Which stories would I highlight – the underground anecdotes and thrillers; the days and nights of love and war; the weapons I carried (a Makarov in my shoulder bag in Gaborone, the AK next to my bed in Lusaka) – “a gun in trained hands is knowledge, its hinges and oily places as intimate as a lover…”

– Patrick FitzGerald in email correspondence

Epitaphs and Dreams, Poems to Remember the Struggle, by Patrick FitzGerald, was written for the most part, while the author was in exile. A collection of poems that express the inner workings of his mind at the time, they are raw with passion, thought, emotion, longing and liberation. The poems are broken up into chapters that intersect personal thematics such as romance and longing, with themes of struggle to paying tribute to comrades lost in battle. Loss and longing bleeds from the pages as he poignantly shares his truth; of those he has lost and those he cannot be with during exile. In this way it becomes a glaring reminder of the individual within a collective movement. Reflecting on the immense adversity of the struggle, these poems speak to a time that was less avaricious than our own.

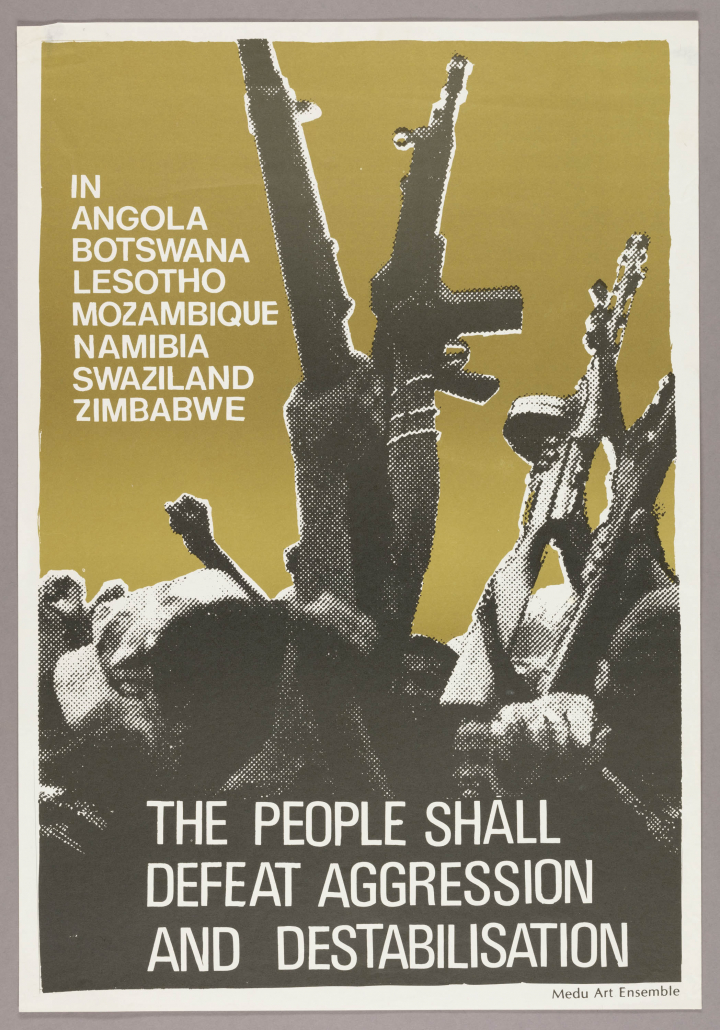

Poster by MEDU ART Ensemble, Thamsanqa Mnyele & Judy A. Seidman “The People Shall Defeat Aggression”; 1983.

“At the time, they were simply an expression of life in the struggle – or maybe, at times, just expressions of the struggle of life,” explains FitzGerald. He continues, “this time they were very consciously deployed, again for a political purpose – to save the concept of the struggle from being seen as either some sanitized super-heroic thing we must all bow down to semi-religiously, and from the opposite impression that it was simply a struggle of self-seeking scoundrels…”

FitzGerald was the Vice-President of the Wits SRC in 1976. “[We] put on quite a good show marching through Joburg on June 17th, only to be violently attacked by the plainly clothed police officers and the drug squad on Queen Elizabeth Bridge (all the uniformed and public order police were already busy in Soweto). Some of us fought back and were arrested and I was later charged with all kinds of crimes such as assaulting a policeman.” In 1977, FitzGerald was the Secretary General of NUSAS, an organisation with a proud anti-apartheid tradition. In the same year, he was detained whilst preparing for the one-year commemoration of June 16, 1976. He describes this experience to me as “theatrical”, as a conglomerate of security police officials tried to break his spirit. “I also fought back intellectually challenging their assumptions and tropes and likewise trying to mess with their minds…” In April of 1979 FitzGerald fled to Botswana where he would be for the next 5 years of his life. He was uprooted from there when his name appeared on a list of 17 “terrorists” handed over to the Botswana government by Pik Botha. Ordered by the ANC to retreat to Lusaka, this move, he believes saved his life, escaping the Gaborone Raid of 1995. “This brought about a transition from being a militant political activist on the frontline… to an ANC civil servant.” Later he was appointed as the Administrative Secretary of the newly established ANC Department of Arts, Culture and Sport.

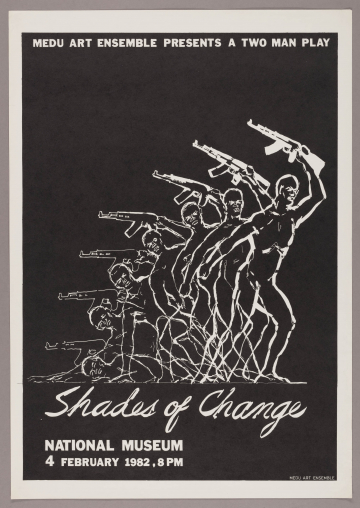

Poster by: MEDU ART Ensemble.

“We lived in the ‘welfare state’ of the ANC-in-exile which provided housing, food supplies, medical services, second-hand clothes, etc… However, as I always tell people, exile is not like jail. In some ways, one is restricted but actually life goes on…” MEDU ART Ensemble was an ANC-led organization fronted by dignitaries such as Thami Mnyele and Wally Serote, and was already established before FitzGerald arrived in Botswana. Aimed at being a voice in the anti-apartheid struggle through cultural intervention, FitzGerald became a part of the group and later served as Vice-Chair. “MEDU definitely functioned to keep me alive as a working poet,” he shares.

There was little to do in exile, with terrible television channels and endless coverage of the president broadcasted, FitzGerald turned toward one of the few enjoyments that incarceration held–a typewriter. The poems curated in this volume were meant for publication and some found their way into a well circulated journal of the 1980s by the name of Staffrider. He expresses the feeling of seeing his poems published in South Africa by saying, “… [it was] like a real mini-victory over the apartheid state and censorship system!” And to the beckoning question of why he wrote these poems, the Prof tells me, “I also wrote because the poems appeared in my head, heart and hands, and in some way, I believed I was documenting those times – to keep the memory of those times and places… I did not see myself primarily as a writer or artist – rather as a professional revolutionary.”

Poster by: MEDU ART Ensemble, Sergio Albio Gonzales “Shades of Change”; 1982.

The personal is political. The self cannot be removed from political ideology. This becomes even more apparent in poems that deal with romance and kinship relations. “…the person in the struggle is still the same person who continues to love and long and live. In some of the poems I deliberately join the politics to the love and longing – as I say in my intro when you are fighting in a revolution and are ready to die any day other emotions and passions seem to be heightened and more savoured…”

A focus on the individual emerges from the pages. Individual agency, or as FitzGerald explains, “the struggle was pursued by real people, not by mystical warriors, unambiguous heroes, or sanitized moralistic activists. In fact, very often my comrades were not only human, but all too human…” For My Son Justin Christopher, reminds of the individual, with his pains, emotions and longing. A poem which “seeks to cauterize this wound in some way”.

A famous poet, writing about an even more famous poet, states that ‘poetry makes nothing happen’, rather ‘it survives in the valley of its saying where executives would never want to tamper’.

– Patrick FitzGerald, Epitaphs and Dreams (Introduction)

* Prof Patrick FitzGerald is the Executive Director for Special Projects at Sol Plaatje University.