“The quality of being is what soul is, or what a soul is. What is the quality of your being?”

This is the question Amiri Baraka puts before us in 1966, in The Burton Greene Affair. If we are to read his essay skeptically (as we should read the Liberal turned Black Nationalist turned Marxist critic), then you’ll find in his lacerating critique of white musicianship that soul — that, that quality of being — whatever it may be; is quite a Black thing. Although the rest of his essay proceeds to tell us that soul is that elusive and indivisible element of the black aesthetic, we are left all the more wondering what it, the soul and the Black aesthetic really are? Julian Mayfield offers us a feeling at best, perhaps as indivisible as Baraka’s “soul” in You Touch My Black Aesthetic and I’ll Touch Yours. He writes “I know deep down in my guts what it ( the black aesthetic) means…black aesthetic is easier to define in the negative. I know quite definitely what black Aesthetic is not.”

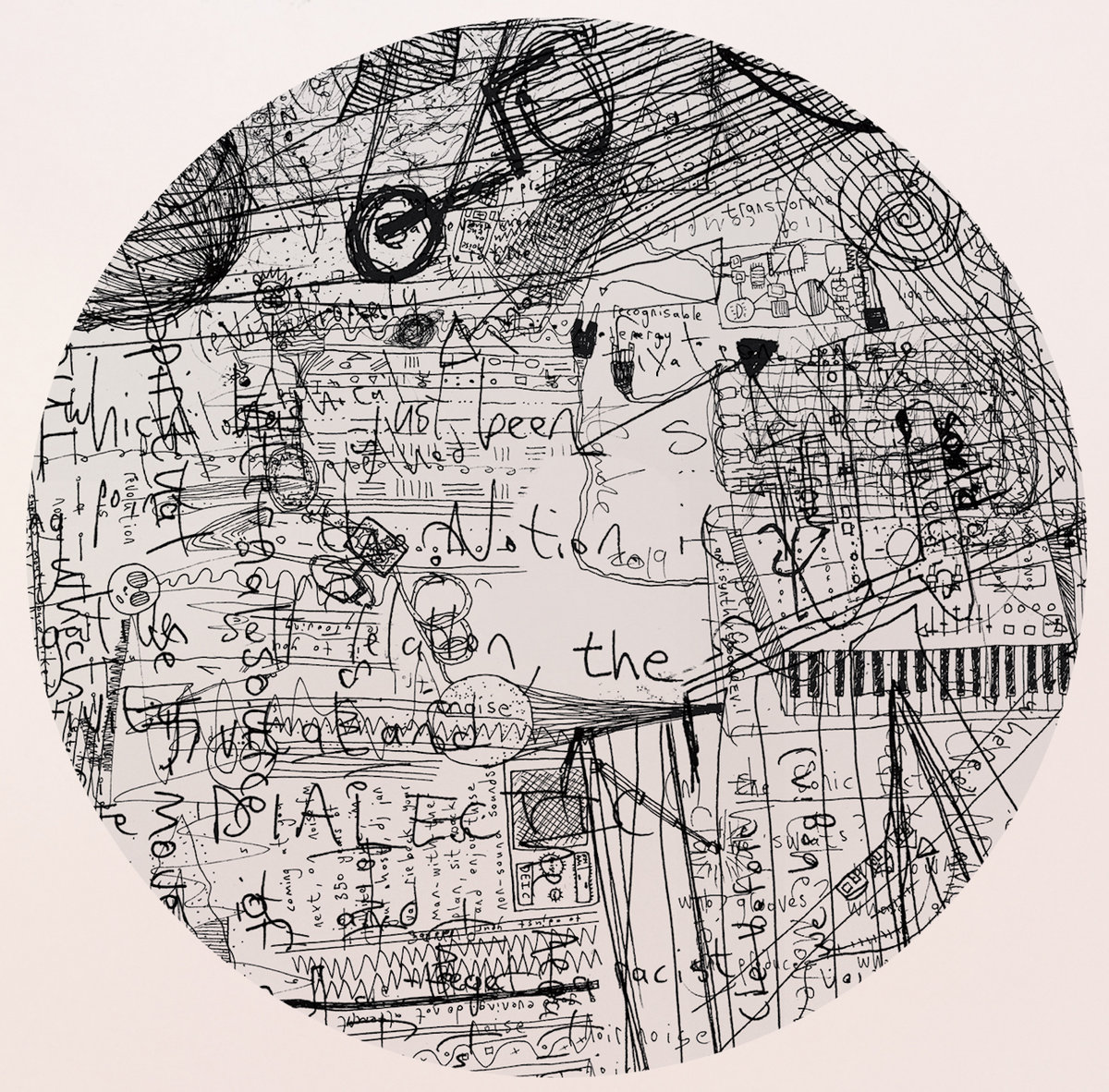

In Asher Gamedze’s debut Album Dialectic Soul, there is an attempt to provide us with an answer in the affirmative. Beginning with (I) Thesis, Asher gestures always towards disclosing the metric undergirding soul, the “unit structures” if you will, that make up Mayfield’s gut feeling. For Asher, however, unlike Baraka and Mayfield – soul is not simply an aesthetic category. The manner in which we divine the soul, the way we arrive suddenly at its feeling, the very aesthetic field which delineates judgment, merit and “feeling” is of historical matter too. To understand the soul then, we must study the history which produces it as aesthetical. It is in this history that Asher begins his reconstruction of Black music, working each arrangement outside of the predictable classicism which has come to characterise contemporary South African jazz. Here, he retrieves an avant-garde whose terms of experimentation are revealed through the course of the album to be an actual metaphysics. He elaborates for instance, what the great free jazz drummers before him initiated, what Christopher Meeder naively calls “the abandoning of time”. And like his predecessors he shows that the technicity in lost time has nothing to do with convention and everything to do with what Oyewumi Oyeronke calls a “world sense”.

The West’s hegemony over aesthetic structures has meant that the “abandoning of time” or the “losing of time” have become commonsensible classifications of metre signature. But it is precisely these classifications, the cultural-logic of time as we know it which Asher abandons. There is no abandoning of time, losing of time nor at any point any keeping of time taking place. For Asher, time as a universal aesthetic grammar must be emptied of its temporal, linguistic and symbolic congruence. What is instructive in his configuration of narrative and composition is not that time is absent but that it is always present, happening. As Frank Wilderson reminds us, “if time is an ocean, rather than linear (as white cultural imperialism defines it), then 500 years is simultaneously this minute.” At 54 minutes, Asher’s debut album attempts to dispose of this linearity by charting a musical cosmography of the Black Radical Tradition. Beginning with the triptych “State of Emergence”, he parses an odyssey together through centuries of resistance and it is here — between scenes of insurrection and defeat — in the interstices of memory, where there is “Hope in Azania” that we find the dialectic that constitutes soul – improvisation.

photograph by Elijah Ndoumbé

Like Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism, Asher’s album bears similar irony in its title. His Master’s Thesis titled “It’s in the out sides: An investigation into the cosmological contexts of South African jazz”, reveals that this is not merely coincidental. Following Robinson, Asher attempts to reveal a dialectic that contradicts the materialist fundamentalism of the West. In Dialectic Soul, he foregrounds improvisation as a distinct organising principle in his ensemble and as the ensemble’s representative and symbolic equivalent in Africa. For at the centre of the historical processes which have come to produce the political and social relations of blacks is the cultural basis of resistance. Drawing on Malombo, Marabi and Goema among others, he traces the lineage between American Jazz traditions and their African forebears. Asher never once departs from this cultural order, suggesting that improvisation and the search for liberation are coterminous; that if one speaks of improvisation without liberation, one merely describes a stylistic invention that bears no distinct relationship to Africa.

It is well documented that Bach, Mozart, Handel and others of their generation were “great” improvisers but the basis of their improvisation was founded in the aesthetic regimes of the West; an ordering of music which constrained the range of movement, facility and expression to the privileging of the empirical world and the effect of this musico- philosophy is that race and its corresponding technologies in slavery and colonialism were reinforced through the inauguration of this music to the status of classical. Dialectic Souls tells us that not all music is free and more pointedly that not all jazz is free. What makes free jazz “free” is the intractability of improvisation from liberation, and the knowledge that how one interprets the world shapes the manner in which it is accounted for. Though Free Jazz may describe composition or style, it is really about an attitude of resistance, the posture of liberation – the composition of the soul. Asher reveals that improvisation is the aesthetic instantiation of this posture. This is to say that improvisation is a constitutive element of Black life and that even though resistance may rise to the level of the spectacular, it is also very much quotidian – why improvisation as demonstrated in Dialectic Soul, is the anatomy of Black music.

The current milieu of jazz talent ought to be disoriented by the album’s statement. One would have hoped that the discursive conditions introduced by the “post” 94 moment would have enlivened the critical aspirations of jazz musicians today. Yet, the contemporary moment has been contrived by most South African Jazz musicians through a succession of redemptive odes; fictive representations of Black life concealed in melodrama and too much repetition. A kind of democratising of Jazz if you will, that extolls collaboration over cultural sovereignty. To be frank, Jazz today in South Africa is filled with too much talent and very little intellection. However, Gamedze makes sure not only to exhibit his knowledge of our past but he also wills it into a glossary for musical ideas. This is a concentrated study in method, a “refusal of closure” as Fred Moten puts it; that begins with a genealogy of Black music and in the fashion of the Black Radical Tradition critically ends with a new preface. Not only does he disclose the history of which he belongs to, but he leaves with us – his kinfolk, an artefact from the recesses of our past. It is an ambitious piece of work and rightfully so, should be greeted with the requisite doubt it deserves, for high praises have all too often been the distinguishing feature of mediocrity.

“Radical” in the case of Dialectic Soul is the most neutral term to call the album.