From December 2, 2023, to February 2, 2024, STEVENSON Johannesburg hosts I Miss Myself the Most, a noteworthy group exhibition on memory by the promising curators Aza Mbovane and Mosa Molapo. The exhibition walkabout presented a unique opportunity to engage with the curators, artists and viewers present at the Parktown location. The intimate yet ample group that gathered around the curators were a snazzy and curious bunch, inquisitively interacting with both the talks and the art on show.

The first room is perhaps intentionally unassuming. Around Allyssa Herman’s work, there were talks of nostalgia and deja vu, the simplicity of which one scarcely had incentive to inspect. While Steven Cohen and Frida Orupabo’s photographic collage-esque works hold their own in the entrance space, their familiarity within the STEVENSON lexicon makes them easy to look at and perhaps by extension, overlook. In an exhibition on memory, this room is somewhat unmemorable. The show heats up in the threshold between the first and second rooms.

Though still leaning on the reliability of the photographic medium, Motlhoki Nono immediately makes a mark with The Weight of a Kiss (2023). The work is indeed quite weighty, whilst maintaining a mischievous sense of play. Through her reflective red-hued digital scan, the artist conjures intimacy with raw assertion, diverging from the played-out design-like collage pieces prevalent in the first room. With its small scale and unlikely wholeness, Nono’s visceral work wistfully wills the viewer into what instantly becomes a safer space.

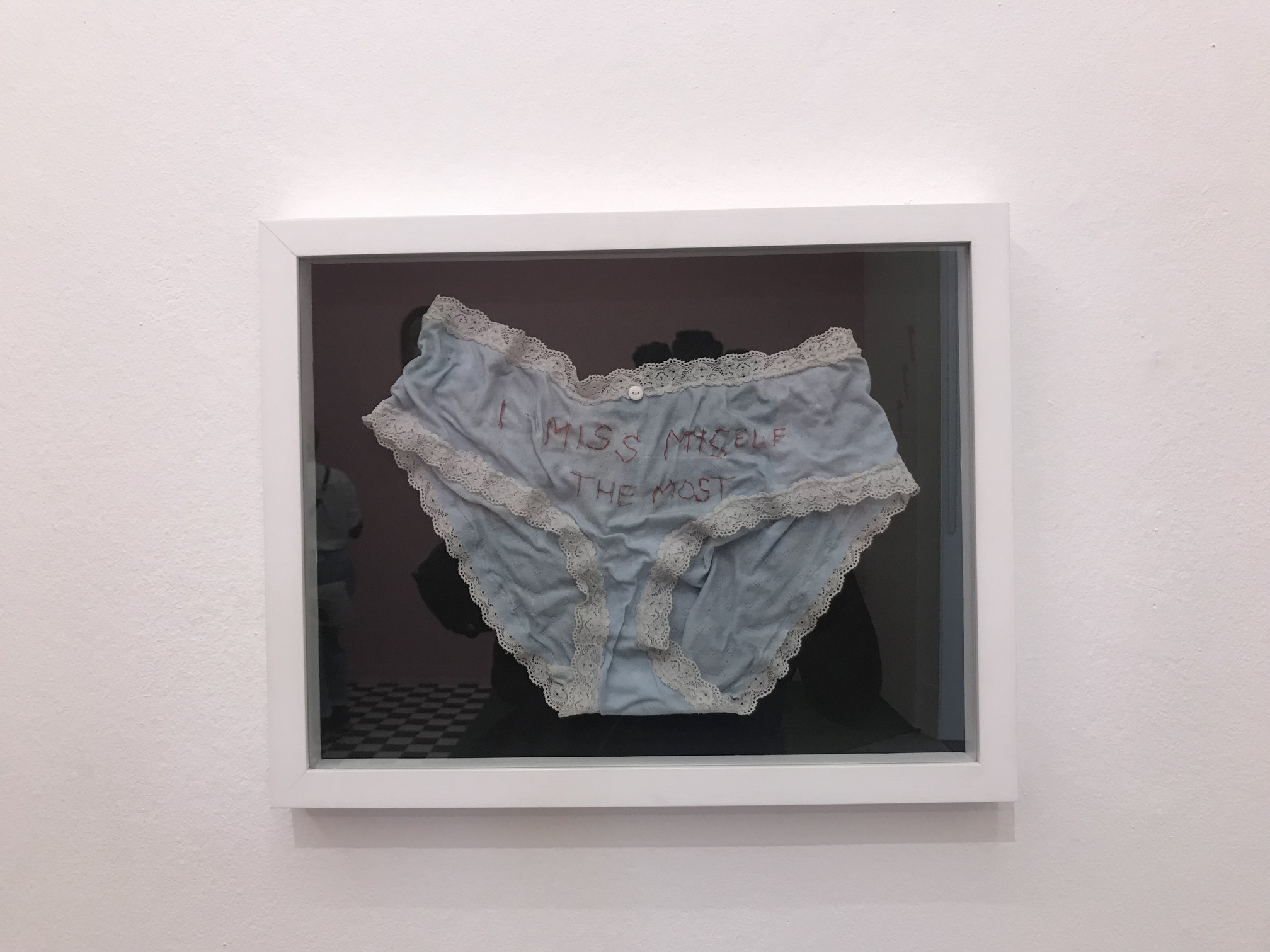

The curators’ guidance through the space played a role in this, almost romantic feeling of safety. It’s as if they themselves were undergoing a gentle exercise of remembering their curatorial process. They spoke softly yet with confident ease about their considerations and introduced each work and artist with professional care. While they named Mahube Diseko‘s I Miss Myself the Most (2023) as the show’s hero piece, the paradoxically modest soft sculpture is eclipsed by Natalie Paneng’s hard intervention, which erects itself on the opposite end of the room, commanding the exhibition’s core.

Ke Thlogo (2023), Paneng’s heady installation, is a surrealist embodiment of memory. It consists of a familiar chair, suspended on the gallery wall, straddling a miniature backyard and its resident pup. Atop the chair is a miniature house with a smartphone video playing through its windows, cable and all. Next to the chair, a room divider with feet, complete with those unmistakable Paneng lips, nose and septum. Its quietly rhythmic elements like portraits, a chandelier, house numbers, pink paint, artificial grass and a checkered floor, connect this bizarre visage to the sticky stuff of our upbringings.

With a BA in Dramatic Arts, Paneng is a self-described “world builder” and it shows in this blatantly triumphant piece. Sat on its floor during her talk at the walkabout, guiding us again in earnest, through her cultural influences and artistic flair, her oral presentation, at least momentarily, blurred the viewers’ perception of the barrier between memory, reality and imagination. She inspired audience questions about worship and spirituality, amplifying the interconnectedness of creation, curation, and making meaning in the physical realm.

In the same room, Lunga Ntila‘s abstract, almost monochromatic, collage portrait, personifies itself in another way. Its form raises existential questions about memory. Smoothly organic cutouts of mirror fragments are imposed on a precarious portrait, projecting the viewer’s own physicality onto that of the artist whose untimely passing at 27 halted a hopeful career.

As they led us to the third and final room, the curators introduced what they termed the “abstraction room,” marked by more visually abstract representations of memory. Two black and white collage pieces adorning the walls on either side of the room from Lebogang Kganye’s series In Search For Memory (2020), had scenes depicting family album silhouettes and furniture from her grandmother’s house, inspired by Muthi Nhlama’s sci-fi tale Ta O’reva (2015), and fixating on personal and national memory.

Mankebe Seakgoe’s calligraphic compositions in paint and sculptural form, work alongside Simnikiwe Buhlungu‘s film The Khuaya (2022). Then again the exhibition meanders back to its fave with Mahube Diseko‘s Travel Safely Back to Your Heart (2022). During the walkabout, Diseko spoke about her transition across artistic mediums comparing her embroidering on underwear to excerpts from an unwritten diary.

There is an undeniable subtlety in that this presentation on memory is predominantly youthful, and this is an advantage heightened by the quietly unjaded sincerity behind the curators’ efforts. Influenced by this innocence, the sweetly nostalgic tone makes I Miss Myself the Most a breath of fresh air in a space like STEVENSON. Rather than returning to established strategies, Mbovane and Molapo have used their novel gaze to seek out work that complicates the viewer’s vision of evocation in a stunningly straightforward, yet speculative way.