fashion. It’s a global language, divided only by different dialects, inspired by the locale of the garment.

The best example in most recent history was the exciting fashion exchange orchestrated by Vogue, including Thebe Magugu (of the eponymous South African fashion house) and Pierpaolo Piccioli (of the iconic Vogue). In receiving each other’s garments, they exemplified the respectful potential of fashion in making something your own, without appropriating it.

In a way, perhaps, that’s how we look like the characters on TV. We swap out their classic Reeboks for Nao Serati’s most recent collaboration with the sportswear brand for South African pride.

But then with the cheap allure of the fashion giant that is SHEIN, how much of “our own” can we make these clothes?

How much personality can be extracted from the seams of clothing which moves to the fleeting pattern of TikTok trends? Or put into?

Between our screens and our seams, it’s hard to separate where we begin and where we end. The language of fashion, be it a beautiful, universal one, isn’t necessarily one that’s as easy as simply saying “express yourself”.