The KZNSA Gallery is opening its doors for the year with an impactful exhibition—Mating Birds Vol.2. The exhibition engages different materials—coalescing visual art, literature, philosophical texts and reference material to engage the effects of colonialism and apartheid laws (particularly the Immorality Act) on South African contemporary sexual relationships.

The show is expressed as a curatorial essay with Lewis Nkosi’s Mating Birds as a starting point.

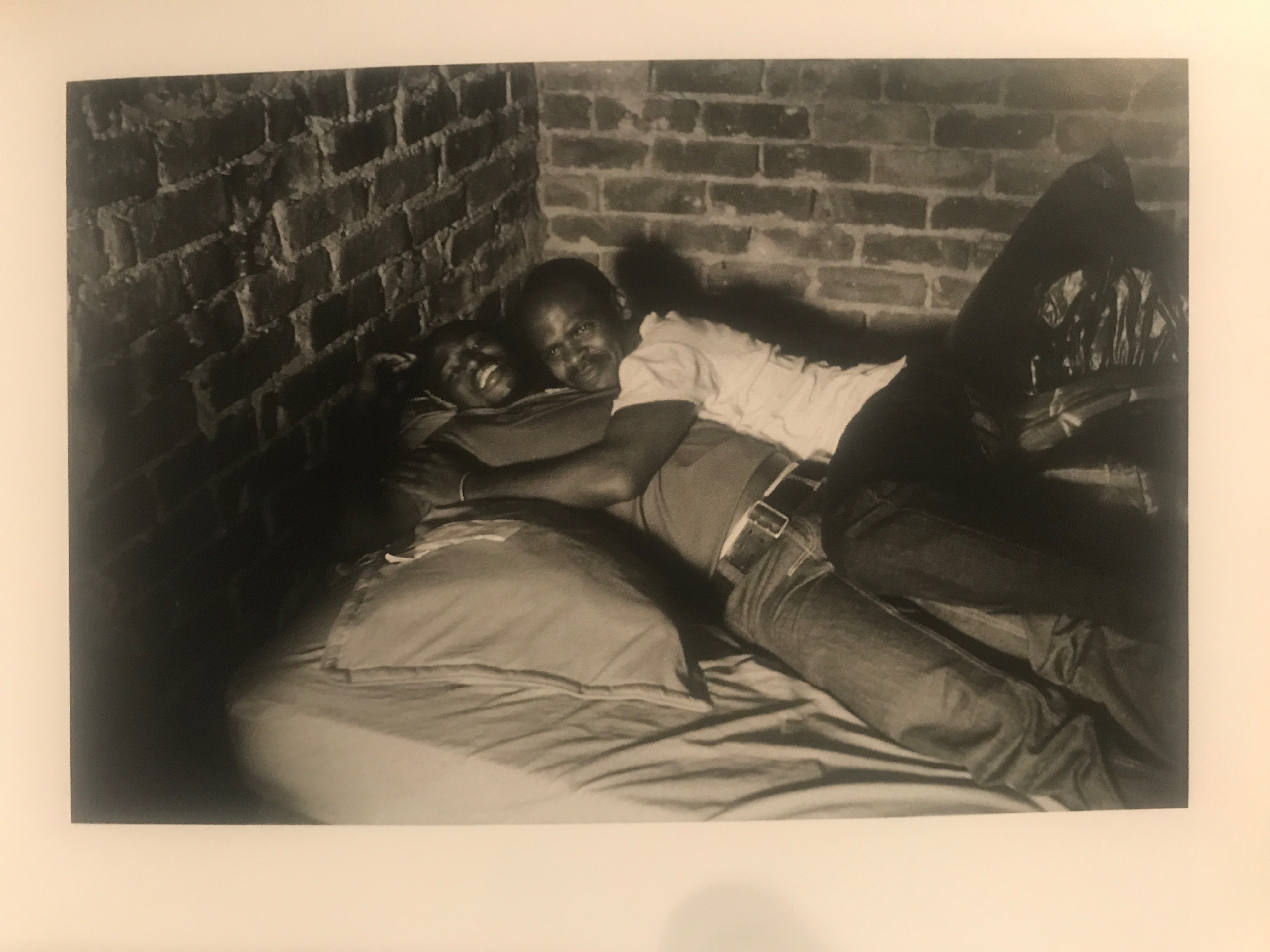

Mating Birds Vol.2 will take place until 10th February 2019 at KZNSA Gallery’s main, mezzanine and media galleries, featuring visual artists Billie Zangewa, Dineo Seshee Bopape, Lady Skollie, Sabelo Mlangeni, Simnikiwe Buhlungu, Tracey Rose and Trevor Makhoba—with reference materials drawn from Bessie Head, Lebo Mashile, Makhosazana Xaba and Zakes Mda.

I had an interview with the three curators; Gabi Ngcobo, Sumayya Menezes and Zinhle Khumalo.

I’m interested in the locality for this exhibition—are there factors that contributed to the exhibition being presented in KZN, specifically at this gallery?

GN: The curatorial essay takes its locality, eThekwini/Durban, as a starting point. It does so by activating a work of fiction also set in Durban, highlighting, among other things, how segregation by colour lines in the apartheid South African landscape comes to bare in our present; be it at the beach and other holiday destinations, cultural spaces such as galleries and museums, institutions of learning, etc. It is also important that Nkosi’s novel is set in Durban’s segregated beaches and that the curatorial essay at the KZNSA Gallery is the first project of 2019, coming directly after a holiday period for which Durban is a popular destination amongst local holiday takers. The essay therefore activates the spatial history of South Africa in order to highlight recent events that have informed the ocean space, the Penny Sparrow and the very recent Clifton Beach incidences resonating…

ZK: With the KZNSA Gallery being one of Durban’s leading exhibition spaces and for its current ethos of activation, incubation and transformation, it is quite fitting for the essay to locate itself within Durban. The essay also gives opportunity for Durban, as a community, to question and explore its own conservative perspectives on contemporary sexual and spatial politics in South Africa.

SM: The KZNSA was granted funding by the Department of Arts and Culture, enabling the society to invite curator Gabi Ngcobo to curate an exhibition in the space. From there, Durban as the location for the curatorial direction embarked on becomes significant – yes, it is the setting for the novel, and the birthplace and final resting place for the late Lewis Nkosi. But Durban as an ocean city is significant as, particularly over the festive season, there is increased public awareness and attention paid to who is using which beach, often in a negative light which takes us back to the years of segregated beaches and the now social constructs that still remain long after the legislation has changed.

Can you tell us a little bit about the concept of the exhibition as curatorial essay—how this positioning influences what the show is and what it can achieve?

GN: To frame Mating Birds Vol.2 as a curatorial essay is a desire on our end to exit the exhibitionary complex, in order to stretch the possibilities of what a gallery can be and do. We wanted to create a space where knowledge can be re-activated, shared and produced. We, of course, recognise that the KZNSA Gallery is a space designed for exhibiting art and that we ourselves work within the field of art. We have invited artists through their existing work as well as commissioned a site specific work to highlight this. We have also been inspired by the questions posed by the artists in order to allow references and footnotes that have shaped the artist’s practices to also occupy the gallery space. In this way, we hope, the curatorial essay does much more than what a regular exhibition can do; it activates questions, inspires discussions and makes us all personally responsible for creating frameworks that will shape more enabling future narratives.

ZK: Mating Birds Vol.2 also lends itself as an educational tool in highlighting a part of South Africa’s history that could so easily slide into the forgotten archive. It also allows the viewer to dissect historical information, accompanied by contemporary visual interpretations, in a new perspective. In light of the current South African socio-political climate, the content in the Mating Birds Vol.2 allows the viewer to analyse, interpret and contribute to current discourse from another perspective.

SM: This positioning opens the exhibition space into more than a space for viewing art – it becomes a space for research and learning, as we bring to the fore archival and reference materials that would perhaps not usually be found inside a contemporary gallery space. We’re able to reference artists, bringing them into the exhibition space, without necessarily presenting their artwork, for example Zanele Muholi‘s work is referenced and represented in the format of a footnote accompanied by texts, and not framed and mounted as exhibition pieces. Similarly, we’re able to include almost a ‘literature survey’, showcasing the books and texts that informed the direction the essay took in a tactile way, sitting beautifully in the space alongside the artworks, rather than just as footnotes in the curatorial statements accompanying the work. Mating Birds Vol.2 is where we arrived taking Mating Birds as the departure point – the scope for where ‘Vol.3’ will emerge becomes broader, with the curatorial essay lending itself to responses from visual artists, writers and researchers alike.

I’m interested in this idea of sexuality and intimate relationships in the context of violence – reflecting on South Africa as a very violent environment for women and children – before we add the layers of race and class.

GN: The layers of race and class have been there for hundreds of years. We can even argue that the construction of race and class are the reasons why we are caught up in this violent mess. The colonial projects made sure that the values for what we considered natural shifted until we cannot remember a time when violence was not part of our daily lives. Mating Birds Vol.2 highlights how this was done by regulating how intimate relationships are conducted, thus making the natural seem unnatural.

ZK: I believe that a well rounded understanding of the dynamics surrounding sex and violence cannot be achieved without first exploring the consequences and repercussions of hundreds of years of race, class and the systematic processes implemented to dehumanise certain groups of humanity. Mating Birds Vol.2 plays an integral part in a much larger conversation.

SM: In the novel, the protagonist himself is unsure at times if what he did was with or without consent. The social and political constructs surrounding him (it could never be consent, he was a black male and she was white and that was that) made even him doubt his own perceptions and memories, bringing him to anguish and turmoil – surely it must have been an act of violence, even if it was an act of sexual intimacy? Where is the line that separates, and whose line is it? The violence and aggression that have such a toxic, unflinching presence today are learned behaviours, they have roots deep in the narrative of violent and unnatural segregation and separation that was so normalised in our history – it almost had to become part of the collective subconscious.

This exhibition opens up a lot of questions regarding the interplay between intimacy and power; one could argue that all relationships will present different forms of power imbalances, this somehow seems more perverted when the power is institutionalised. How are you thinking around this relationship between intimacy and power?

GN: Indeed, these are some of the themes explored in the essay. There are references to Zanele Muholi’s Massa and Mina(h) (2008 -) photographic series in which she staged herself and others in roles of servitude where a kind of intimacy develops between a maid and the madam, as well as between a group of black maids and a white man. These are juxtaposed next to a 1970’s National scandal, fictionalised in Zakes Mda’s ‘Madonna of Excelsior’ and one which marked a small town Excelsior in the Free State, where a group of prominent white men and black women employed as maids were arrested and tried under the immorality act. Were these women violently coerced, was the sex transactional, and, in general, is intimacy between those deemed powerless and the powerful able to transform the power of power? These are the kinds of questions the essay aims to generate or activate.

ZK: The variety of archival and literature references in this essay, as well as visual artworks, also play a role in questioning the relations of power and intimacy. Specifically citing from the literature compiled, we see ways in how power was emulated and perceived by individuals from different sides of the fence of race. Particularly, between whites and people of colour. Sarah Gertrude Millin’s novel God’s Stepchildren (1924) highlights the authors shame of a white man’s intimate relations with the native. While Zake’s Mda’s ‘Madonna of Excelsior’ celebrates the protagonist, Niki’s resilience to survive in spite of a dire position within her society. Power is relative in these circumstances. And how power and intimacy is received could be varied by race and class.

SM: Yes, every relationship holds forms of power imbalances and this institutionalised power is sickeningly perverse. When the power imbalance is bigger than the sum of the parts that constitute the relationship, there is almost no chance that intimacy will prevail. Intimacy cannot flourish without trust and security, and in a situation where power is institutionalised and can’t be challenged, the arena will never allow for both parties to maintain an equal footing, one will always keep the upper hand.