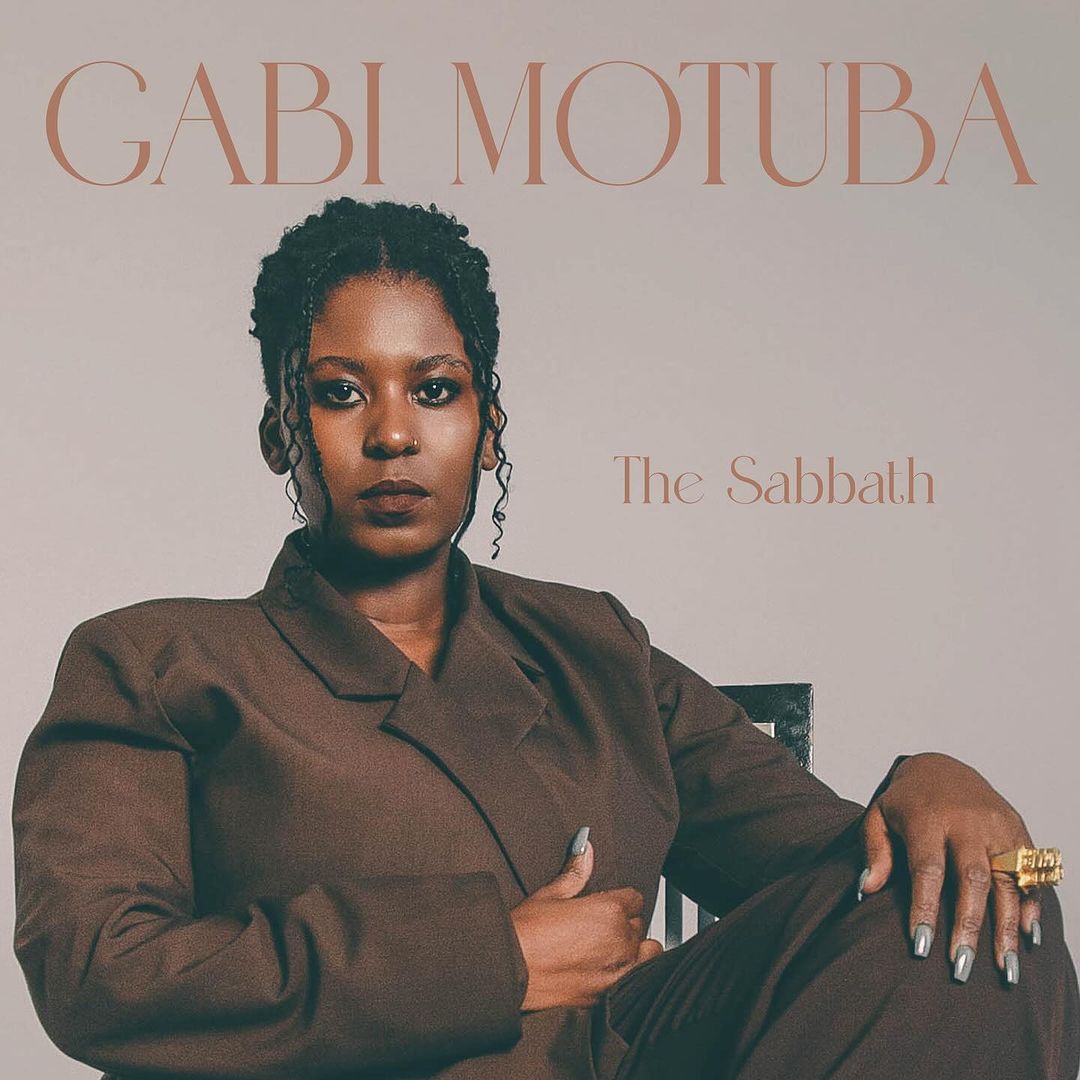

The award-winning vocalist, composer, and arranger, Gabi Motuba, has a unique presence in South African jazz, but even as I met her for a cuppa at 44 Stanley’s Black-owned St Germain, I got a familiar feel for her famed calming and graceful demeanour. With a career spanning over a decade, her latest project, The Sabbath, marks a simultaneously new and ongoing chapter in her sonic odyssey. We discussed everything from education to community and her thoughts on the interplay of spirituality and theory in her music.

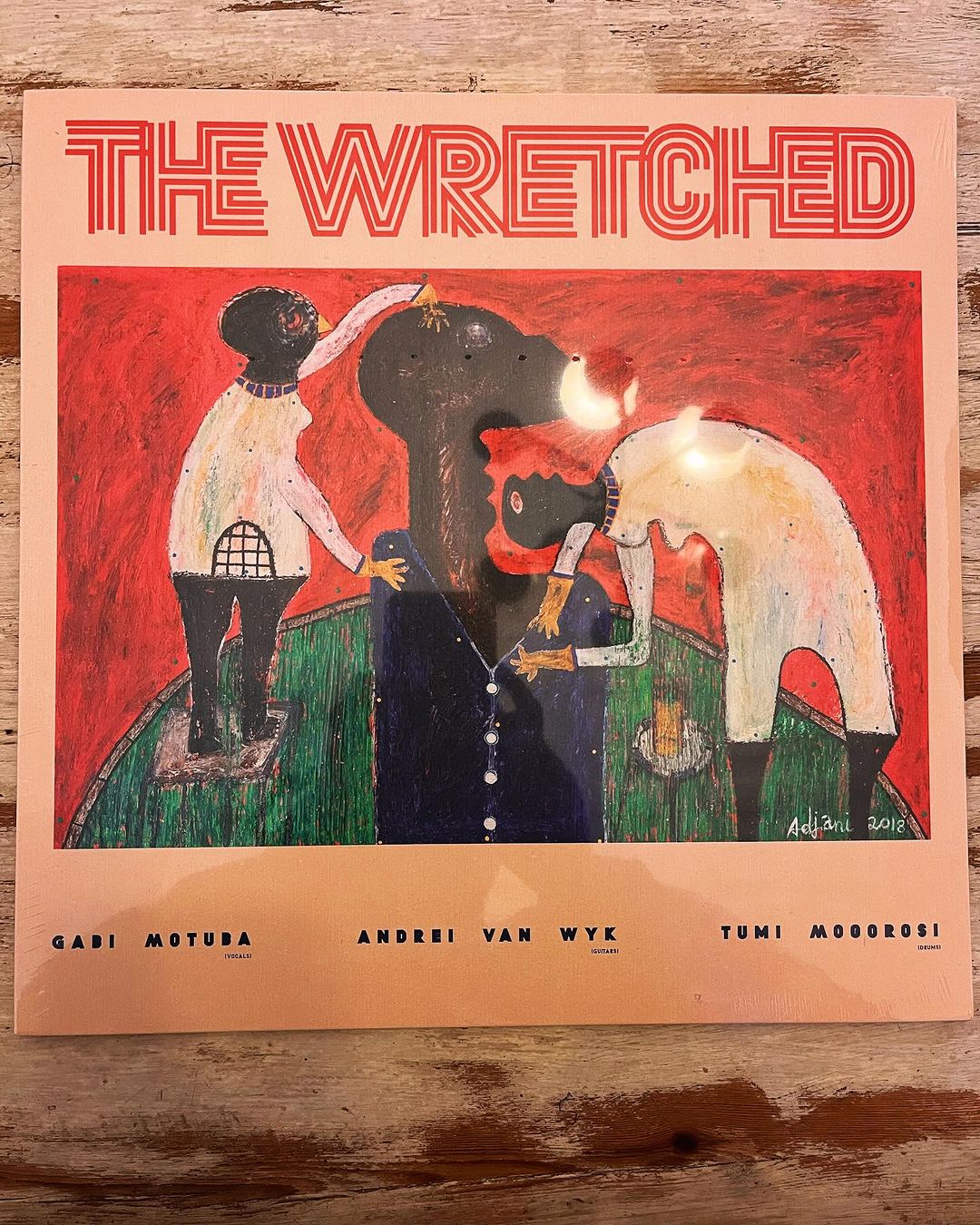

Motuba earned her bachelor’s degree in jazz studies from Tshwane University of Technology (TUT). Her discography includes the duo album Sanctum Sanctorium (2015) with Swiss pianist Malcolm Braff, her debut album, Tefiti-Goddess of Creation (2018) and The Wretched (2020), a project inspired by Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961) made in collaboration with Tumi Mogorosi and Andrei van Wyk.

There is a sense of oneness in the way the artist approaches her musical practice. One of the things we lingered on the most during our chat was the notion of a “sound life” as Motuba puts it. “I’ve always loved music from the very beginning,” she recalls. “I remember in grade one even, like when I was seven years old, I was in this recorder arts school program. So I took that very seriously. Like I used to practice like crazy.”

“So you didn’t change much,” I interjected.

“I didn’t. […] And ever since then, I haven’t looked back. Like, I was in primary school choirs. […] I went deliberately to a high school that had a music program. So my family, my parents kind of saw it already and were just like, are you sure? And I kept saying, yes, yes, yes. And then I eventually ended up at TUT.”

“I’ve heard that your class at TUT was filled with influential people,” I offered fishing for fervid detail. Motuba spoke with the utmost respect of being immersed in a community of peers including Tumi Mogorosi, Sibusile Xaba, Nhlanhla Radebe and Nhlanhla Mahlangu whose engagement with music went beyond mere instrumental skills. “But I guess this is also what higher institutions give to you. […] So when you’re there, you kind of are opened up to like the sound world. […] Sound and academia. Sound and film. Sound and history. […] Sound and archive. Yeah. So that’s where I found all these different, I guess, expressions of music.”

I went on to ask about the role of spirituality in Motuba’s music. “I think it’s just something I feel, you know, it’s just something that I’m informed by a lot, […] from my family […] being from a grandmother who was like known as like a prayer warrior […] in the community […] my father’s side […] there was also this very big spiritual presence […] culturally and religiously. […] It’s just something that has always been part of my experience, my lived experience.

So […] it’s not separate from me, but it seems as though when I do access music, I become a little bit more brave in terms of […] That part of myself […] subconsciously […] I try to think about it in a more theoretical way […] to kind of make sense of it, not to leave it in the clouds, but to […] root it within my practice, actively […] with titles like “The Law of First Mention” and “The Sabbath” […] So there’s always this dance between theory and religion, theory and biblical […] referencing that […] is a source of inspiration for me.”

Listening to Motuba speak of spirituality amplifies the interconnectedness of her inspiringly nuanced process. “I focus on the present to make my daily bread but I’m more interested in where we going. Right. And putting time also into this, um, multi kind of negotiated experiential place that I think that we’re on the brink of, ” she says.

I’m fascinated by this notion of “we” and as collaboration is a cornerstone of Motuba’s practice, I ask what it means to her. Her response gives away a mixture of respect for the input and influences of her collaborators and band members and a recognition that composition often begins long before the music is written.

“As a creative, I see this resonant […] in how I […] am forced to become the star. You know what I mean? How I can’t negotiate these spaces and I think the theory helps me to see that this is the world that we live in now […] I also think of myself sometimes in this front, forward, this individual, you know? So even when I think of myself as a composer […] what I need to be thinking is that other people are contributing to this body of work. But the problem is that there’s no structure that helps this kind of thought,” she muses.

As I listened, tickled by the profundity of her responses, I had the intense realisation of how intently the artist was listening right back. When pushed on this, Motuba pointed out that while the ethos of improvisation—listening and responding to others—exists universally in jazz, it has a different resonance in SA. “[…] when I’m in other countries, it’s not […] pronounced. […] It’s quite hegemonic. […] and it feels very forced. […] More technical […] these are the rules […] it’s like a flex. More than anything. But here […] It’s something that you want to do […] you’re just like […] can I please sit by your feet […] in a very organic way.”

Still on the topic of collaboration and its geographic specificity, we meandered onto Motuba’s residency at the Goethe-Institut, where she explored the concept of the “violence of care.” Inspired by Toni Morrison’s Sula (1973) and collaborating with Coila Enderstein, Motuba examined how care can sometimes be imposed in ways that don’t align with the needs or desires of the recipients. “I was interested in how care can be both nurturing and violent, particularly within the context of Black lives where the preconditions for care often don’t exist.”

I commented on how cerebral her work was and she responded, “The people who truly understand my work are few, as it requires a lived experience and deep engagement with these concepts.” This is what I appreciate about Motuba’s “sound life”—not only has it built communities prioritising shared nuance over broad acceptance, but it also addresses the challenges of navigating established structures. It doesn’t turn away. As we wrap up, Motuba asserts, “I don’t like rules; I’m allergic to them,” reaffirming her resistance in a world full of fear.

Motuba’s work, informed by Black radical traditions is a gentle reminder of a sonic proposal for creating worlds beyond white hegemony. Influenced by Saidiya Hartman and Afro-pessimism, Motuba’s is a localised concept of care with an ear for new structures and principles being built for the benefit of Black folk. Opening space for these kinds of discussions in the realm of jazz is both bold and bizarre—but a perfect blend for the active restructuring of how we live and (un)learn.

The University of Johannesburg (UJ) Arts & Culture will host the UJ Weekend of Jazz from August 29-31, 2024, at the UJ Art Centre, where Gabi Motuba will perform and launch her new album, The Sabbath (2024), on the opening night.