Watching the contemporary art scene evolve is a little bit like watching a sports game as a complete philistine with no knowledge of the rules. You can’t really tell who the star player is, you’re definitely not sure where the ball is going to go, you have no conception of what is allowed or not allowed, and just when you think you’ve gotten the grips of it, something unexpected happens and it is all upended.

As with so many fields, technology has infiltrated the contemporary art scene. So just as you thought you were beginning to understand the Tracey Emin’s, the Ai Wei Wei’s, the Nicholas Hlobo’s, the Nandipha Mntambo’s, the art world threw you a curve-ball in the shape of the algorithm.

Now I would like to think I am no novice when it comes to art but ask me about coding or Java or (I can’t even think of another word to put here) then I am stumped. As long as I can open my emails and post instastories then I don’t need to know. It is like that time old saying – “If you love something, don’t find out how it is made.” But now, the foreign language of programming is seeping into my perfect little contemporary art comfort zone, and I might need to start learning the rules.

So as every good writer and researcher in the 21st century does, I went straight to Google (Ironically using its complex algorithms). Google told me that an algorithm was a “set of rules, or a process used in calculations or other problem-solving operations.” I mean if I’m honest, this didn’t help me much. As a society that are more attached to our devices than perhaps could ever have been predicted. Something that has always resonated with me was the video produced in 2015 of Otis Johnson, who had been released from prison after 44 years of incarceration. In this short interview with Al Jazeera, he gets off the subway at Times Square and is immediately bewildered by what he first thought was everyone talking to themselves but turned out to be what we all know to be FaceTime. It was the first moment where I sat and really considered how detached from reality we really are.

Each step on a Fitbit, each 4am tweet, each calorie counted, or song downloaded is being controlled by that terrifyingly foreign language of code. Plebs like myself see 0s and 1s, and lots of disruptive / and ? and * and [ ] – yet the next generation contemporary artist is seeing infinite possibilities.

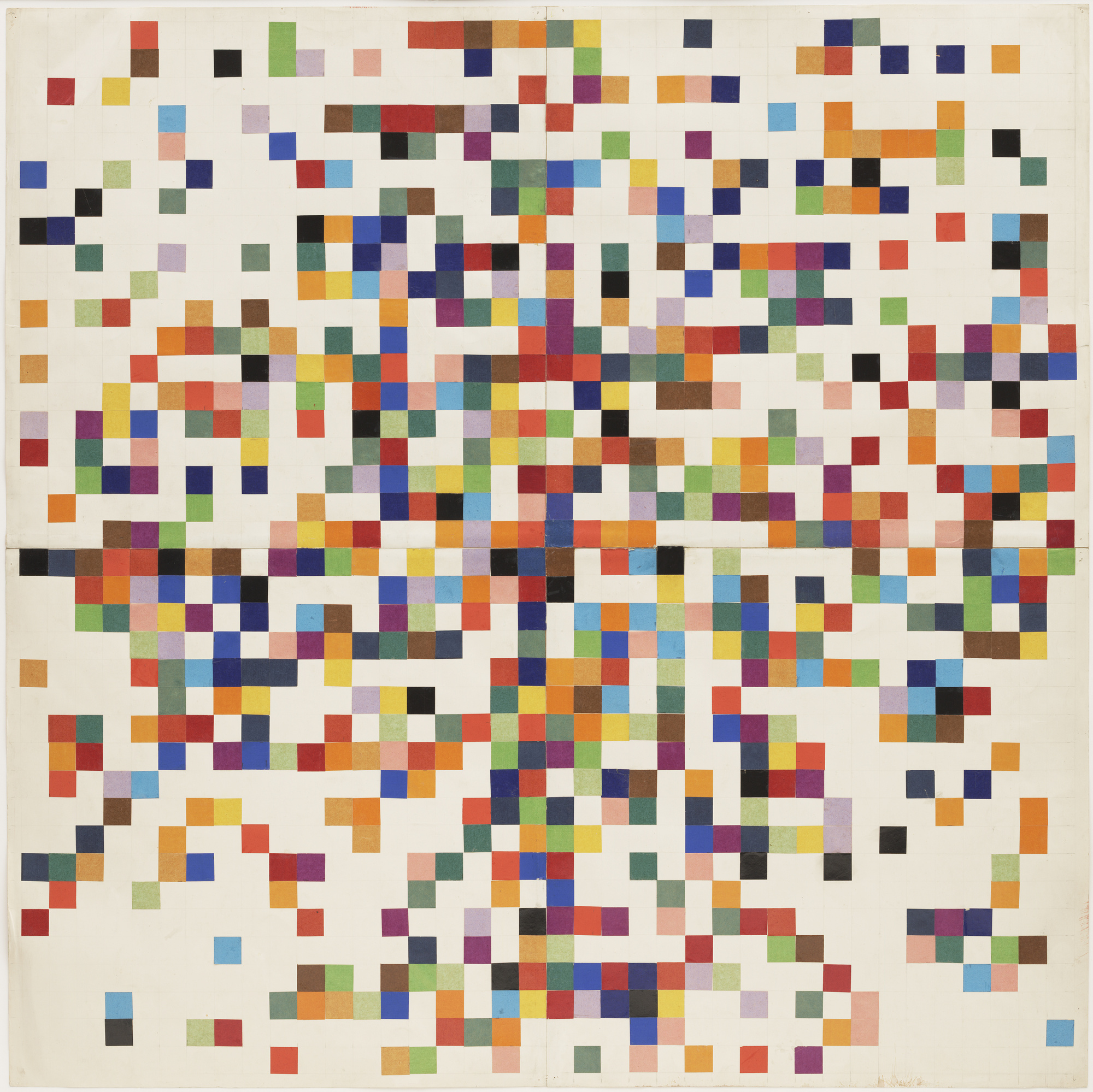

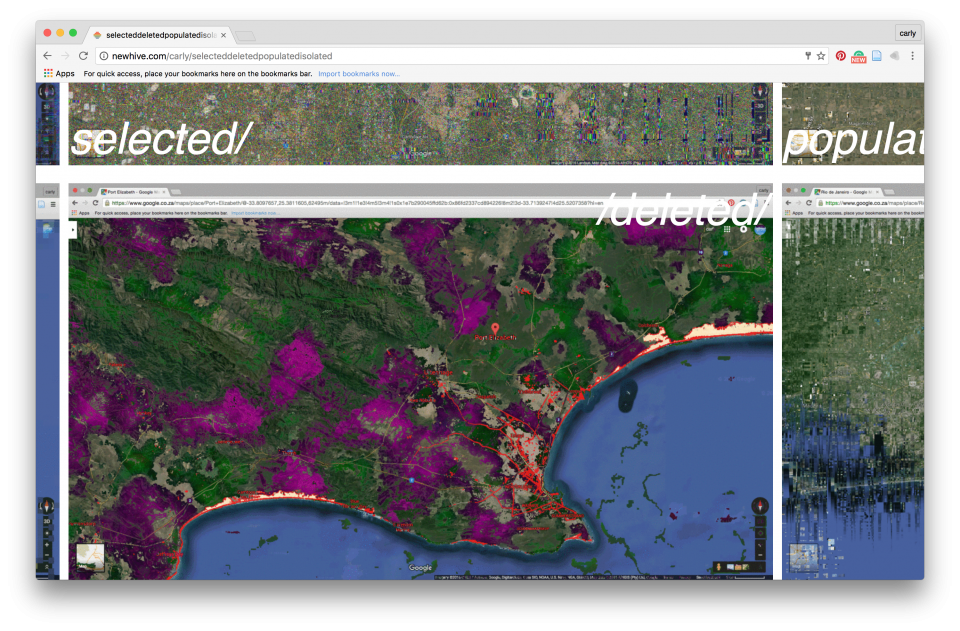

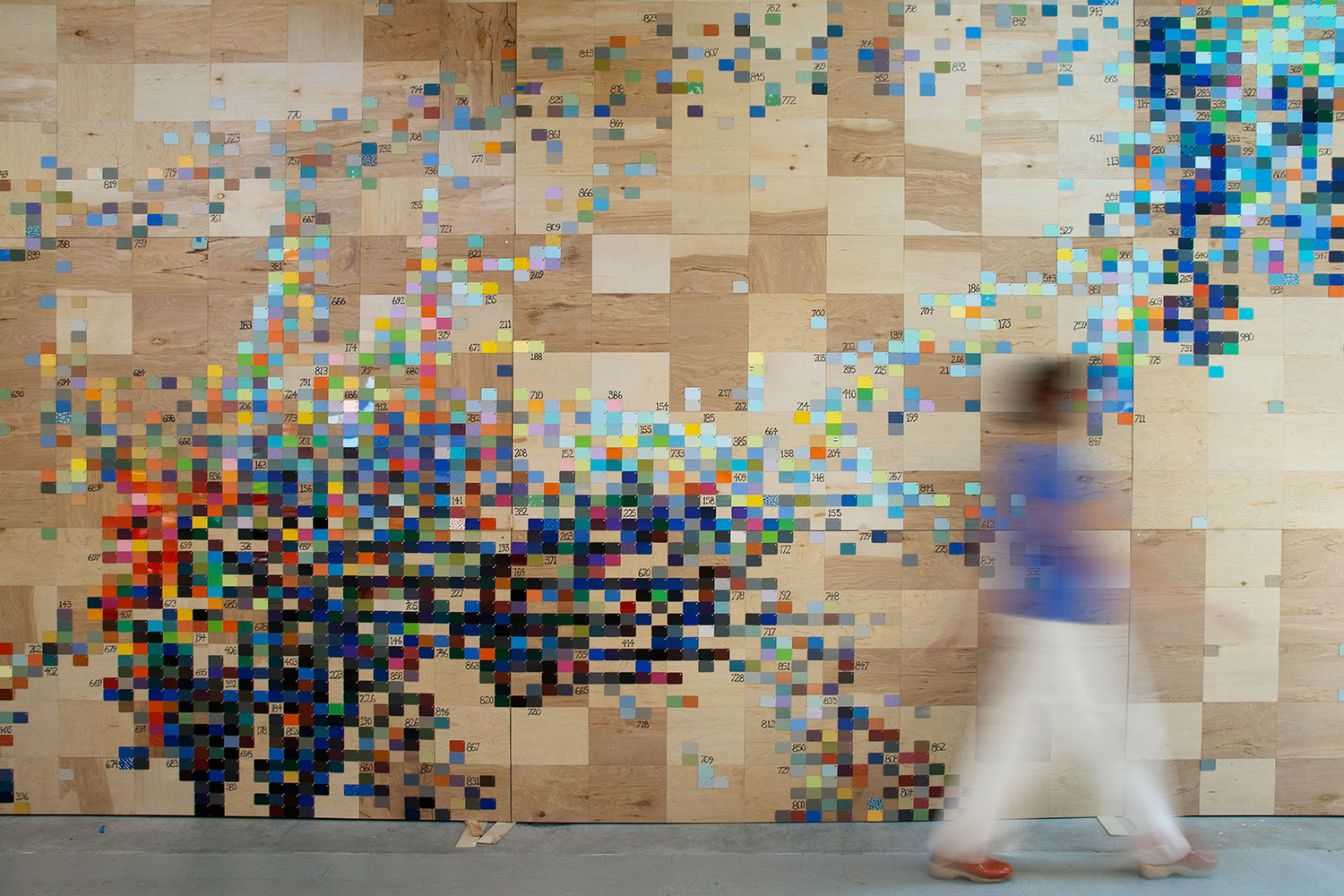

Take Laurie Frick, a New York based artist, who has used various data-trackers to create large-scale representations of ‘self.’ In 2012, using the app Moodjam, Frick tracked her emotions and moods over the course of several days and then created works like the one below as visual articulations of this data. At first glance we see work akin to the mid-century minimalists Sol LeWitt, or Ellsworth Kelly. Closer to home, Johannesburg’s Carly Whitaker’s Selected/Deleted/Populated/Isolated from 2016 uses collected, collated data to consider the representation of ‘other’ and uses Photoshop to disrupt and distort Google map images to create connections between cities in the global south. Each of these examples reflects on how digital data can lead to the abstraction or reorganisation of information.

And so, I ask, has the new artistic tech-evolution redefined the abstract?

Now that the digital age has permeated so much of our daily activity, how do we, as consumers of art, consider its permeation into the galleries? A large part of this new age of art seems to reflect on digital as disruptive. We see the background interfaces of the world wide web or distorted virtual realities – the relatively comfortable spaces of Google, Facebook and Instagram are discarded for the more uneasy abstract depths of the internet. Artists seem to be playing with the very ‘physicality of art’ – algorithms are used to create sketches that seem made of the human hand (See Jon McCormack’s Niche Constructions for example,or more fragmented abstract video works (like those of Casey Reas, or Diego Collado), or play with the developing technologies of virtual and augmented reality (See Blocked Content by the Russian collective Recycle Group or the work by Paul McCarthy and Christian Lemme.

While some of the Western world thinks we still ride elephants in South Africa, our digital artists are in their own way coming of age – spurred on by innovative spaces like the Centre for the Less Good Idea who had a Virtual Reality exhibition last year, and the annual Fak’ugesi festival that celebrates the rise of African digital innovation.

Two years ago, I went to the New Horizons exhibition presented by the CUSS group at the Stevenson, and left feeling bewildered. As one expects when they see life-size pixelated dog statues, couches floating in Dali-esque, virtual waters and photoshopped couples superimposed into neon-blue digitally rendered nightclubs that look like the infamous Avastar (may it RIP). Were they considering the banality of the internet, the superficiality and excess of capitalist culture, the absurdity of digital programmes like photoshop and the constructed ‘realities’ they create, or perhaps they were just commenting on society’s gluttonous consumption of the ‘digital dream.’

Part of what the age of the algorithm means is that the digital is inescapable. Even Home Affairs uses computers these days. And as artists begin to consider the complexities of this omnipresent and opaque technology, we as viewers need to be prepared to confront a new abstract.

Many contemporary South African artists are transcending the boundary of the screen or page and using 3D ‘collages’ to juxtapose the virtual with the corporeal. At the Post African Futures exhibition at the Goodman Gallery in 2015, Pamela Sunstrum and Thenjiwe Nkosi created a visual cacophony, Notes from the Ancients, and used installation to contrast the now all too familiar motherboard, with 3D printed masks mirrored on ‘traditional’ African artefacts, murals of mine-dump sand dunes, and defunct technology. This type of disruptive installation makes us constantly try to construct connections, to create some type of linear understanding. Frequently we are left dissatisfied, or with so many ideas spinning in our head we feel dizzy.

Tabita Rezaire’s Exotic Trade of 2017, also exhibited at the Goodman Gallery, considered the erasure of black womxn from the “dominant narrative of technological achievement” (Rezaire 2017) and how much of scientific advancement has capitalised from the ‘availability’ of the black body. The juxtaposition of images from African spirituality, the ‘glitchy’ virtual world, the jarring electric pink gynaecologist examination table, and the omnipotent, frequently ‘sexualised’ or ‘maternalised’ black womxn body are jarring reminders of the darker side of the digital arena. The motherboardby name reiterates the ‘mother earth’, maker of all – but disrupts the notion of the natural by the ubiquitous computer. We are confronted with a maze of imagery, that traverses the boundaries of the body, and technology itself.

As we begin to adjust to a new abstract, I ask – “where to from here?”