The 1960s initially witnessed counterculture movements erupt as movements that opposed the rifeness of racial and political injustices that were invading the Western world at the time. The movement popularised many alternate forms of identity and expression, notably the Hippie Movement, whose impact still remains progressive in modern-day society. Even if the conformity to a countercultural mindset may not explicitly be expressed by certain members of our society, we know it is there. The media has displayed counterculture as an influencer of various fashion, cultural trends and discourse conversation. Being a practising, young South African journalist myself, I cannot be complacent about our changing media landscape, especially in a time where alternative media and digital media publications represent the growth of counterculture influences in various spheres of life.

The dilution of counterculture’s meaning has evoked many cultural shifts in the fashion realm, which has evidently aided the rise of varying dressing styles, unconventional designs and core aesthetics that are supposedly contrary to the norm. Even if we can’t decipher between what’s simply different and what’s counterculture today, it’s still worth noting how important media parts communicate and reflect the changes in a way that does not mislabel and generalise ‘counterculture’.

Bubblegum catches up with Writer, Content Strategist and Digital Marketer, Khensani Mohlatlole to consider the prevalence and practice of counterculture in the livelihood of South Africa’s youth, and more critically, find out how it has impacted the function of fashion journalism, as a source of media and influence in our society.

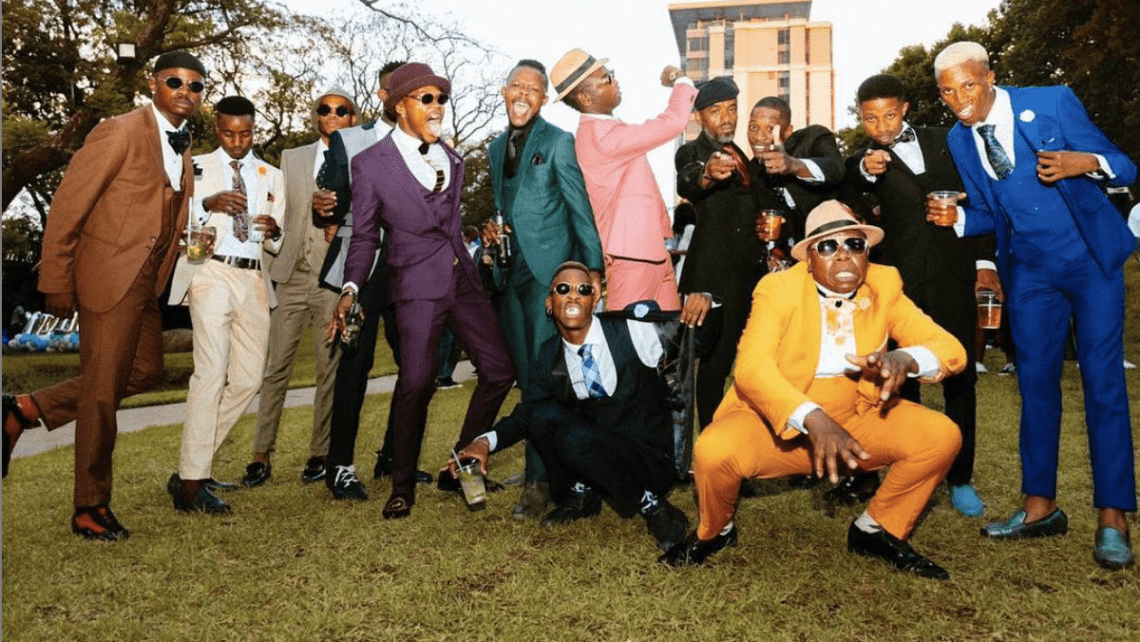

Photography Via Instagram @material_culture

Ruvesen Naidoo: How has counterculture influenced the evolution of fashion journalism over the years, in your opinion?

Khensani Mohlatlole: I think counterculture was a huge driving force behind the rise of a lot of digital and alternative media publications in the 2010s. Covering the Skhothanes, Cape Town street culture, the Botswana Renegades and the like really helped to cement Vulture, Dazed, i-D, and the like as sources for culture and conversations outside of the mainstream. I don’t know if we could say the same today since counterculture is culture now with the continuous rinse and repeat super cycle of trends, aesthetics and cores.

RN: To your knowledge, have there been examples of specific youth countercultural movements that have had a significant impact on fashion journalism, particularly in a South African context?

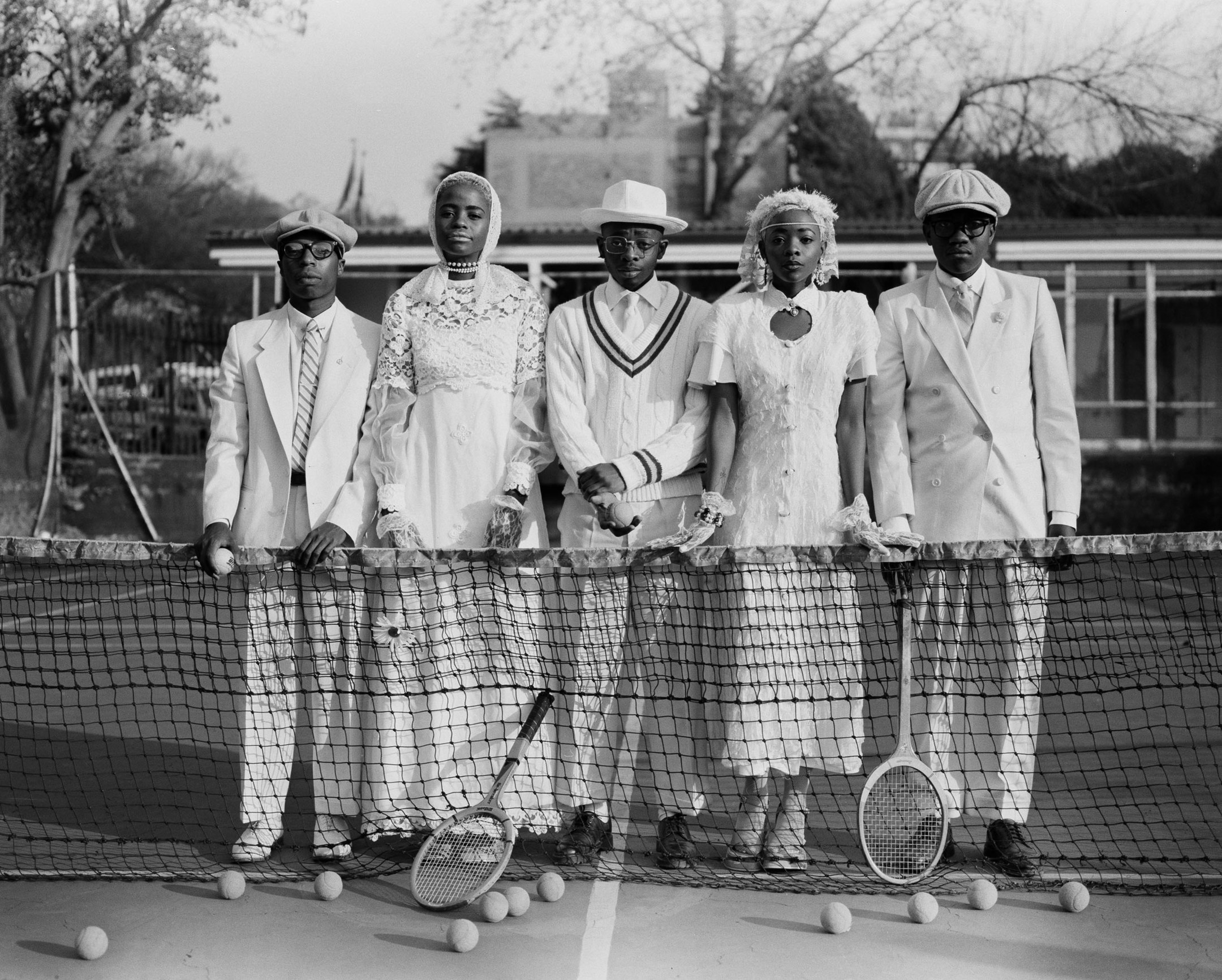

KM: The Sartists, the Skhothanes, and Vintage Cru are a few that come to mind that really held attention in the media. I think contemporary writers and journalists of the time were a part of documenting and explaining the many influences and contexts that resulted in these fashions, especially as it pertained to developing a post-apart identity through fashion.

RN: In what ways do countercultural fashion movements challenge or disrupt the mainstream fashion narrative in journalism?

KM: I don’t know if they challenge or disrupt mainstream fashion journalism. In fact, I think there’s sometimes a predatory way that mainstream media approaches them–looking to be the first to break the story on the next novelty. There’s a meme I once saw about how i-D put together its headlines which basically involved a guy throwing a d**** at a whiteboard with an assortment of racial, ethnic, gender and sexual identities and combining those with art movements, underground scenes and the like to produce something like “the 70-year old Malaysian trans surfers redefining lolita fashion”, you know? In an age when publications are trying to get as many clicks and eyes as possible to court advertisers, they’re thirsty for the most eye-catching absurdities.

RN: How has the rise of social media and digital platforms affected the youth’s perception of ‘culture’ and what is ‘trendy’?

KM: That’s a complex one. I think culture is a little flatter now. Everything exists in the same place all at once thanks to the Internet which is great in being able to cross distance and time to learn about different groups and perspectives but it’s also constantly having to be commodified into a singular core or aesthetic that people can understand quickly and type into a search engine to shop.

RN: How does focus on subcultural movements differ from countercultural movements?

KM: They overlap frequently; usually counterculture becomes a subculture once it’s no longer so shocking to the mainstream.

RN: Can you describe any challenges or ethical considerations that journalists may face when covering countercultural fashion movements, especially since the youth plays a dynamic role in South Africa’s media landscape?

KM: I think journalists have to approach any counterculture with the most care and good faith. It’s important to have the people who are actually within that culture speak for that culture, and for journalists to immerse themselves in such a way that they’re not propping up cash-grabbing in authentics. The other thing is that it’s important not to sensationalise something so as to dehumanise the subjects or expose them to harm from a misunderstanding public.

RN: What role do ‘Gen Z’ and emerging fashion journalists play in amplifying countercultural voices and perspectives in the fashion industry?

KM: They’re the new authorities of taste and culture and they’re doing it in a way we’re not used to. They’re often outside traditional media and gatekeepers and they’re making the knowledge accessible and approachable for all.

RN: Ironically, Has the mainstream fashion industry co-opted countercultural aesthetics or ideas? Does it affect the authenticity of mainstream fashion journalism?

KM: Oh, always. That’s the issue with counterculture under capitalism. Take something like the sustainability and environmentalism movement which started out criticising overconsumption, overproduction and a culture of retail therapy and now there are several mainstream fashion publications trying to peddle ‘conscious collections’ from H&M as an opportunity to buy feeling better about the world dying. Mainstream fashion media was never designed to be authentic, its purpose is to be a middleman between producers and consumers and since the producers foot the bill, it’s always been rather skewed to commercial interests.

RN: From your career experiences, what should young journalists keep in mind when covering countercultural fashion to ensure responsible and meaningful reporting?

KM: What I said before: I think journalists have to approach any counterculture with the utmost care and good faith. It’s important to have the people who are actually within that culture speak for that culture, and for journalists to immerse themselves in such a way that they’re not propping up cash-grabbing inauthentics. The other thing is that it’s important not to sensationalise something so as to dehumanise the subjects or expose them to harm from a misunderstanding public.

RN: How can up-and-coming fashion journalists in South Africa strike a balance between celebrating countercultural expressions and critiquing problematic aspects within these movements?

KM: That’s another difficult one. I guess it goes back to your purpose and mission as a writer and who you’re writing to/for. Consider what’s actually valuable and beneficial to improving circumstances versus what is entirely beneficial to your reach and impressions.

RN: Do you believe that counterculture will continue to be a driving force in fashion journalism in the coming years? If so, how do you envision its role evolving and how can we keep up with its coverage?

KM: That’s hard to say because I don’t know if counterculture still exists in the way we’ve always understood it. I think the path forward will be wading through the never-ending emergence of new movements and perspectives and deciphering what’s actually indicative of the zeitgeist, moment and mood versus what it is just a person on TikTok making a new hashtag to go viral.

One thing is clear – The future of counterculture in South Africa remains uncertain, as new movements and perspectives constantly emerge, requiring careful discernment amidst the noise of social media trends- Writers must consider their purpose and audience, focusing on what genuinely benefits society rather than seeking reach and impressions. We should be encouraged to approach counterculture with care, allowing insiders to speak and avoiding sensationalism. Countercultural figures, often outside traditional media, are reshaping authorities on taste and culture, the onus is on us to ensure equal representation of all.

Image courtesy of Afripedia by Andile Buka