Big tech’s impact on society is more pronounced than ever and it is said to be successful because it works. Whether it solves industrial, logistical, or biomedical problems, on the surface digital technology is sold as generally good for the future of humanity. To some extent, it is even linked to freedom and prosperity, but the real-life political implications of tech are often overlooked.

For better or worse, the EFF national shutdown on Monday, 20 March 2023 made headlines around the world. With so many people able to experience the event in high resolution on their devices, Bubblegum Club uses Monde Gumede’s artwork Forwarded Many Times to discern the thrill and the threat of having such political intrigue at our fingertips.

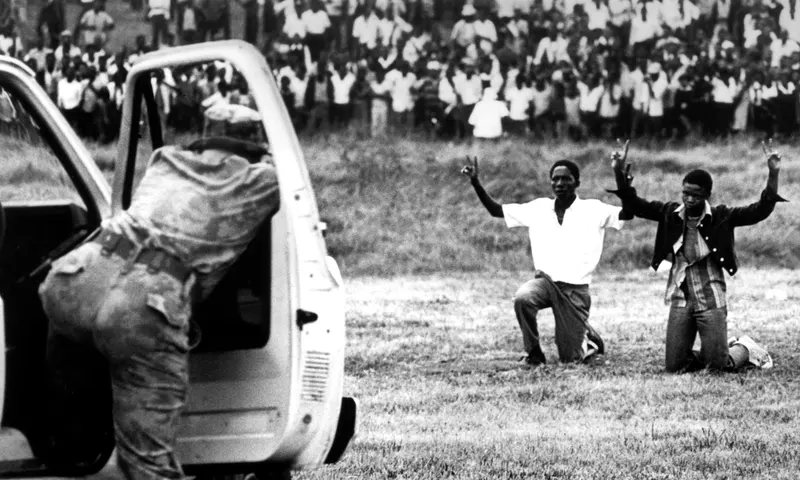

Image: video still courtesy of Economic Freedom Fighters

Violence is Not a Vacuum

It’s no secret that South Africa’s brush with violence has lingered. This country’s history is marred by a remarkable amount of violence. Following the colonial period and occurring between 1948 and the early 1990s, apartheid was a system of institutionalized racial segregation that the country has found particularly hard to shake. In the apartheid era, the South African government enforced discriminatory laws against the black majority. Because of its challenge to white minority rule, opposition to apartheid was met with brutal violence.

The 1960 Sharpeville Massacre and the 1976 Soweto Uprising are some examples of this justification being used to demonize, violate, and murder black folk. Even as apartheid came to an end during the late 1980s and early 1990s violence erupted between various anti-apartheid groups, particularly the African National Congress (ANC) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).

Though the end of apartheid did little to quell South Africa’s high levels of violence, after 1994, young South Africans did have a brief reprieve under the contentious banners of the Rainbow Nation or the Born Free Generation. But recent events like the COVID-19 pandemic, the #blacklivesmatter and #metoo movements, the Ukraine war, the Eskom fiasco, the National State of Disaster, and now the National Shutdown have harassed the unhealed wounds of the continued subjugation of black folk through tech.

Proponents of technology will be quick to rush to its defence, but let it be known that Bubblegum Club loves technology. We’re fascinated by how the Facebook Rapist Thabo Bester’s escape was uncovered via Twitter, proving that digital technology is a useful tool in today’s society. It is precisely because of our passionate preoccupation with tech and its dance with time that we choose to observe it for what it is. Technology is alive. It is our reflection. It does not exist in a vacuum and nor do we.

Photograph: Foto24/Getty Images

A History of Violence

History has repeatedly revealed that technology and violence are intricately intertwined. Like anything, the advancement of technology can be used for good or evil. Whether it be swords, guns, bombs, or drones, the development of weapons is an obvious example of how humans have used technology to produce violence. But some examples of the link between technology and violence are more obscure.

This is particularly true in the history and evolution of the Internet, which despite its benevolent facade, is plagued with instances of seemingly inadvertent violence. The Internet operates as a vast network of interconnected computers that send messages to one another through data packets. This may appear as a purely mechanical or mathematical process, but time reveals that this process is also political.

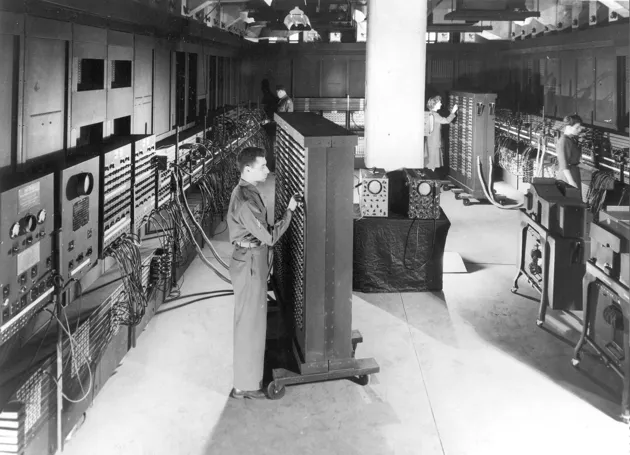

While the Internet was not developed until several decades later, some of the earliest attempts to make computers do what they do were during World War II. Machines like the American ENIAC and the British Bombe were used to decipher coded enemy messages and gain critical intelligence. Early computer technology was also used to calculate the course of munitions such as artillery shells, which improved the accuracy of an attack.

The development of computer technology during and after World War II laid the foundation for what we know as the Internet. These early advancements are what allowed researchers and engineers to explore novel ways of connecting and sharing information between locations. This resulted in what we know as the digital revolution and while it has been a stunning cultural phenomenon, even its most optimistic observer would find it hard to omit the Internet’s inevitable contribution to the spread of violence and hateful attitudes.

Image courtesy of Unidentified U.S. Army photographer

Digital Danger

Despite its best intentions, the Internet is dystopian. Governments and corporations use it to monitor and control people’s behaviours. Facial recognition technology can identify and track individuals, often without their knowledge or consent. Hackers use technology to steal sensitive information or collapse targeted computer networks.

Social media platforms make it easy to spread hate speech, misinformation, and propaganda, which can contribute to political unrest. Filter bubbles and fake news shape societal belief systems. Extremists use the Internet to radicalize individuals, recruit new members, and inspire them to commit acts of violence.

The Internet has also made it increasingly easy to send menacing messages to others. Revenge porn can be cited as a digital form of sexual violence. It is now common knowledge that because of its dangerous capacity to spread like wildfire, cyberbullying can potentially have devastating effects on its victims, leading to job loss, alienation, depression, anxiety, and even suicide.

The case of Lufuno Mavhunga, a 15-year-old girl who committed suicide after being cyberbullied and physically assaulted on 12 April 2021 at Mbilwi High School in Limpopo, South Africa, demonstrates that digital violence can easily escalate or equate to real-world violence. What’s worse – the anonymity and distance associated with the Internet make it easier for perpetrators to bully and harass others without being held accountable.

Forwarded Many Times (2021) by Monde Gumede

Forwarded Many Times (2021) by Monde Gumede

Monde Gumede’s video Forwarded Many Times (2021) is an apt illuminator. It follows the long tradition of black South African visual artists like Santu Mofokeng, Zanele Muholi, and Mary Sibande who make political art. Yet its critique of the socio-political effect of digital media allows it to sit snugly in the niche between high art and lowbrow culture.

As a form of artistic expression Forwarded Many Times is unique in that it uses digital technology to explore and comment on the 2021 political unrest in South Africa, which is also referred to as the July 2021 riots or the 2021 Durban riots. Comprising mainly of screenshots, it encompasses a wide range of sources, including memes, digital chats, social media posts, images, voice notes, and videos. Because of its harrowing relevance, the video feels simultaneously interactive and liminal.

Forwarded Many Times is a satire of the political positioning and ideologies of contemporary South Africans. It spotlights the socio-economic inequalities that remain steadfast in this country and the subsequent violence exerted by both sides of the poverty line. It even goes as far as suggesting that digital technology was used to incite said protests and subsequent political violence. In this way, the old art world adage “form follows function” is particularly of use. Gumede forces digital technology to critique itself.

Photograph by Terrillo Walls

Afro Tech Futures

As Forwarded Many Times demonstrates, digital art is an ideal medium for the exploration and critique of the prominence of digital technology, but this critique does not have clear-cut connotations. The democratic, controversial, and often either perversely public or superficially anonymous nature of political digital art also makes it susceptible to regulation and censorship.

If governments or corporations view the work as a threat to their authority, artists can face additional violence to the violence they may be attempting to expose. This is significant because, given the historical subjugation of black people through technological instruments of power, one of the most pronounced threats to the future of black folk in tech is the role of corporate or government regulation.

It is true that regulation is necessary to ensure that digital technologies are safe, secure, and ethical, but overregulation can also stifle innovation. As global corporations and governments grapple with how to regulate emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and autonomous vehicles, we should be mindful of the sovereignty of digital artists and innovators who could propose counter-futures.

The social, political, and ethical implications surrounding emerging technologies are not only historically relevant but also impact the development of technological futures in Africa and her diaspora. As new technologies emerge and existing ones evolve, they bring with them new challenges and opportunities that require new solutions and perspectives. Digital futures should become a topic of growing interest and concern for previously subjugated peoples.

Gumede’s Forwarded Many Times ends with the caption: “The stories we tell shape our reality. Interrogate everything.” This call to action gives us a glimpse of just how inconceivably fast and vast the factors that shape our digital landscape can be. While this can come off as bleak, the artist’s aerial overview of South Africa’s violent past and vivid present in the context of digital technology also hints at the immenseness of potentially positive perspectives. An assertion that seeing darkness does not negate light.

One could argue that due to its environmental impact, there is no ethical way to engage with digital technology, but one could not deny that it can be used responsibly and generatively. Among a myriad of things, digital technology has provided a platform for artistic expression, innovation, activism, social change, and education. With its wistful windows of newness, Forwarded Many Times exemplifies the accessible alchemy of the wondrousness and the wickedness of the world wide web.

Photograph by Emmanuel Ikwuegbu